The alarming rate at which COVID-19 has killed Black Americans has highlighted the deeply embedded racial disparities in the U.S. health care system.

Princeton researchers now report that low-income Black households also experienced greater job loss, more food and medicine insecurity, and higher indebtedness in the early months of the pandemic compared to white or Latinx low-income households.

Published in the journal Socius, the paper provides the first systematic, descriptive estimates of the early impacts of COVID-19 on low-income Americans. The findings paint a picture of a deepening crisis: between March and mid-June 2020, an increasing number of low-income families reported insecurity. Then they took on more debt to manage their expenses.

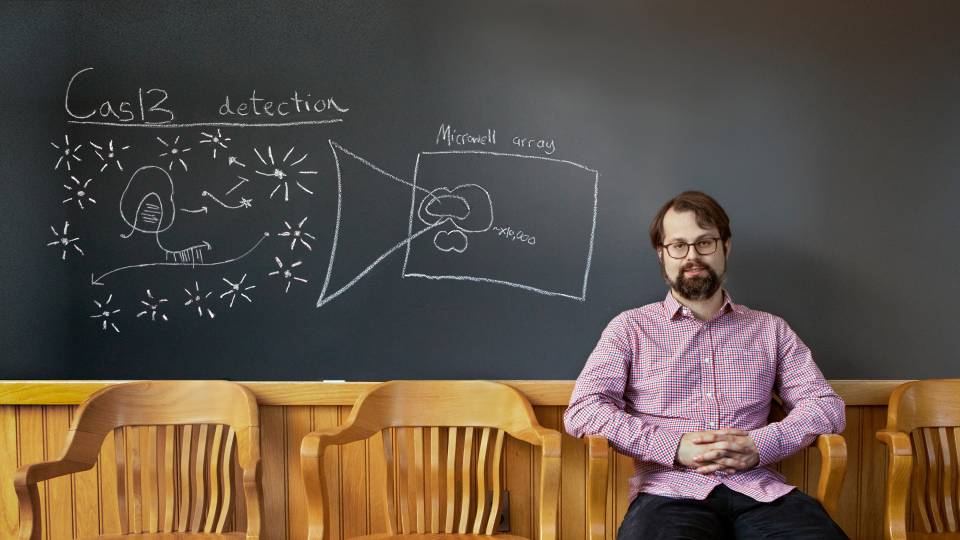

The paper used data from “Fresh EBT,” a budgeting app for families who receive Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) benefits, to provide the first systematic, descriptive estimates of the early impacts of COVID-19 on low-income Americans.

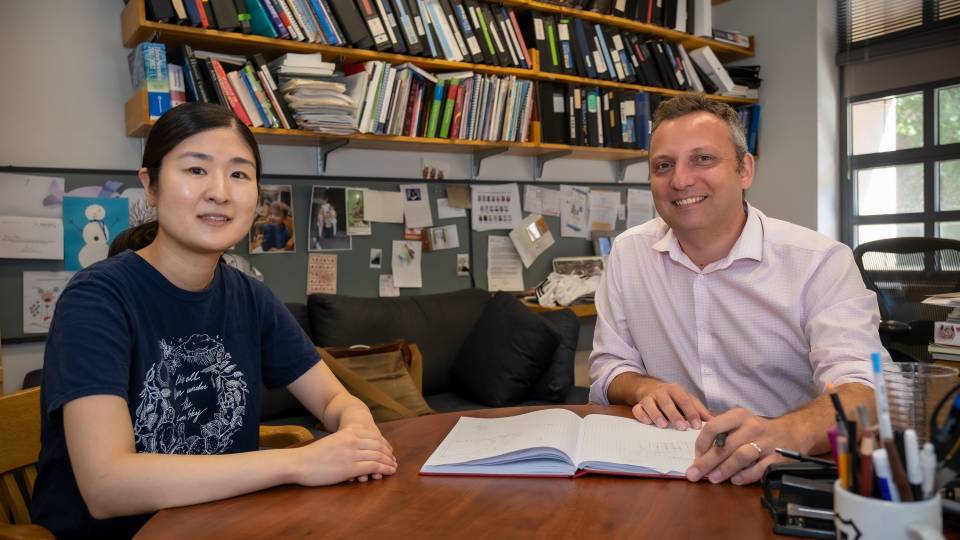

“Media coverage has focused on the racially disparate effects of COVID-19 as a disease, but we were interested in the socioeconomic effects of the virus, and whether it tracked a similar pattern,” said study co-author Adam Goldstein(Link is external), assistant professor of sociology(Link is external) and public affairs at Princeton’s School of Public and International Affairs(Link is external).

It became clear that while all low-income households struggled in the early months of the pandemic, Black households in America were disproportionately affected. “Even among low-income populations, there is a marked racial disparity in people’s vulnerability to this crisis,” said study co-author Diana Enriquez(Link is external), a doctoral candidate in Princeton’s Department of Sociology(Link is external).

Enriquez and Goldstein set out to determine the economic impacts of COVID-19 on Americans of lesser means and the racial disparities within that socioeconomic group. They investigated a set of factors related to families’ ability to satisfy basic needs including job loss, debt, housing instability, and food and medicine insecurity.

The researchers directly surveyed people who utilize the SNAP and Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) benefits. Study participants, who were already low-income and benefits-eligible before COVID-19, were surveyed through between the end of March and mid-June. Goldstein and Enriquez chose this time period because shutdowns were already beginning to affect Americans’ economic livelihoods, but their economic status had not yet been completely transformed.

People were queried about their current and perceived status related to employment, housing, food and medicine accessibility, and debt load. For example, respondents were asked if they had stable housing, and if they believed their housing would be stable after that 30-day period.

They found that people who receive government assistance experienced pronounced effects in all areas except housing. Nearly 35% of all respondents reported losing their jobs by mid-June.

Financial strain and debt accrual also worsened significantly: 67% of people said they skipped paying a bill at the beginning of the shutdown. In each survey wave between the end of April and mid-June, 77% of households reported missing a bill or rent payment. And, despite being covered by SNAP, 54% of people said they skipped meals, relied on family or friends for food, or visited a food pantry due to the COVID-19 shutdown. By the end of the month, this figure rose to 64%.

When the researchers looked at the data by race, it became clear that low-income Black households fared worse than low-income White households on average. Low-income Latinx respondents fared worse than White households on some indicators, but not on others.

At the beginning of the April 2020, 30% of Black respondents reported that they or someone in their household had lost work during the shutdown. By the end of the month, that number increased to 48%. Likewise, 80% of Black households also reported taking on more debt to cover their bills by the end of April. In mid-June, rates of new debt were similar for Black and Latinx households (more than 80%), while approximately 70% of White households reported new debt.

“The survey results really reinforce the extent to which the COVID-19 crisis has kneecapped those households who were already in a tenuous position near the poverty line. Research shows that these types of debts and unpaid bills — even small ones — can compound over time and trap low-income households in a cycle of financial distress,” Goldstein said.

“Even in a miraculous scenario where the pandemic ends in a few months and low-wage workers are rehired, tens of millions of households will still find themselves stuck in a financial hole without additional infusions of economic relief,” he said.

The authors outline the study’s limitations and possible future research avenues. First, the researchers focused on the prevalence of these insecurities, not their severity. They did not measure how many meals were being skipped, for example, or the compounding effects of additional debt. This, as well as other forms of insecurity like access to healthcare or treatment for COVID-19, could be addressed in future work.

The paper, “COVID-19’s Socio-Economic Impact on Low-Income Benefit Recipients: Early Evidence from Tracking Surveys,” was published online at Socius in November 2020.