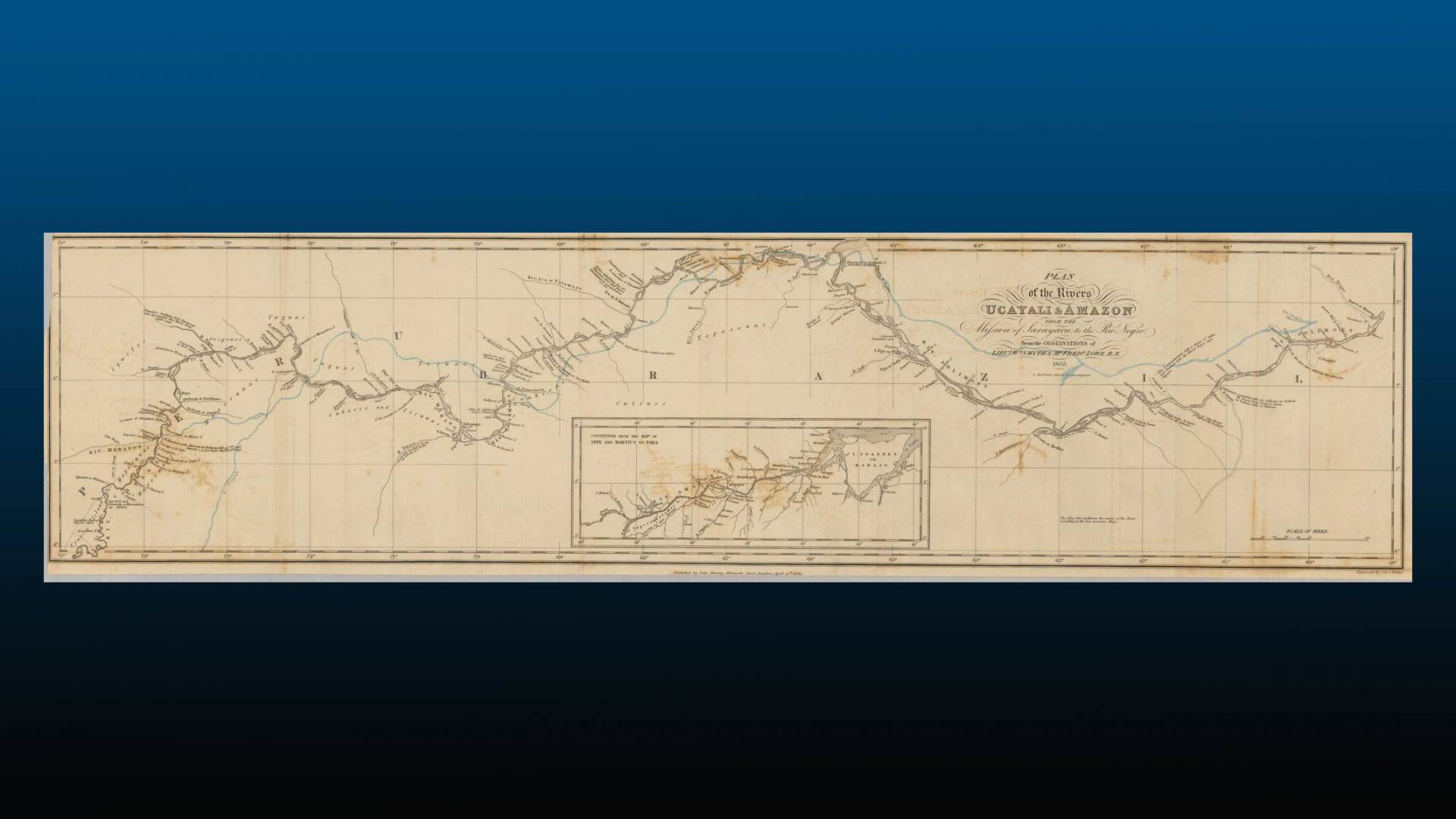

The spring course “Amazonia, The Last Frontier: History, Culture, and Power” transitioned to remote instruction after spring break due to the coronavirus pandemic. Earlier in the term, students had visited the Princeton University Library’s Special Collections to see several rare and unique items on the Amazon, and then, from off-site, they were able to access the materials digitally. Shown: Plan of the rivers Ucayali & Amazon from the Mission of Sarayacu to the Rio Negro from the observations of Lieut. Wm. Smyth & Mr. Fredk. Lowe, R.N., 1835.

