While Princeton students have just begun the fall semester, their professors have been working for months to reimagine how classes are taught in our new virtual world.

Like schools across the country, Princeton’s undergraduate education is fully remote this fall due to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. In this story, faculty in the sciences, arts, humanities and social sciences talk about how they adapted and innovated their classes for virtual teaching, from science labs and dance classes to introductory lectures and small seminars.

“I’ve been so impressed with how Princeton faculty and staff have worked together on innovative solutions for virtual teaching challenges,” Dean of the College Jill Dolan said. “Although COVID-19 requires inventions born of necessity, our faculty are using technologies to amplify and enliven their typically rigorous and engaging pedagogy.”

As examples, the University shipped laboratory kits to students around the world so they could conduct “at-home” experiments as part of science and engineering courses, and music and arts courses have been transformed so students can still get hands-on, practical experiences.

“We are all learning about remote learning and have worked very hard to bring our students an interesting course about which they can be passionate,” said Dan Notterman, a lecturer with the rank of professor in molecular biology.

Many professors collaborated with the McGraw Center for Teaching and Learning to take existing courses from the classroom to the computer, or to design new classes for virtual instruction. More than 300 professors and instructors participated in 32 virtual academic strategies workshops this summer, and McGraw’s educational technologies staff had nearly 200 consultations with faculty to prepare for fall classes.

“Our faculty are teaching with, not against, the digital tools and online platforms that constitute our new virtual classrooms,” said Kate Stanton, associate dean and director of the McGraw Center. “They are putting the emphasis on creating community — including new forms of community — among students through collaborative assignments and classroom activities.”

Sociology professor Frederick Wherry said he sent McGraw Center staff some ideas for his course “Police Violence, #BlackLivesMatter and the COVID-19 Pandemic” and they ran with it.

“McGraw followed up with a team of people who took different elements of the course and helped me make it better,” said Wherry, the Townsend Martin, Class of 1917 Professor of Sociology. “How to engage. How to collaborate. How to intensify interpersonal connection. They gave me a crash course and followed up.”

As much as the pandemic has separated people, it also has opened new channels of communication and idea-sharing, said Lance Herrington, senior producer and studio manager at the McGraw Center. The University’s Canvas platform, the Princeton Online YouTube Channel and McGraw resources for virtual teaching and learning are among many resources that help make online education easier for faculty and students.

“We’re all collectively learning new tools and working within a different set of limitations than we're used to, but those limitations can actually be a positive thing,” Herrington said. “As instructors, they force us to rethink the optimal ways to communicate our ideas, to design our presentations more thoughtfully and in general offer a more curated experience.”

Below, you can read more about the experiences of the faculty leading the following classes this fall:

- “Police Violence, #BlackLivesMatter and the COVID-19 Pandemic”

- “Classical Sociological Theory”

- “Introduction to Cellular and Molecular Biology”

- “The American Experience and Dance Practices of the African Diaspora”

Police Violence, #BlackLivesMatter, and the COVID-19 Pandemic

Sociology 102, “Police Violence, #BlackLivesMatter, and the COVID-19 Pandemic,” is a new course offered this fall by Frederick Wherry, the Townsend Martin, Class of 1917 Professor of Sociology.

Frederick Wherry

In approaching the McGraw Center, Wherry explained that he wanted a format with a mix of pre-recorded and live lectures. Given the relevance of the topic nationally and the appearance of several guest speakers, Wherry sought out ways to make some of the material accessible to the public, as well.

What is the academic focus of your course?

The course introduces students to the logics and methods of sociology by applying them to the current crises facing America. Using network analysis to see how violence spreads among police officers, experiments to see why #BlackLivesMatter protests are likely (or not) to persuade, and social history to understand what is at stake, we also weave in texts written in the 1800s and early 1900s to demonstrate how early insights from the field’s beginnings can be modified and revived to address today’s pressing questions.

