From their laptops, scattered around the world, students in the spring course “Literature and Medicine” discover that literary texts keep them connected to one another — and help them grapple with their own experiences during the pandemic. Pictured: Junior Charlotte Adamo (left), London; sophomore Jason Hong, Rockville, Maryland; and junior Kiersten Rasberry, Aurora, Illinois.

Weeks before the coronavirus crisis hit, the 99 Princeton undergraduates in the spring course “Literature and Medicine” were already immersed in the many ways storytelling shapes the way we understand and experience illness, disease and health. Now, from their laptops, scattered around the world, the students are discovering that literary texts are not only keeping them connected to one another, but also helping them grapple with their own experiences during the pandemic.

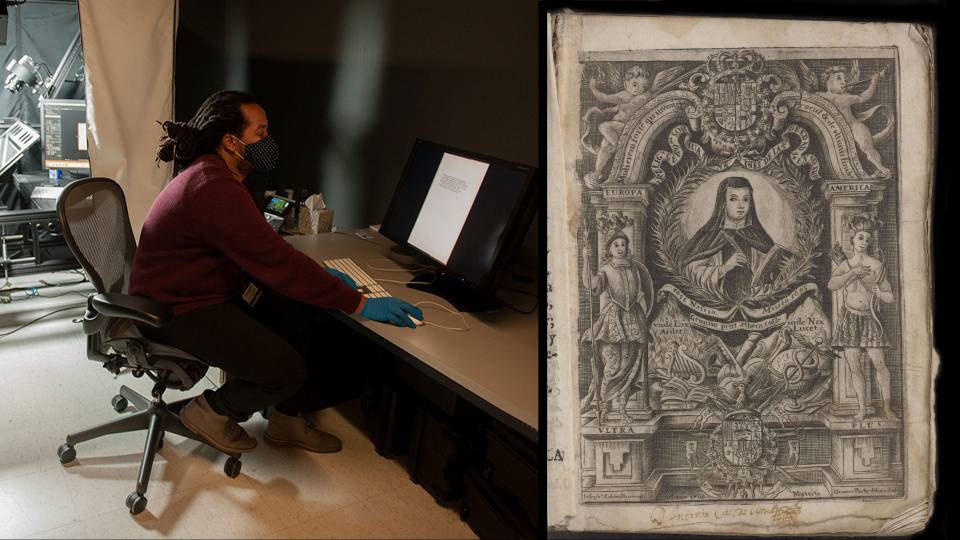

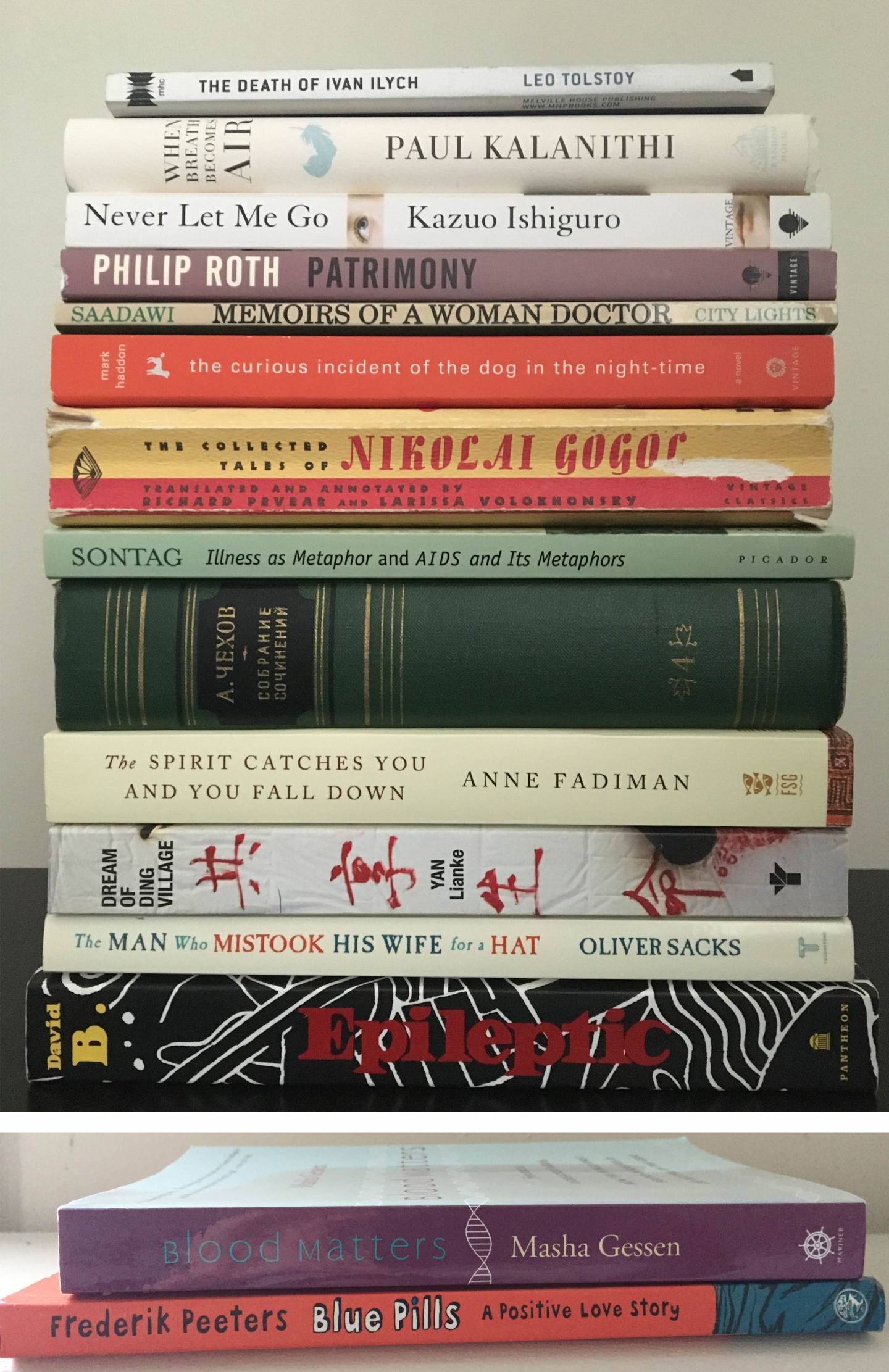

Students are exploring texts across genres, centuries and the world. The books (top) are from the desk of Elena Fratto, assistant professor of Slavic languages and literatures, who is teaching the course remotely from the Boston area; the books (bottom) are from the desk of Jacob Plagmann, a graduate student in comparative literature and one of three assistant instructors who lead online precepts with the 99 students.

“As you can imagine, my students, most of whom intend to go to medical school, have a lot of things to say,” said Elena Fratto, assistant professor of Slavic languages and literatures. “Some of them have been personally affected by COVID-19, some have experienced family loss. They share valuable insights on the role of the humanities in this historical moment.”

Fratto said she adapted the syllabus, class discussions and assignments in several ways to bring the pandemic into focus. For example, she made the unit on epidemics more robust; beyond literary perspectives on the AIDS epidemic in the 1980s in the U.S., students also delved into classic readings on epidemics “as signifiers of a culture and its deep-seated values and fears — from [American historians of medicine] Charles Rosenberg to Frank Snowden,” Fratto said.

