Many engineering lectures concern themselves with cutting-edge technology but at a recent talk on bridge construction, Princeton professor Branko Glišić(Link is external) asked his audience to go back nearly 2,000 years.

“You have to think like a Roman,” Glišić told students and faculty gathered for a brown-bag lunch. He gestured to a schematic diagram of an arch on the screen behind him. “You have to do something simple; so you minimize connections because they add complication.”

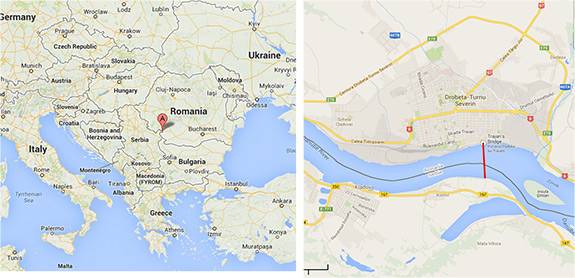

Glišić, an assistant professor of civil and environmental engineering(Link is external), was speaking about Trajan’s Bridge, a wood-and-masonry structure that the Romans constructed between 103 and 105 A.D. to span the Danube River between what is now Serbia and Romania. At more than a kilometer long (six-tenths of a mile), it is considered a wonder of the ancient world, but nearly all details of its form and construction were lost and it is unclear how long it stood. Glišić and former Princeton undergraduate Anjali Mehrotra have reconstructed the engineering behind the bridge and published their findings in the Journal of Cultural Heritage.

Researchers led by Branko Glišić, an assistant professor of civil and environmental engineering at Princeton, used modern engineering analysis to determine the materials and techniques that ancient Roman engineers used to build Trajan’s Bridge over the Danube River. (Photo by Frank Wojciechowski for the Office of Engineering Communications)

Glišić and Mehrotra used modern engineering analysis, coupled with a review of available materials and historic records of Roman construction techniques, to draw their conclusions, some of which run counter to historical assumptions. Mehrotra majored in civil and environmental engineering and graduated last year.

Glišić said the inspiration for the work came two years ago when Mehrotra expressed interest in pursuing research involving art and history, and Glišić suggested Trajan’s Bridge. A history buff, Glišić walked around the eroded bridge pillars during his childhood in Serbia and wondered what the bridge had looked like.

“I remembered the bridge and I was thinking how difficult it would have been to build it at that time,” he said.

A carving from Trajan’s Column in Rome (at left and upper right) and a contemporary Roman coin provided clues to the bridge’s form. (Images courtesy of Branko Glišić)

Built under the Emperor Trajan, the bridge has inspired wonder for centuries.

“Trajan constructed over the Ister (Danube) a stone bridge for which I cannot sufficiently admire him,” the Roman consul and historian Cassius Dio wrote a century later. “Brilliant, indeed, as are his other achievements, yet this surpasses them.”

Even by the time Cassius Dio wrote his words, however, the bridge’s actual form had faded from memory — except for the bridge piers, the structure was made of wood, not stone as Dio states.

For Mehrotra, that mystery was compelling.

“I’ve always had an interest in history, so the opportunity to combine history and engineering really appealed to me,” Mehrotra said. “In fact, I enjoyed it so much that I went on to do my senior thesis on the Taj Mahal.” Next year, Mehrotra willl begin graduate research at the University of Cambridge on seismic retrofits for heritage structures.

For the Romans, the bridge was both functional and symbolic. Matthew McCarty, an archaeologist and a fellow in the Princeton Society of Fellows in the Liberal Arts, said Trajan built the bridge to support an invasion of the neighboring kingdom of Dacia, now part of modern-day Romania and Serbia. McCarty, who specializes in Roman history and is excavating the site of a Roman settlement in Dacia, said the invasion could have been carried out using boats, but a bridge would show the Roman’s technological power.

“Imperial authority could be demonstrated,” he said. “Bridging a vast river would send a message — not only can we conquer a people but we can conquer all natural physical boundaries as well.”

The researchers reviewed a number of historic representations of the bridge that were proposed by scientists over the past two centuries, but rejected all or elements of various analyses either because of instability issues or the use of techniques that the Romans were unlikely to have mastered, such as fixed joints.

They relied heavily on the representation made on Trajan’s Column in Rome, which was a contemporaneous representation built to commemorate the highlights of the emperor’s rule. The relatively small scale of the carving on the column, however, makes it hard to discern details, Glišić said.

The bridge’s designer, Apollodorus of Damascus, wrote his own account of the construction. “Unfortunately, the book has been lost,” Glišić said.

The bridge spanned more than a kilometer of the Danube in the Iron Gates region between modern-day Serbia and Romania. (Maps courtesy of Branko Glišić)

Adding to the quandary, the design depicted on Trajan’s Column proved to be unstable when the researchers analyzed the stress at the bottom ends of each arch. The force from the fully laden structure would have snapped the support beams. Examinations of the remaining masonry piers at the site, carried out in 1979 by Serbian archaeologists Milutin Garašanin and Miloje Vasić, revealed an important clue. The cement base of the piers showed that the Romans drove support beams into the piers to add strength to the arches.

“The holes gave us the most probable positions for the ends of the arches,” said. The posts driven into the cement base also would have given sufficient stability to the bridge.

Mehrotra and Glišić evaluated the variety of local trees and concluded that European oak, common to the area, could have provided beams both large enough and strong enough to fashion the bridge’s arches and deck. The Romans could have cut the wood and fashioned much of the structure before assembling the bridge.

“They used the same technique we do now, prefabrication and construction on site,” Glišić said.

Glišić said without a definitive historical record, such as Appollodorus’ lost book, there is no way to be sure how the bridge looked. But he said that applying sound engineering analyses can greatly narrow the possibilities.

“We cannot say it really was like this,” he said, “but we can say it very likely was like this.”