Rather than debate the virtues of both sides of the police violence debate, we will first ask what network analysis tells us about the spread of violence. Just as these techniques have helped police officers predict the violent “hot spots” of gang members, they can also be used by police departments to ferret out which officers are most likely to shoot civilians.

As we look at the #BlackLivesMatter Movement, we’ll ask how researchers have run experiments to determine the conditions that lead audiences watching a #BlackLivesMatter march to react favorably versus unfavorably. When are protestors most likely to persuade, and how do we know? As we introduce students to these techniques and to the logic of sociology as a social science of systematic inquiry, we are able to weave in texts written in the 1800s and early 1900s to demonstrate how those insights from the field’s beginnings can be modified and revived to address pressing questions today.

We’re also starting and ending the class with James Baldwin, who was not a sociologist but who thought like one. We start with “A Report from Occupied Territory” (1966) and end by having a conversation with Professor Eddie Glaude Jr. about his new book “Begin Again: James Baldwin’s American and Lessons for Our Own.” In this way, we ask not just how sociology helps us understand the world, but how we might change it.

What elements of your course are you especially interested in engaging with the students about in this virtual learning environment?

I am most excited about how we have put nearly half of the lectures on the Princeton Online YouTube Channel. People far and wide can follow some of the lectures and conversations with authors. The first batch on police violence is already released onto the channel. Every three weeks, another batch will be released: Part 2, the #BlackLives Matter Movement; Part 3, the Unequal Effects of COVID-19; and Part 4, Back to [James] Baldwin.

I am most excited, though, to see what the students will create as they work in teams to develop multimedia podcasts on the topics covered in this course.

How did working with the McGraw Center help you address a particular challenge as you prepared to teach your course online?

It is hard to know where to begin. I sent along a syllabus and some ideas about how to execute the course. McGraw followed up with a team of people who took different elements of the course and helped me make it better. How to engage. How to collaborate. How to intensify interpersonal connection. They gave me a crash course and followed up.

Embarrassingly, I got myself twisting and turning in all sorts of directions as the term neared. McGraw staff hopped on a Zoom call with me while also being able to directly navigate and make changes to my Canvas site for the course. Even after they more than addressed my concerns, they went the extra step to make sure the semester goes smoothly.

I should add that I received support from the 250th Anniversary Fund for Innovation in Undergraduate Education.

What is one piece of encouragement or advice you would like to convey to students about studying remotely this fall?

Be inspired and inspire others. Yes, consume, but also produce, knowledge. Stay engaged.

Classical Sociological Theory

After teaching an undergraduate sociological theory course last semester, which pivoted to a completely online format in late March, Kim Lane Scheppele came away with insights to innovate her virtual teaching this fall.

Kim Lane Scheppele

“My adaptation was less technical wizardry than emotional outreach,” said Scheppele, the Laurance S. Rockefeller Professor of Sociology and International Affairs and the University Center for Human Values. “My students last term wanted synchronous classes so I kept on more or less as we had been going — though with some technical adaptations to the fact that they were spread out around the world with uneven broadband access.”

For example, Scheppele posted slides for each class that they could play back with just the audio from Zoom if they didn’t have the bandwidth for full Zoom video, which helped one of her students stranded in rural Ireland.

“I added some asynchronous alternative platforms for the students who got sick or overwhelmed and needed to catch up after an absence or who were just too far away to participate in person — and this in particular helped one of my students who wound up in Hong Kong with our class scheduled for the middle of the night her time," she said.

Scheppele also began using an annotation platform to allow students to read in groups, share their reading notes and catch up with precepts missed due to illness or technical difficulties.

“I changed the syllabus in the second half of my course last term — fewer different authors, more pages from each — to help with the general difficulties students were having with concentration," Scheppele said. "But mostly I spent hours and hours and hours in one-on-one meetings, trying to allay their fears and boost their morale.”

