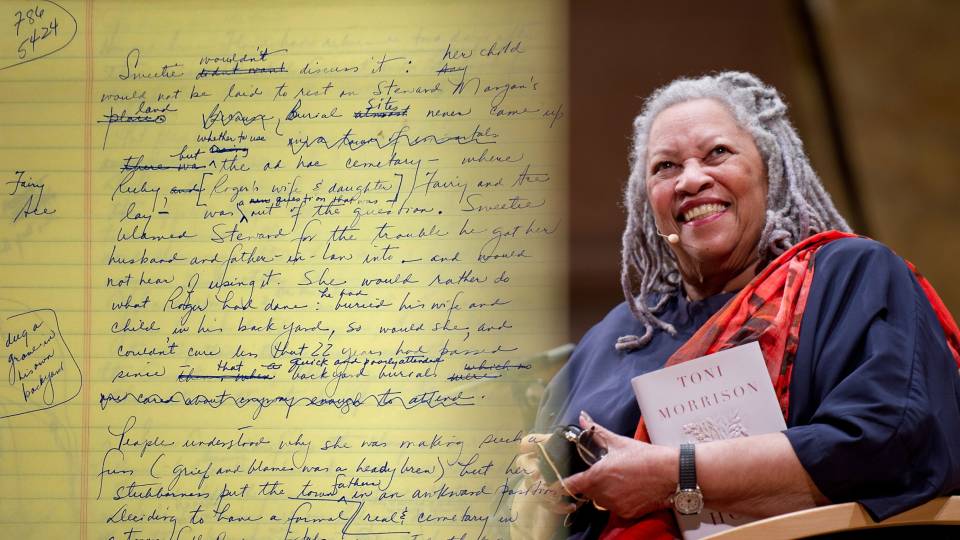

During the coronavirus pandemic, Rhae Lynn Barnes, assistant professor of history, pivoted the content of her “American Cultural History” course and launched an online curriculum to help teachers — inspired by her decade-long research working with racially diverse “Rosie the Riveters,” the subject of her forthcoming book. Pictured: Operating a hand drill at Vultee-Nashville, a woman is working on a "Vengeance" dive bomber, Tennessee.

When Rhae Lynn Barnes designed the syllabus for her spring course “People Get Ready: American Cultural History: 1800-1970,” that hard stop at 1970 was intentional. But the coronavirus pandemic changed her viewpoint in unexpected ways.

“History provides models in courage, innovation and the astonishing human capacity to persevere in moments of crisis,” said Rhae Lynn Barnes.

“I have long used the excuse that historians need adequate distance from historical events to fully understand their implications and significance — which is true,” she said. But when the University transitioned to remote teaching on March 23, Barnes not only pivoted the course content, she also leaned in to her expertise in digital humanities to bring topics to life.

Barnes, an assistant professor of history, also saw an opportunity to help other educators and launched “The Show Must Go On: American Culture in Times of Crisis,” a free curriculum of lesson plans and filmed mini-lectures by leading scholars. Her goal, she said, is to help reduce the workload of millions of teachers and professors on the frontlines of public education during the COVID-19 disruptions.

“History provides models in courage, innovation and the astonishing human capacity to persevere in moments of crisis,” she said.

In this Q&A, Barnes considers how the past is informing her present and how “The Show Must Go On” reflects her commitment to service.

What went through your mind when you learned about the transition to remote learning in February?

Before leaving campus, a student came to my office hours. She saw the gold placard I have on my desk that reads: “What would Beyoncé do?” and said, “I love that!” Having grown up in a sparsely populated area, she found elements of college life hard to adjust to but now considers it a refuge. She wondered how online instruction would work for her when she returned home. It’s my job to make sure that it does.

As she transitioned to virtual teaching, Barnes drew inspiration from her work documenting the experiences of survivors of the Japanese American concentration camps during World War II, including Chiura Obata, a University of California-Berkeley professor who established an art school while imprisoned in Topaz, Utah.

In the digital version of my class, I hope I “post up, flawless” — to channel Beyoncé’s lyrics. But I also ask myself, “What would Chiura Obata do?”

Obata, a UC-Berkeley art professor, was imprisoned in a Japanese American concentration camp in desolate Topaz, Utah, during World II, not far from where my own student is telecommuting from. Appealing to sympathetic donors and the U.S. government, Obata ordered art supplies from a Sears Roebuck catalog. By the time he left Utah, the Topaz Art School he founded while imprisoned served over 600 students. The art they made is on view at the Smithsonian; this link includes a four-minute video about the work.)

Obata engaged in the kind of adaptive teaching in a crisis that the best digital history classes do: democratizing access to information, re-centering marginalized voices, archiving alternative historical perspectives and fighting social isolation.

This is the U.S. history that I want to share with my students. How Americans come together in desperate times. How they can take horrifying realities and unjust obstacles to innovate and put something good into the world that might endure long after we find a cure, long after the vaccination for COVID-19, and long after my students return to campus happy and healthy to celebrate their own golden reunion.

Your course normally ends in 1970. Have you made changes to reflect what’s going on in the present?

After spring break, Barnes added a unit on the 1980s to her course, which typically ends in 1970, to explore the AIDS epidemic “when some of the greatest cultural producers and minds of the 20th century we studied disappeared.” Pictured: The AIDS Memorial Quilt on the Mall in Washington, D.C.