One discussion was about the tendency to pathologize a place along with its population and culture. Just as COVID-19, despite being a world-scale pandemic, is still referred to as “the Chinese virus” or “the Wuhan flu,” Fratto said, her lectures explored similar kinds of scapegoating in public health campaigns on AIDS; works by 19th-century Italian author Alessandro Manzoni — who wrote about the 17th-century bubonic plague, allegedly caused by people called untori, sent by the devil to grease the frames of people’s doors with the infection — and Italian Renaissance physician-author Girolamo Fracastoro, who defined syphilis as “the French disease”; and the mysterious “Asian fever” that threatens Russia at the end of Dostoevsky’s “Crime and Punishment.”

During online class sessions and precepts, Fratto and her three assistant instructors — graduate students Jacob Plagmann (comparative literature), Gabriella Ferrari (Slavic languages and literatures) and Liza Mankovskaia (Slavic languages and literatures) — have encouraged “free-form discussion on what our societies are experiencing and how we can read and approach these events through the lens of literature,” she said. “Literary works are works of art. Storytelling and plot-construction are tools that individuals and societies employ to make sense of illness and health, to build meaningful totalities out of scattered events and phenomena.”

Students are exploring texts across genres, centuries and the world — from Chekhov’s, William Carlos Williams’ and Nawal El Saadawi’s autobiographical “doctor stories” to Yan Lianke’s 2006 novel “Dream of Ding Village,” based on a real-life blood-selling scandal in contemporary China; from Gogol’s and Lu Xun’s “madmen’s diaries” to Kazuo Ishiguro’s 2005 dystopic novel “Never Let Me Go”; from British neurologist-author Oliver Sacks’ clinical tales to Anne Fadiman’s 1997 “The Spirit Catches You and You Fall Down: A Hmong Child, Her American Doctors and the Collision of Two Cultures.”