This semester, Scheppele is teaching a graduate seminar, “Classical Sociological Theory,” which introduces first-year sociology graduate students the discipline’s canon and history. Below, Scheppele answers a few questions about her plans, and offers some advice for virtual learning.

What elements of your course are you especially interested in engaging with the students about in this virtual learning environment?

The course focuses on difficult texts, so our classes are devoted to figuring out both what these texts said in their own time and also what they say to us now. Discussion is crucial because each person has to “own” these texts for their own future learning. To make discussion more fruitful, I changed our usual once/week three-hour seminar to two one-and-a-half hour meetings instead. I hope that this allows everyone to remain fresh through the discussion.

I’m using the plug-in app Perusall, which allows students to annotate the texts in advance of the class to guide our discussions. This app allows students to see how other students are reading these texts because they can see each other’s annotations. In fact, when I’ve used this in the past, some students have made reading dates so that they read together at the same time — and they can see and respond to each other’s annotation in real time.

How did working with the McGraw Center help you address a particular challenge as you prepared to teach your course online?

I switched to Canvas over the summer, and McGraw helped immensely with that transition. Canvas allows for a cleaner and better organization of course materials, as well as for integrating multimedia teaching materials. In addition, McGraw and OIT approved the use of Perusall within the Canvas platform, which means that students don’t have to search all over to find the relevant course materials. The readings, annotation platform, multimedia links and Zoom links for the classes are all stored within Canvas.

What is one piece of encouragement or advice you would like to convey to students about studying remotely this fall?

Don’t get isolated! Try to find study buddies or other social connections with your fellow students! University education is about more than the classes — you are building friendships and networks for the rest of your life. So work out ways to study with other students. Some of my grad students have organized Zoom dinners together where they meet to talk about what they’ve done during the day. Others have organized Zoom study halls, where students can log in and just see other fellow students studying, as they would if they were in the library or graduate offices together. Still others have organized reading groups to get through difficult course materials together.

Of course, students can also reach out to faculty too — don’t be afraid to sign up for office hours or request a meeting. I enter Zoom rooms early before class and I hang out later after class to schmooze with students as I would if this were an in-person class. We need to find ways to make learning social again, even if we’re all Zooming from home.

Introduction to Cellular and Molecular Biology

“Introduction to Cellular and Molecular Biology” is required for concentrators in molecular biology and ecology and environmental biology. It satisfies the biology requirement for entrance into medical school. This fall, 95 students are enrolled in the course, which includes lectures, precepts and weekly lab reports.

The course is about important concepts and elements of molecular biology, biochemistry, genetics and cell biology are examined in an experimental context. It is being taught by Dan Notterman, Heather Thieringer and Karin McDonald.

Dan Notterman, senior research scholar and lecturer with the rank of professor in molecular biology, said:

“Molecular biology is key to understanding both viral infections such as COVID-19 and the methods used to prevent and treat this disease. We think of MOL 214 as a first step in teaching and producing the next generation of biomedical researchers and clinicians. It is that generation, our students, who will use these molecular tools in a way similar to those who eradicated polio in an earlier time.

“We are all learning about remote learning and have worked very hard to bring our students an interesting course about which they can be passionate.”

