T. Leslie Shear Jr., professor of classical archaeology, emeritus, died Sept. 28 at Penn Medicine Princeton Medical Center after a brief illness. He was 84.

Born in Athens to a family steeped in the discipline of archaeology — in the field and in the classroom — Shear was set on an auspicious path which he would follow his whole life. An esteemed archaeologist and scholar who taught and mentored generations of Princeton students, he served as the director of the Program in Classical Archaeology at Princeton and as field director of the American excavations at the Athenian Agora under the aegis of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens. His book “Trophies of Victory: Public Building in Periklean Athens” is considered essential reading in the field.

T. Leslie Shear Jr., 2009

Shear received his bachelor’s in classics, summa cum laude, from Princeton in 1959 and his Ph.D. in art and archaeology in 1966. He began his academic career as an instructor and then assistant professor of Greek and Latin at Bryn Mawr College, returning to Princeton in 1967, where he taught for more than four decades, transferring to emeritus status in 2009.

“‘Bucky,’ as he was known at Princeton, devoted his career as an archaeologist and historian of art to the excavation and study of some of the most important monuments in Athens,” said Rachael DeLue, the Christopher Binyon Sarofim ’86 Professor in American Art, professor of art and archaeology and American studies and chair of the Department of Art and Archaeology. “He supervised many graduate students who would go on to produce research essential to the field, and he is remembered for his expert guidance as students navigated the many areas of expertise, including philology, epigraphy, history, art and architecture, required by their training.”

DeLue remembers Shear’s hospitality when she first came to Princeton. “He will also be remembered for the lovely holiday party he hosted annually at his home in Princeton, and for the perennial and always welcome appearance of an overflowing tray of shrimp. I attended my first Bucky party as a new assistant professor, and he made me feel right at home.”

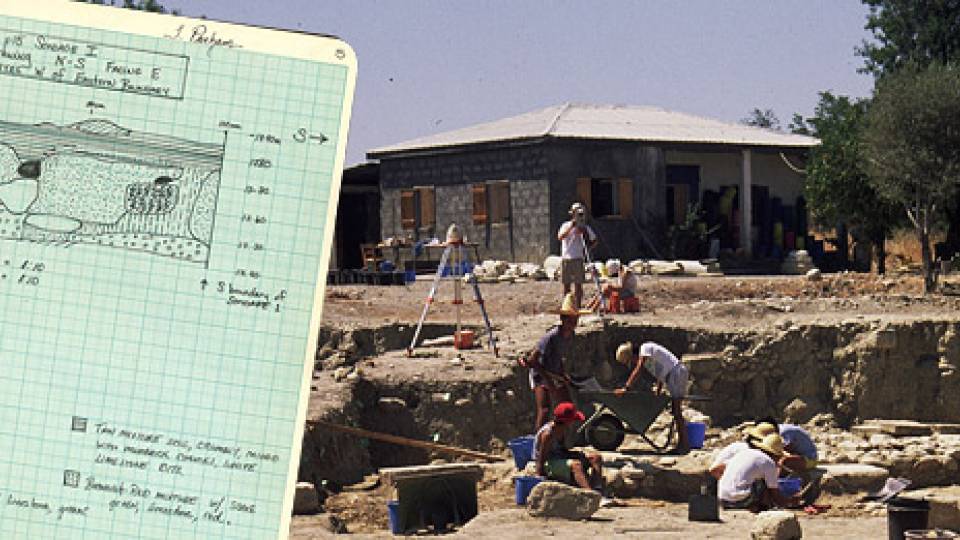

“Bucky was so many things: a rigorous scholar and fine administrator while being shy, wryly humorous, demanding, and generous, and even occasionally difficult,” said Willy Childs, professor of classical art and archaeology and a 1971 graduate alumnus. “Although very concentrated on Athens, he came out to the department’s excavation on Cyprus with his wife, Ione, and his daughter, Julia, and served with distinction, directing excavation in a difficult area: he and his family loved the discipline.”

Childs continued: “But Bucky’s triumph was clearly his dissertation which, much expanded, was finally published in 2016 as ‘Trophies of Victory: Public Building in Periklean Athens.’ This is a meticulous and wide-ranging treatise that is indispensable for the study of Athenian architecture of the classical period.”

Shear’s scholarly contributions also include the book “Kallias of Sphettos and the Revolt of Athens in 286 B.C.” (1978) — a major study which continues to be cited regularly, as well as many articles.

He was born in Athens, Greece, on May 1, 1938. His father, T. Leslie Shear, was a professor of classical archaeology at Princeton, who was then directing the excavations at the Athenian Agora — the central plaza and focal point of community life in ancient Athens. His mother, Josephine, was on the Agora staff.

Although much of Shear’s career was spent on the excavation and the publication of the monuments of Athens, he regularly taught both undergraduate and graduate courses on classical archaeology, Greek and Roman architecture, the Athenian Acropolis, topography and monuments of the Agora, various aspects of the Greek Bronze Age, among others.

