At the beginning, surrounded by verdant farmland, the archaeological secrets of two ancient cities lay dormant below the surface on a Mediterranean island. That changed when William Childs(Link is external), professor of art and archaeology, emeritus, arrived at that rustic spot on the northwest coast of Cyprus in the early 1980s to explore the possibility of establishing an archaeological expedition for Princeton.

Childs brought with him a handful of graduate students who, under hardscrabble conditions, worked with basic tools — pickaxes, shovels, trowels, brushes and wheelbarrows — while all along taking notes. Little did they know that their efforts would unearth a Cypriot “City of Gold” that would lead to decades of educational opportunities for Princeton students.

Professor Emeritus William Childs (foreground) works with Emma Ljung (in white) and Tina Najbjerg in a trench at Polis Chrysochous in 2007. (Photo courtesy of the Department of Art and Archaeology)

Since a course called “Archaeology” was introduced on campus in 1843, the University has challenged students in the classroom and on excavations abroad to experience the culture, history, art, architecture and politics of the ancient world. In 1883, a formal Department of Art and Archaeology(Link is external) was founded.

A century later, the Princeton University Archaeological Expedition at Polis Chrysochous — that scrap of land in Cyprus — was established with Childs as director. The excavation set the stage for hands-on learning experiences for hundreds of Princeton students; new academic courses; and a major loan exhibition, “City of Gold: Tomb and Temple in Ancient Cyprus(Link is external),” on view until Jan. 20, 2013, at the Princeton University Art Museum(Link is external).

Three and half years in the planning, the exhibition coincides with Cyprus serving in the rotating presidency of the European Union. There are other Cypriot shows being mounted concurrently in Europe. “This is the ‘American wing’ of that celebration,” said J. Michael Padgett(Link is external), curator of ancient art at the art museum and co-curator of “City of Gold” with Childs and Joanna Smith(Link is external), associate professional specialist and lecturer in art and archaeology.

Smith points out details of a terracotta funerary statuette depicting a mourning woman made in the fourth century B.C.E., which would have been placed in the “dromos,” or passageway to a Cypriot tomb. From left, freshmen Rei Matsuura, Zoë Perot, Carly Pope and Maggie Kent look on. (Photo by Denise Applewhite)

The exhibition documents more than three millennia of civilization with 110 artifacts, most exhibited for the first time: seals, coins, lamps, bronzes, ceramics, painted fresco, gold jewelry, vessels and statuettes. They are displayed in galleries custom-designed to give visitors the greatest possible sense of their original context.

The show chronicles a significant chapter in the history of archaeology at Princeton. The majority of the artifacts — about half of which were found by the Princeton team — are on loan from the Department of Antiquities in Cyprus; 15 are from the British Museum in London, and two are from the Louvre in Paris. “Everything we find stays in Cyprus, it’s the property of the Republic of Cyprus, and it’s been that way for many years,” Padgett said.

“‘City of Gold’ is a great moment to reflect on Princeton’s influence on archaeology in ways that have shaped our understanding of the ancient past,” said James Steward(Link is external), director of the museum.

The museum as laboratory

This fall, Smith, a 1987 Princeton graduate who studied with Childs and joined the project at Polis Chrysochous in 1988, is teaching the freshman seminar “City of Gold: Archaeology and Exhibition,” centered on the show.

“This seminar allows students to experience both the practical and theoretical aspects of museum exhibition of antiquities,” said Smith, who became assistant director at Polis Chrysochous in 2001. “The importance of context in archaeological research is rarely included within museum displays that emphasize the object, often as an isolated work of art.”

To help students learn about the role of context when thinking about the relationship of archaeology and exhibition, Smith uses the resources of the art museum in several ways.

The semester began with a visit to the museum’s galleries of ancient art. Students viewed mosaic pavements from Antioch-on-the-Orontes in Turkey — where Princeton archaeologists joined the Musées nationaux de France in 1932 to excavate until the outbreak of war — placed on the floor, as they would have been in the houses of ancient Antioch.

Freshman Maggie Thompson speaks to her classmates about silver coins from the city of Marion, displayed in a case with a small limestone head of a man wearing a wreath and a headband with flowers. (Photo by Denise Applewhite)

“We talked about how you bring that context to life within an exhibition space,” Smith said. “How do you make that relevant for people within a museum, and why is that important to do?”

Students used stone and terracotta sculptures from the museum’s collection to “create a display that would give people a sense of what early excavations by the Department of Art and Archaeology contributed to our knowledge of the ancient world,” Smith said.

Padgett, who has participated in the dig at Polis Chrysochous since 1996, arranged for the students to have two sessions in the ancient art precept room lined with floor-to-ceiling glass-fronted cases of ancient objects.

“Slides are all well and good but there’s nothing like the real thing, especially for a three-dimensional object,” Padgett said. “The students get to see how these objects feel, smell and look and how much they weigh. It excites them; it adds piquancy to the experience. Many a future art historian or archaeologist got started just that way.”