More readings are captured in the reflections below, in which some of the students describe how a concept or literary work from the course has helped them navigate their own experience or understanding of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Charlotte Adamo, a member of the Class of 2021, reviews her work at home in London as her cat Sylvia proofreads.

Charlotte Adamo, Class of 2021

Ecology and evolutionary biology concentrator; London, UK

With our imagined return to “normal” life retreating further and further into the future, we’re left uncertain, floating in the present’s rarefied air. The peculiar nature of the current circumstances has altered my relationship with time, and I’ve found myself turning to narrative theory and concepts of plot to give meaning to my own isolation. As a result, reflecting on the “now” as a part of a coherent whole provides me with a sense of continuity and direction, providing mindfulness in seemingly mundane daily experiences, rather than letting them blur into a haze of disconnected images, bobbing in my temporal sea.

Jason Hong, a member of the Class of 2022, takes notes at home in Rockville, Maryland.

Jason Hong, Class of 2022

Molecular biology concentrator; pre-med; Rockville, Maryland

What bothered me the most while reading Tolstoy’s “The Death of Ivan Ilych” wasn’t the physician’s inability to diagnose Ivan’s mysterious disease. It was rather the complete apathy displayed by his friends and family that made me sympathize for Ivan, who was left to suffer by himself. Reflecting back on this story has made me realize that overcoming a novel illness such as COVID-19 cannot be done alone. This pandemic requires everyone, whether infected or not, to be fully committed in keeping transmission to a minimum. Ivan may have died alone, but we will defeat this pandemic together.

Daniel Kwak, Class of 2021

Psychology concentrator, pre-med; North Hollywood, California

[Physician] Paul Kalanithi’s battle with his cancer in [his memoir] “When Breath Becomes Air” is a testimony to the harsh fact that sometimes, life is a dark tunnel that stretches on endlessly. Every step seems to only lead to a new wave of uncertainty and fear. However, Kalanithi’s unfaltering drive for a meaningful life in the face of death carries an encouraging message to be steadfast in the midst of today’s pandemic-struck society. He inspires me to continue to demonstrate love and empathy towards one another in such unpredictable and difficult times. After all, at the end of every dark tunnel, there’s light.

Leah Linfield, Class of 2021

English concentrator, pre-med; Dorset, Vermont

“Blue Pills: A Positive Love Story” is a graphic memoir by Swiss artist Frederick Peeters. It traces Peeters’ relationship with Cati, a single mother who is HIV-positive. In a pandemic or epidemic, it is all too easy to focus on numbers — death rates, statistical models and rates of resource depletion. It’s harder to hear the stories behind those numbers — stories of grandparents waving to their grandchildren through a window or of doctors having to choose which patients get to live. Literature, like Peeters’ memoir, reminds us that people are not numbers. We must always choose to listen to their stories.

Chy Murali, Class of 2022

Molecular biology concentrator; Burtonsville, Maryland

As I witness the alienation that many Asian Americans are currently experiencing due to the xenophobic rhetoric surrounding this supposedly “Chinese virus,” I cannot help but feel constantly reminded of Susan Sontag’s words in “Illness as Metaphor” that “nothing is more punitive than to give a disease a meaning ...” I now understand the pitfalls she cautioned us against falling victim to by allowing a disease of foreign origin to become something that individuals can exploit to exacerbate irrational, racist fears. Her words have prevented me from viewing the virus as anything more than a biological entity and hurting those whose identity is in no way tied to it.

Kiersten Rasberry, a member of the Class of 2021, reviews an online gallery of artworks from the Princeton University Art Museum created for the course by Veronica White, curator of academic programs. "The image on my laptop is a screenprint from David Wojnarowicz and James Romberger's '7 Miles a Second,' depicting the horrific, yet intimate nature of AIDS, and its role in impacting not only the life of the patient, but their social network, as well," Rasberry said from Aurora, Illinois. Prior to the transition to remote instruction, the class visited the museum to study works related to medicine, illness and health from the collections and the special exhibition "States of Health: Visualizing Illness and Healing."

Kiersten Rasberry, Class of 2021

Anthropology concentrator, pre-med; Aurora, Illinois

I’m constantly thinking about COVID-19’s impact on local and global communities. David B.’s graphic novel “Epileptic” has become an important text in helping me conceptualize the discourse surrounding COVID-19. The stigma encompassing Jean-Christophe’s disease is reflective of the idea of illness as taboo. Time and time again I have witnessed people’s coughs accompanied by stares, as well as individuals referring to COVID-19 as “It” to distance themselves from the “invisible enemy.” With this new pandemic comes old metaphors and the stigmatizing ideals associated with them.