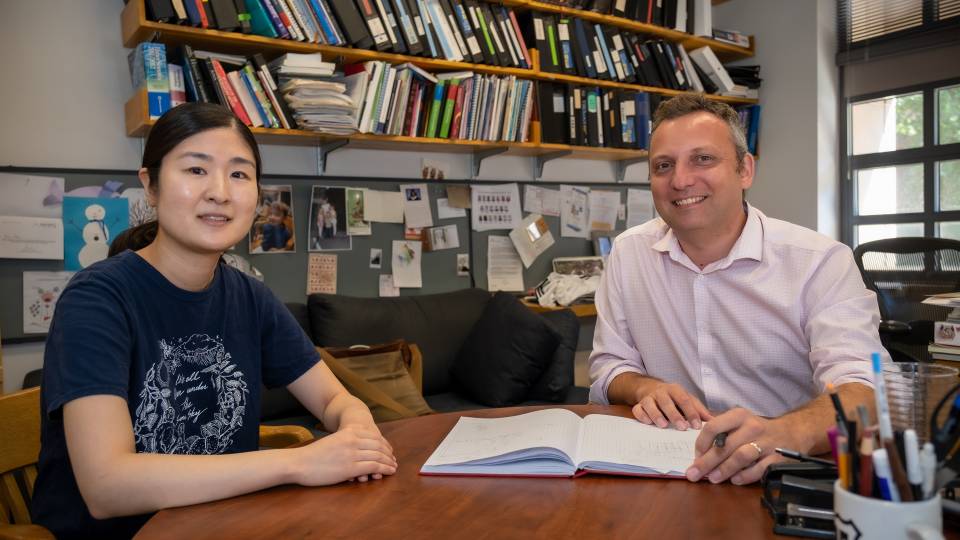

Alin Coman

Princeton researchers have been awarded a National Science Foundation RAPID grant to study how anxiety about COVID-19 influences how we learn and share information about the pandemic.

The NSF's Rapid Response Research (RAPID) program funds proposals that require quick-response research on disasters and unanticipated events.

What the researchers find could help inform the design of campaigns to enhance communication of accurate information and decrease misinformation during times of crisis.

New facts about coronavirus emerge daily, from how infectious it is, to how best to prevent transmission, to which treatments have the greatest chance of success. To keep up with the constant influx of news, people rely not only on the media but on their social networks.

Alin Coman, associate professor of psychology and public affairs, will lead the team.

"The RAPID grant allows us to begin examining the effect of communication on people’s knowledge of COVID-19 as soon as possible," Coman said. "Although there has already been extensive coverage of the pandemic, we are interested in how the already acquired knowledge disseminates through networks of conversational interactions."

Some of the questions the study will address include: Are people who possess accurate information about the virus more or less anxious about the disease? Are people who are very anxious about COVID-19 more likely to spread misinformation to their social network? Are networks in which accurate knowledge transmission is high able to reduce negative emotions? What is the impact of instructing people to be vigilant about misinformation and to correct others’ knowledge during conversations about the community’s acquisition of accurate COVID-19 information?

To address these questions, the researchers will assemble online networks of people who will chat about COVID-19. People will be assigned to one of two network structures having either high or low rates of information transmission. The team will assess the participants’ knowledge of the disease and their level of anxiety about it before and after the conversations take place.

Previous studies by Coman and colleagues have found that people may be more likely to forget important health facts when they are in a state of increased anxiety. Coman and colleagues also found that the structure of a social network affected how similarly people remembered facts following conversational interactions, indicating that people exert influence on one another in what they remember.

"We predict that the high perceived risk of infection should impact information propagation in social networks, and discovering exactly how this occurs should be highly relevant for policies aimed at optimizing accurate knowledge acquisition and propagation," said Coman, who is jointly appointed in the Department of Psychology and the Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs. The researchers also predict that the conversational network structure and the likelihood of members to share accurate or inaccurate information will affect the community-wide knowledge acquisition rate as well as the emotions experienced by individuals.

Funding for this research was provided by NSF under award number 2027225.