For our online reboot, I started in the 1980s, with the AIDS epidemic — when some of the greatest cultural producers and minds of the 20th century we studied disappeared. We analyzed panels on the AIDS Memorial Quilt. We talked about the musical “Rent.” On the day the NBA shut down in March, I showed them Magic Johnson’s 1991 press conference announcing he was HIV positive. It helped them understand media jokes asking “Is Tom Hanks the new Magic Johnson?” We went to those dark and hard places to understand how and why that pandemic was marginalized or put on the periphery. The global economy did not collapse even though over 30 million human beings died in the AIDS crisis. There are important reasons for that and its implications in the art world were cataclysmic.

How about assignments?

For our first written assignment after spring break, I asked my students to write a journal entry documenting what forms of American culture they were missing (sporting events, dances, graduation, concerts), what happened to them and their families, and what forms of American popular culture they enjoyed while staying home. Their writing was very moving. I asked them to consider letting me donate their memoirs to the University Archives at the end of the semester for future historians to use and understand our own time.

Does “going fully digital” make it harder to present material?

Ironically, going fully digital forces my class into a lower-tech situation because of intellectual property rights law on the digital frontier. It is illegal for me to screen (or “redistribute”) a copyrighted film like “Gone With the Wind” to a class over Zoom to analyze it, so we are focusing on public domain works: the 1915 silent film epic “The Birth of a Nation,” The Farm Security Administration photography during the Great Depression, USO shows.

I also curate weekly interactive multimedia portals — which I do for all of my courses — where students can watch historical footage, and explore galleries of historical images and objects from archives. I curate Spotify playlists of relevant music, podcasts and lectures by the history professors whose books we are reading in class. This is all meant to help them learn in dynamic ways.

Barnes curates weekly interactive multimedia portals where students can watch historical footage, explore galleries of historical images and objects from archives, and listen to relevant music, podcasts and lectures. Pictured: Club DeLisa, Chicago, Illinois

Where did the idea for “The Show Must Go On” come from?

I had many long phone conversations with colleagues who were struggling to convert their classes over spring break. I thought about teachers I know through my work with the Department of Education in New York City — whose students wouldn’t have access to libraries or textbooks.

Barnes’ online curriculum project “The Show Must Go On: American Culture in Times of Crisis” is a free remote teaching resource with lesson plans and filmed mini-lectures by leading scholars. This “Gone with the Wind” poster is featured in the lesson “Protesting Black Stereotypes at the Movies: The Case of ‘Gone with the Wind’ (1939).”

I suddenly had the idea for “The Show Must Go On,” which is just one page of thousands on US History Scene, a remote learning website I founded while in my Ph.D. program at Harvard. I designed it to democratize history education and help with accessible learning for disabled learners. It is also scalable for smartphones — students in inner-city schools and remote areas, who are housing insecure or lack expensive textbooks, still have high cellphone use. Even before COVID-19, the lessons had been used by hundreds of public schools and assigned in university classes globally.

At Princeton, I use it as a digital humanities teaching lab to teach my students how to do digital archival research, storytelling, argument-driven writing and low-stakes coding.

How does it work?

Each lesson plan for “The Show Must Go On” is co-created by incredibly generous colleagues who hop on the phone with me and take 30 minutes out of their day to teach about moments of crisis in American history. Or they create what I call a “selfie-lecture.” For example, I worked with Tera Hunter, the Edwards Professor of American History, and professor of history and African American studies at Princeton, on a lesson plan about the Atlanta Washer Women Strike of 1881.

This is an academic project, but also a service project. What does that mean to you?

I am delighted to learn that it has alleviated strain on tenure track colleagues across the country who are juggling family care and online teaching for the first time. Social studies teachers in New York City have sent moving expressions of gratitude to the many historians who created the lessons. Professors at Georgetown, Harvard, Stanford and UCLA have assigned lessons from “The Show Must Go On” to students.

Historians and educators have also expressed their appreciation. On Twitter, Joe Schmidt at the New York City Department of Education commented on Kevin Boyle’s [the William Smith Mason Professor of American History at Northwestern University] lesson on the photograph of the lynching of Thomas Shipp and Abram Smith on August 7, 1930, in Marion, Indiana. He wrote: “The first three minutes of this 6-minute lecture … models the humanity, honesty and grace required to teach some of the most horrific but necessary content on American racism there is. I recommend every US History teacher take a few minutes to watch this video.”

One of the lessons in “The Show Must Go On” tells the story of the 1932 song “Brother, Can You Spare a Dime?” which became a kind of anthem of the Great Depression.

How does this project reflect Princeton’s informal motto, “In the Nation’s Service and the Service of Humanity”?

Beyond teaching my students at Princeton, one of the greatest honors of my professional career has been working one-on-one for the last decade with racially diverse “Rosie the Riveters” — women who served on the American homefront during World War II building our ships and planes while fighting racial and gender discrimination. Their protest stories are central to my forthcoming book “Darkology: When the American Dream Wore Blackface.” The history lessons they’ve imparted to me align with Princeton University’s ideals: that we have a social responsibility to use our talents to serve others, that we can do tremendous things together, that we must protect anyone facing discrimination, and that in times of crisis it is our duty as American citizens to serve our country and fellow humanity.