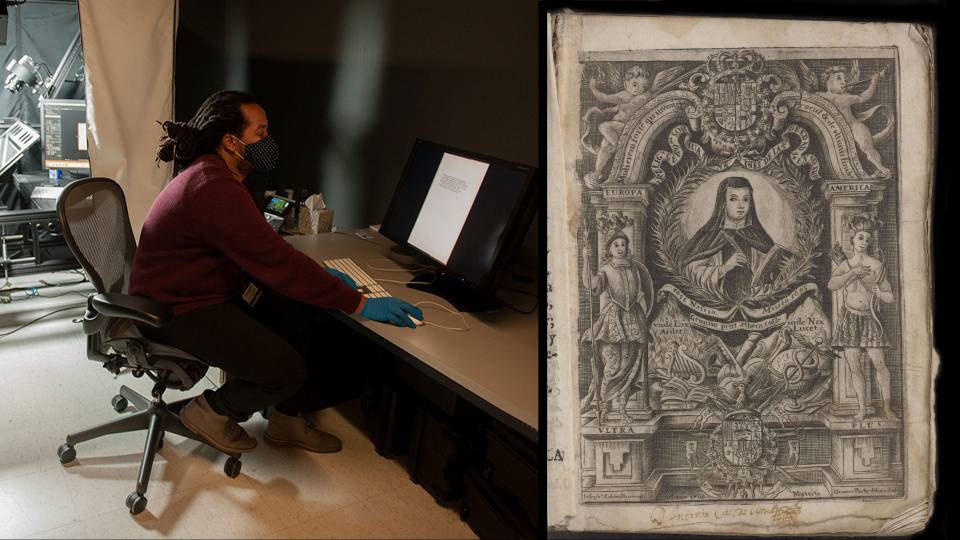

Heather Thieringer, senior lecturer in molecular biology, with science kits ready to be sent to Princeton students for at-home experiments.

Heather Thieringer, senior lecturer, molecular biology said:

"The McGraw Center developed a set of Design Templates which were extremely helpful as we thought about how to teach the lab component of MOL 214. I looked at each lab experiment we normally performed with the students in person and determined what we wanted the students to learn from each one. That helped guide us in how to transform the labs for online instruction. Some labs focus on understanding scientific concepts and data analysis and they transition well to a virtual lab, other labs are more about gaining skills so we developed 'do-at-home' versions of these labs for students to have some hands-on experience. Both the McGraw Center and Environmental Health and Safety were extremely helpful as we went about developing the kits and determining what could easily and safely be done at home.

"It was quite a project to undertake this summer. First we had to test out the actual experiments, to make sure they would work. To factor in shipping time, the lab staff would then leave all the components out at room temperature for four or five days to make sure the experiments would still work. They also were extremely creative is coming up with ways to pack all the components. Development of these MOL kits both for the Freshman Scholars Institute (FSI) earlier this summer and for MOL 214 would not have been possible without the creativity and hard work of the Schultz Teaching Lab staff: Deanne Kennedy, Bettina Wittler and Cara Giordano.

"The FSI MOL mini-course I taught with Dr. Jodi Schottenfeld-Roams for two weeks this summer was a great experience itself, and it also was a good trial run for us for sending kits. There were 18 students in the mini-course (all in the continental U.S.) and we sent kits to the students to allow for a hands-on introduction to the Central Dogma of Molecular Biology and Gene Regulation. MOL 214 has 95 students enrolled including international students so we are certainly scaling up for the fall semester.

"We learned that the students really enjoyed doing the hands-on experiments and gaining skills like micropipetting. Being able to accurately transfer small volumes is essential to most research labs in molecular biology. We will be assessing student experiments via Zoom and asking students to make videos of their results which they will share with their lab section.

"Some component in the kits are to be sent back to Princeton at the end of the course. One thing we learned was to include packing tape in the kit when we send it out — which will make sending it back easier for the students!

"The kits include a micropipette, tips and food coloring along with fun activities that allow them to practice this skill. They also contain all the components necessary to do two experiments that allow students to investigate transcription and translation in a cell-free system. Students will be able to monitor and record the production of RNA and protein using a LED viewer that uses just a 9 volt battery.

"I would love to thank Kate Stanton for her guidance and advice this summer. Also, overall, McGraw ran a bunch of workshops from how to teach on Zoom to how to record videos that were very helpful in getting ready for this semester."

Karin McDonald, lecturer in molecular biology, prepares her home workspace for teaching virtual small-group sessions.