The spring course “Amazonia, The Last Frontier: History, Culture, and Power” transitioned to remote instruction after spring break due to the coronavirus pandemic. Earlier in the term, students had visited the Princeton University Library’s Special Collections to see several rare and unique items on the Amazon, and then, from off-site, they were able to access the materials digitally.

“Princeton has an incredible collection of rare books, maps and photographs on the Amazon, from colonial times to more recent American enterprises in the region,” said Miqueias Mugge, an associate research scholar and lecturer at the Princeton Institute for International and Regional Studies (PIIRS). “Our online transition went smoothly as the Library expeditiously made all the materials available in digital format,” Mugge said.

“Princeton has an incredible collection of rare books, maps and photographs on the Amazon, from colonial times to more recent American enterprises in the region,” said Miques Mugge, an associate research scholar and lecturer at the Princeton Institute for International and Regional Studies. Shown: Building the Madeira-Mamoré Railroad.

Offered by PIIRS’ Brazil LAB and the Program in Latin American Studies, the seminar examined projects to colonize, develop and conserve the Amazon over time, and was centered around multiple visits to Firestone Library to to examine items in the special collections, including prints, maps and rare books. The visits were organized by Fernando Acosta-Rodriguez, the librarian for Latin American studies, Latino studies and Iberian Peninsular studies.

Zoom and videoconference services allowed Mugge to preserve another key facet of the class: the participation of Brazilian guest lecturers, including historian and anthropologist Lilia Moritz Schwarcz, professor at the University of São Paulo and visiting professor of Spanish and Portuguese at Princeton, and anthropologist Maria Virginia Amaral, trained at the Brazil’s Museu Nacional in Rio de Janeiro. Both Schwarcz and Amaral are scholars affiliated with the Brazil LAB and are part of the LAB’s research hubs.

“Students loved engaging with the archival research and ethnographic fieldwork of these remarkable scholars and learned much about pressing issues that indigenous peoples are facing right now,” Mugge said. Deeply committed to the course’s continuity in unnerving times, he more purposely interspersed lecture with time for debates. “This made the course ever more dialogical, critical for community building at a distance.”

“This class has translated pretty well to an online format,” said Alice Wistar, a senior who is currently in Philadelphia. “We have still been able to have guest speakers Zoom in from Brazil.” Wistar is a Spanish and Portuguese concentrator and is earning certificates in global health and health policy and Latin American studies. “We haven’t missed out on much,” she added.

Alex Giannattasio, a sophomore who is participating in the class from Washington, D.C., said: “We are still able to have guest speakers, we do group breakouts, we watch videos together in lecture. We have a good sense of community, and I don’t think that has faltered since going online. A lot of us are from different [academic] backgrounds, which brings a rich dynamic to the class.” Giannattasio has declared a concentration in the Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs, and is considering earning certificates in environmental studies, Latin American studies and sustainable energy.

Undergraduate students (from left) Keely Toledo, Joseph DiMarino, Jimin Kang and Alexander Krauel study materials in the Princeton University Library Special Collections before the start of remote instruction due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Teaching during the coronavirus crisis

Wistar, who has interests in environmental studies and behavioral science and is writing her senior thesis on meat consumption, felt very engaged with current events in the April 16 meeting, which discussed cattle, soy and deforestation. “The system that we currently have in place that puts profit over anything else is clearly not working,” said Wistar. “The conditions of livestock are breeding grounds for zoonotic pathogens. Who’s to say this couldn’t happen again because of how we are treating agriculture and food systems?”

The pandemic has also allowed Mugge to stress the course’s paramount takeaways: that the world’s largest tropical forest is the ancestral home of over one million indigenous peoples and that it is imperative to draw from the cultural wisdoms of its guardians, as we seek to develop visions to safeguard the forest for Brazil and the planet.

“Throughout the course, we studied how pandemics affected indigenous peoples in the Amazon since the 16th century,” Mugge said. “COVID-19 is a radical threat for indigenous peoples now, mirroring both the violence of predatory invaders that they have been struggling with for centuries and the current precariousness of public health systems in the region.” Deforestation also can result in the emergence of new diseases, Mugge said, noting that “over two hundred arboviruses have been already identified by Amazonian scientists, and further forest degradation can cause new viral cross overs and potential harmful outbreaks.”

When the Amazonia course met for the final time on April 30, the class decided to build a website to share their independent research projects — an activity that was not on the original syllabus. Most students are developing podcasts, exhibitions of visual materials and short essays. Others are producing educational videos. The site will be launched this month.

Miqueias Mugge, top left, meets the class over video.