A Princeton course examines ancient engineering techniques and how they relate to modern engineering innovation. Pictured: Students in a fall break trip visit the Parthenon in Athens listen as Vasileia Manidaki (center), architect of the Acropolis Restoration Service, describes the ancient system for aligning column drums with wooden centering pins.

The ingenuity of the construction techniques used by Greek builders 2,000 years ago continues to dazzle the world. What did these ancient engineers get right? And how does looking to the past help current engineering students become bolder and more creative in their own work?

To give civil and environmental engineering students an immersive experience in ancient engineering techniques and how they relate to modern engineering innovation, two Princeton professors devised the course “Historical Structures: Ancient Architecture's Materials, Construction and Engineering.” One instructor brings the perspective of an engineer, the other is steeped in humanities scholarship.

Branko Glišić, professor of civil and environmental engineering, hopes students will take inspiration from the curiosity, creativity and experimentation of the ancient Greeks, among other cultures. “The Greeks’ mixture of playfulness and discipline showed excellent results some 2,000 years before the scientific concepts even started to be developed,” he said. “Understanding the evolution of engineering thoughts and experiences helps build the intuition, creativity and confidence necessary to push the boundaries of the discipline.”

His co-instructor, Sam Holzman, assistant professor of art and archaeology and the Stanley J. Seeger '52 Center for Hellenic Studies, sees the class as an opportunity "to look for the ways that the humanities and the applied sciences inform one another.”

“I hope we are training bright young people to have a lifelong openness to collaborate across disciplines," Holzman said.

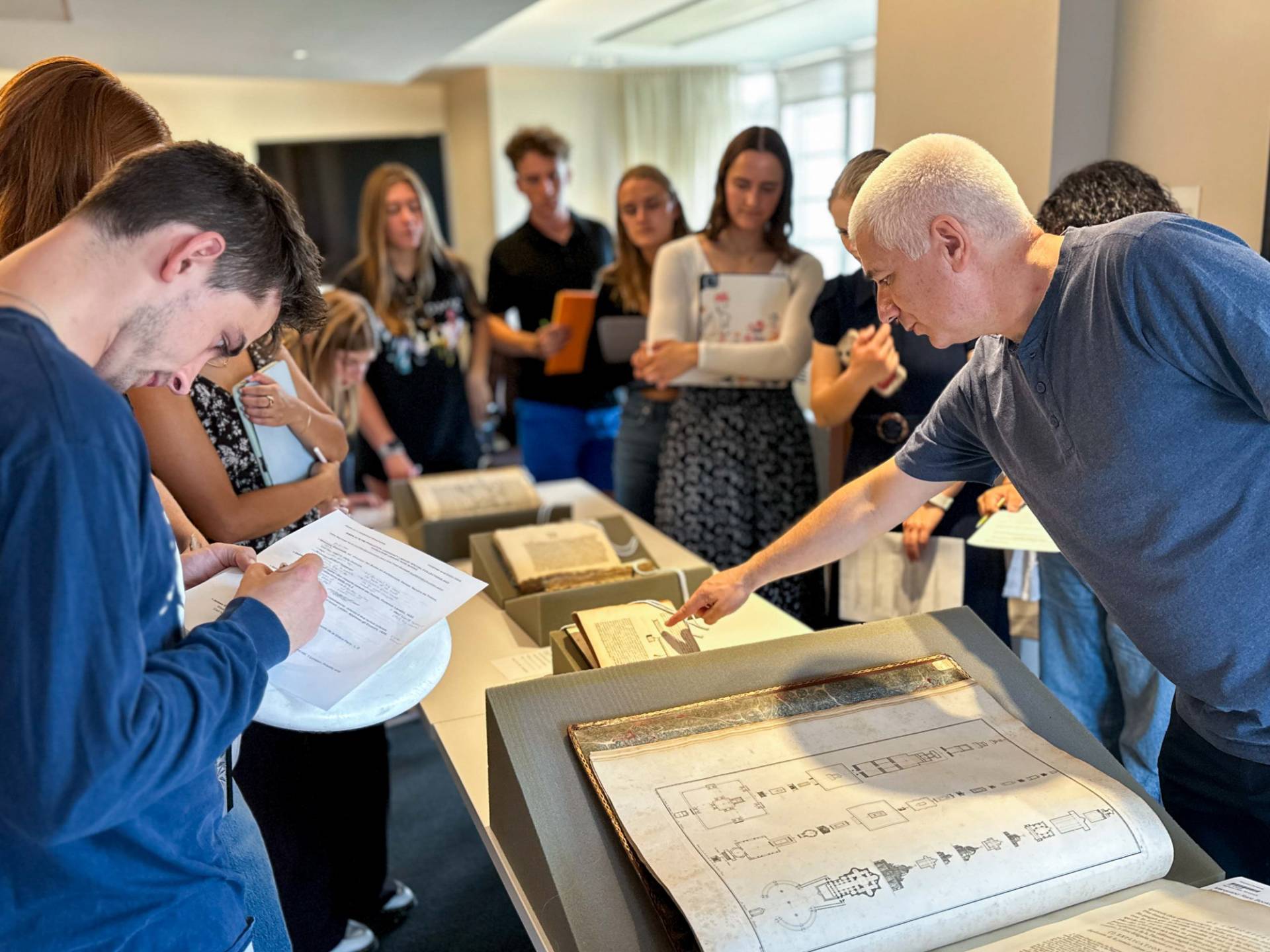

Branko Glišić points to a page on cantilevers in Galileo Galilei’s “Two New Sciences,” published in 1638, at Princeton University Library's Special Collections.