Nassos Papalexandrou, an associate professor in the Department of Art and Art History at the University of Texas-Austin, who earned his Ph.D. at Princeton in 1998, said: “I fondly cherish the memory of Shear as teacher, mentor, and, not least, an exemplary field archaeologist. His graduate seminars were masterfully structured. The evidence was meticulously laid out, as if assembling an incredibly challenging jigsaw puzzle, towards building an insightful interpretation about this or that aspect of the monumental development of ancient Athens. He was master of his game. Thirty years on, I often return to my notes taken during his seminars.”

His wife, Amy Papalexandrou, a Byzantinist and professor emerita at Stockton University who also earned her Ph.D. at Princeton in 1998, remembers Shear coming to listen to her dissertation proposal — on the ninth-century church of Panagia Skripou at Orchomenos, an edifice entirely built with ancient blocks. “It was so generous of him to come and listen,” she said. “I was of course petrified, but I remember well his quip about the church: ‘There were enough architectural materials to build anew an entire ancient temple out of all that spoliated masonry.’”

When Shear became field director of the American excavations in the Athenian Agora in 1968, at the foothill of the Acropolis, he returned to the site his father had opened up in 1931 and where work had continued with only a break during WWII.

During the younger Shear’s tenure, which continued until 1994, the excavations were greatly extended to the south, east and especially to the north, beyond the modern Piraeus railway line that had cut across the Agora. In 1981, the team discovered the west end of the famed Stoa Poikile, or Painted Stoa — considered the building that Stoic philosophy was named for — started about 460 B.C. and decorated with paintings by the greatest artists of the day. It was from the building’s steps that the Cypriot philosopher Zeno, in about 300 B.C., began to preach his beliefs, which later became the basis of Stoicism. Among the many important discoveries at Agora was the 1970 excavation of the Stoa Basileios or Royal Stoa, where Socrates was tried and sentenced to death in 399 B.C. (by drinking a cup of poisonous hemlock).

“Field archaeology constantly brings to light new discoveries, new evidence to improve our interpretations of ancient life — from the most exalted works of art to the humblest artifacts of daily living,” Shear said in a 1977 University publication.

In 1980, Shear made the momentous decision to institute the Agora Volunteer Program: for the first time in Greece, the actual work of excavation would be done by student volunteers. The program was an instant success and paved the way in Greece for the field schools that are now common.

His graduate students also spent time at Agora. Carla Antonaccio, professor emerita of archaeology at Duke University, who earned her Ph.D. in 1987, was one of the Agora volunteers in the early 1980s.

“He was famous for his stone-by-stone tours of the excavations in the Agora, where he lectured for hours without notes,” she said. “He was very formal but had quite a wit.”

Susan Rotroff, the Jarvis Thurston & Mona Van Duyn Professor Emerita at Washington University of St. Louis, who earned her Ph.D. in 1976, was a trench supervisor at Agora in the early 1970s.

“An inspiring teacher, his field experience and profound knowledge of the site made him an unfailing guide to me, the perplexed trench supervisor (he was rumored to have read all of the hundreds of field notebooks that form the primary record of the Agora Excavations),” Rotroff said. “When I unearthed a broken Archaic pot full of pure potter’s clay and began to build fantasies about an obscure ancient ritual, he brought me back to earth by reference to a potter’s shop excavated nearby, 40 years before. I would not have had the academic career I have enjoyed without his guidance and support.”

Andrew Sherwood, associate professor and head of classical studies at the University of Guelph in Canada, who earned his Ph.D. in 2000, first met Shear at Agora on baking-hot 117-degree day in 1977, during a site visit when he was attending the American School of Classical Studies at Athens’ summer session.

“He spent a very patient two hours standing in the shadeless space before the Stoa Basileios, explaining its discovery and incredible significance,” Sherwood said. “He then withstood another half hour of questions in the sun, equally patiently responding in meticulous detail, and I was convinced I wanted to come to Princeton and work with him. He always had the rapt attention of his students who could see his growing excitement and we did not want to miss a thing. Among many of us he seemed immortal.”

Mark Lawall, the chair of the managing committee of the American School of Classical Studies, and professor of classics the University of Manitoba, noted that Shear’s long association with the School was exemplified by his meticulous teaching. By way of example, Lawall noted: “In 1992, the topic was ‘Building Inscriptions.’ Each week, he spun out each session like unraveling a mystery, each step led to the next with a cool and brilliant rationality. And, like the greatest mystery stories, his lectures held us spellbound.”

Shear is predeceased by his wife Ione Mylonas Shear, a daughter of the notable archaeologist George Mylonas, who he met 1956 when they both excavated for Ione’s father at Eleusis. He is survived by his daughters, Julia, a senior associate member of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens, and Alexandra Shear; and a grandchild Briar Shear.

The funeral service will take place at 10:30 a.m. Monday, Oct. 10, at Trinity Church, 33 Mercer Street in Princeton. The service will also be livestreamed(Link is external).

View or share comments on a blog(Link is external) intended to honor Shear’s life and legacy.