Karin McDonald, lecturer, molecular biology, said:

"I share an office with my daughter who’s entering third grade. I’ll be using a white board for small group work in the MOL 214 precepts. In the classroom, I like to draw things on the board with students during precepts and this has been particularly challenging to replicate with virtual teaching. I’m hoping to overcome this challenge using a physical white board in my Zoom background and an iPad with pencil when drawings and figures are helpful for the course material. The McGraw Center conducted useful workshops over the summer that helped me to implement other teaching tools to increase student engagement, such as Mentimeter and shared Google Docs during breakout rooms. It was extremely useful to experience these training sessions from the perspective of a student.

"During the spring, I regularly hosted Zoom meetings and created breakout rooms for students to work in small groups. I had not, however, experienced breakout rooms as a student. It was useful to see the difficulties students experience on the other side of my meetings. For example, as a host I can send students messages while they are in the room, but I didn’t realize that these messages flash pretty quickly on the screen and then disappear. The McGraw training reinforced how helpful it is to have clear directions with goals in writing at the start of meetings to keep our virtual class on track and everyone onboard with the group work."

The American Experience and Dance Practices of the African Diaspora

This course, cross-listed in the Program in Dance in the Lewis Center for the Arts and the Department of African American Studies, is taught by Dyane Harvey-Salaam, lecturer in dance and the Lewis Center for the Arts. Typically taught as a studio course, it introduces students to American dance aesthetics and practices, with a focus on how its evolution has been influenced by African American and European American choreographers and dancers.

In 2018, students in Harvey-Salaam’s course performed a dance at the dedication of the James Johnson Arch at East Pyne Hall. Johnson was a former enslaved man who worked on campus for more than 60 years until his death in 1902. In 2017, Harvey-Salaam led “Dances of the Diaspora,” a community African dance class with live drum accompaniment, as part of the opening festival weekend of the new Lewis Arts complex.

Dyane Harvey-Salaam in 2018 at the dedication of the James Johnson arch on campus.

What is the focus of your course?

The focus of my course is both practical and theoretical. “The American Experience and Dance practices of the African Diaspora” seeks to provide the physical experience of cultural dance practices while analyzing — through readings, video viewings and guest lecturers — the effect on cultural practices of the United States and the world at large.

What elements of your course are you especially interested in engaging with the students about in this virtual learning environment?

I'd like my students to experience the value of cultural practices, especially those that are different, the value of the arts in our lives, and that a sense of community is absolutely necessary in these troubling times. We are all responsible for each other.

The students are dancing through Zoom, and I have two musicians who play for each class. It is quite an interesting phenomenon. The students are processing movement patterns with a sense of commitment to the form. I am also dividing them into breakout rooms to begin working on movement through group studies.

How did working with the McGraw Center help you address a particular challenge as you prepared to teach your course online?

The McGraw Center introduced me to Canvas and quelled my anxieties about the usage of systems that help organize assignments and other documents. Because I shaped the course around human interaction and physicality, I had made a conscious decision not to use the (online) platforms that were at my disposal. Now I am more comfortable in this process.

For example, (in the past) I chose not to use "discussion board" and "documents/assignment" on Blackboard for submission of assignments, because I was engaging with students in real time, face to face, and collecting/grading hard copies of their papers was my preference. In this new world my preference is obsolete — and learning tools that will make life easier is one of the best paths forward. I'm attempting to use Canvas; however, I do slip from time to time and rely on email.

My approach to using these platforms is centered in engaging students, seeing them and them seeing me, and communication IN REAL TIME with written submissions as assigned. I'm sure this is very different from other applications.

I must give kudos to Adrianna Munson [an instructional designer at the McGraw Center] for a wonderful personal session. I hope to be in contact again as I move forward in the implementation of her suggestions.

What is one piece of encouragement or advice you would like to convey to students about studying remotely this fall?

Do your part to stay connected, remain inspired and passionate about what you DO.

Emily Aronson, Julie Clack, Karin Dienst, Jamie Saxon and Denise Valenti contributed to this story.