The course is cross-listed in the Program in Humanistic Studies, art and archaeology, civil and environmental engineering, and Hellenic studies. It is open to all students, including those majoring in engineering and a range of humanities and social science disciplines. It was supported by Magic and Team Teaching grants from the Humanities Council, a grant from the Council on Science and Technology, and by the departments of civil and environmental engineering, and art and archaeology.

Glišić and Holzman regularly collaborate on their research and don’t see a definitive border dividing their respective disciplines. They call their course an interdisciplinary “mashup.” And the elaborate schematics they draw together on the whiteboard during each class session combine Holzman’s architectural sketches and Glišić’s equations and engineering drawings — each dynamically informing the other.

Sleuthing out clues from the past

During fall break, 15 Princeton students traveled to Greece to examine ancient Greek architecture up close and immerse the students in the culture of ancient Greece and how that shaped architectural aesthetics.

At one stop in Athens, the ancient Roman Agora, the students examined a cluster of stone blocks embedded in a wall. The blocks had been carefully shaped to function as a chain of cantilevered and suspended beams. Most visitors walk right by them. Holzman told the students that this was a precursor in stone to the Gerber beam system used by today’s engineers, then Glišić expanded on the engineering principles at play.

Thanks to Holzman’s and Glišić’s relationships with colleagues in Greece, including the Greek Ministry of Culture, the class had the exceptional opportunity to study ancient structures, including some dating as far back as the second millennium B.C.E.

On the Acropolis in Athens, for example, students were thrilled to be allowed to cross the visitors’ ropes and see the Temple of Athena Nike — and outright awestruck when Glišić and Holzman lifted the hatch to descend into the temple’s foundations.

At the Greek Agora, stepping into the Temple of Hephaistos prompted a prime example of the interdisciplinary detective work central to the course, when Glišić observed a crack above a doorway. After Holzman explained that the door was added when the temple was converted to a church, Glišić helped students analyze the resulting spiderweb of cracks.

“Branko can sleuth out a whole cascade of clues that explain what happens to a building over time,” said Holzman. “Seeing a building through the eyes of a world-renowned expert in structural health monitoring like Branko makes students aware of the extreme stresses that buildings are under and the many imperceptibly small ways that building materials compress, bend and vibrate.”

Glišić enjoys team-teaching with Holzman, who provides the art historical context at each site. “Engineering questions suddenly found logical solutions, as Sam provided the missing pieces that fell into place like mosaic tesserae and completed the picture.”

Learning from experts — including Galileo

Students also learned from a host of experts, both in Greece and at Princeton. Vasileia Manidaki, architect of the Acropolis Restoration Service, led a visit to the Parthenon and a nearby workshop where marble experts were using ancient techniques to carve stone for reconstruction. At the Temple of Zeus at Nemea, 70 miles west in the Peloponnese, students met with Nicos Makris, the Addy Family Centennial Professor in Civil Engineering and professor of civil and environmental engineering at Southern Methodist University, who was working on a reconstruction project there.

Ellen Toberman ’25 and co-instructor Branko Glišić (foreground), professor of civil and environmental engineering, trace a pattern of cracks in a wall of the Temple of Hephaistos in Athens.

Holzman said it is important for students to meet these “civil engineers, architects, archaeologists and marble carvers who are experts in ancient building techniques.” These visits underscore “the importance of the interdisciplinary interchange at the heart of this course,” he said.

On campus, the class visited Princeton University Library’s Special Collections to trace 500 years of ancient structures through the library’s rare books collection. Among the highlights was Galileo Galilei’s “Two New Sciences,” published in 1638, in which he set out the first analytical approach to cantilevers.

Behind Green Hall, the class also tried their hand at marble carving, gaining hands-on insight into the difficult art they had witnessed on the Acropolis just weeks before.

Looking at engineering solutions ‘in the context of history, community and humanity’

“In my other CEE courses, the focus is typically on the latest, most technologically advanced techniques in the field,” said Ellen Toberman ’25, a civil engineering major. “This class delved not only into the physics that allow historic structures to endure, but also into the construction processes and the ingenious tools employed by ancient builders. It was a fascinating shift that broadened my appreciation for the ingenuity of the past.”

Toberman said the historical context the course provided has shifted her outlook. “The ancient structures that we studied were not only feats of engineering but also expressions of cultural identity, resilience and purpose. This perspective has encouraged me to approach engineering problems with a more holistic mindset, considering not just the technical aspects of a project but also its broader context and impact.”

Civil engineering major Braeden Carroll ’26 said the course helped him think about how his technical education interacts with the humanities in meaningful ways. “As I go forward with my engineering design courses and whatever the world beyond holds in store, I will do so remembering to think about problems and solutions in the context of history, community and humanity.”

Comparative literature major Lucia Brown ’25 agreed. “The combination of disciplines in this course offers the perfect example of why understanding the relationship between engineering and the humanities is so critical,” she said.