Recently, the students toured the exhibition “to experience how the design of ‘City of Gold’ helps define the physical and historical context in which the artifacts were originally found,” Smith said. “The students are using the exhibition as a laboratory.”

Freshman Maggie Kent presents a section of the “City of Gold” catalogue on gold jewelry she studied as part of an assignment for the freshman seminar. (Photo by Denise Applewhite)

Large maps and enlarged photos of the excavation sites and objects in situ as well as wall texts help build context for the artifacts on display.

The first room is designed to create “a schematic ‘dromos’ (tomb entrance) to give you a sense of what was found during the expedition,” Smith explained to the students.

A large photo of a tomb entrance serves as a backdrop to one of the key pieces in the exhibition: an imported ‘kouros,’ or nude Greek male youth — the only one found on Cyprus — on loan from the British Museum. “This is his ‘moment of glory,’ being displayed front and center. See how the lighting highlights his collarbone and the details of his pectoral muscles,” Smith said.

The lighting made an impression on freshman Ryan Budnick. He said he enjoys learning how to “look at museum design with a critical eye and the process that leads to specific design decisions: Why is this lighting on this piece more dramatic than on that piece? How can we best inform the viewers of a piece’s context without resorting to lengthy text?”

The students discovered there is an art to choosing paint colors for gallery walls. “Colors are selected to help move the narrative along, to complement the objects and to summon a particular idea in place or time,” said Michael Jacobs, principal museum preparator.

“I had not realized before now how important are what I had previously thought were minor details — such as the color of the paint on the walls or the type of base that an object sits on — and how they can really impact a viewer’s impression of each piece,” said freshman Maggie Thompson.

Stephen Gilbert, a 1992 Princeton graduate, captured a view of the archaeological site at Polis Chrysochous in 1991. He said his experience in Cyprus was “life-changing.” (Photo by Stephen Gilbert)

In another gallery, students watched a 10-minute video depicting the 3-D reconstruction of four buildings at Polis Chrysochous.

In summer 2011, working under the supervision of Smith and computer science(Link is external) professor Szymon Rusinkiewicz(Link is external), Ian McLaughlin, a 2012 graduate who majored in computer science, and classics graduate student Mali Skotheim went to the site and used 3-D scanners to document many of the objects designated for the exhibition.

In spring 2012, Smith, Childs and Rusinkiewicz co-taught “Modeling the Past: Technologies and Excavations,” which set forth a specific challenge to the students — to “virtually” raise four of the buildings: an Archaic sanctuary, a Classical temple, a Hellenistic building and a Late Antique basilica.

“The 3-D modeling course and the freshman seminar represent the academic underpinnings of this exhibit, as well as the archaeological methodologies used at Cyprus,” Steward said. “Modern museum practice is to show how technology enhances the art itself, and the 3-D modeling video does that.”

Using thousands of scans taken by McLaughlin and Skotheim, photographs and other primary source material, Nikitas Tampakis, one student from the seminar, created the final computer-animated video, not unlike a virtual house tour on a realtor’s website. The video shows not only how these buildings may have looked in their original state but also how many of the artifacts in the exhibition would likely have been placed inside.

This computer-animated video was created by Princeton students in the spring 2012 class “Modeling the Past: Technologies and Excavations,” which challenged them to “virtually” raise four of the buildings from the Cyprus site using thousands of scans, photographs and other primary source material. (Video courtesy of the Princeton University Art Museum)

An archaeological quest

Childs came to Princeton as an undergraduate in 1960 with an eye on foreign affairs and economics. After taking a Greek art course taught by Erik Sjöqvist, who had participated in a Swedish expedition to Cyprus in 1929, Childs changed his focus to antiquities during his undergraduate and graduate studies at Princeton.

Childs taught Greek and Near Eastern art and archaeology for 36 years. In 1979, Vassos Karageorghis — then director of the Department of Antiquities of Cyprus, now a professor emeritus at the University of Cyprus — came to speak at Princeton and suggested to Childs that he “come across the water” and dig in Cyprus.

The modern town of Polis Chrysochous lies above two ancient cities: Arsinoe, circa 270s B.C.E.-1500s C.E., and the city-kingdom of Marion, founded c. 800 B.C.E. at the mouth of the river Chrysochou. “Polis” is the Greek word for city and while “chrysos” means gold, there is no evidence of naturally occurring gold in the region. However, 19th-century excavations unearthed hundreds of tombs that contained intricately crafted jewelry, much of it gold — as well as Greek vessels and thousands of funerary sculptures.

Childs said that the “gold” moniker might “refer to the fecundity of the valley watered year round by springs — the only part of Cyprus that is largely green through the summer — but that is just a hypothesis.

“So, we had rich cemeteries but no actual location for the cities that produced these cemeteries,” he said. The quest to discover the story behind the cemeteries launched more than a quarter-century of digging that has uncovered sanctuaries, public buildings, workshops and private residences spanning centuries.

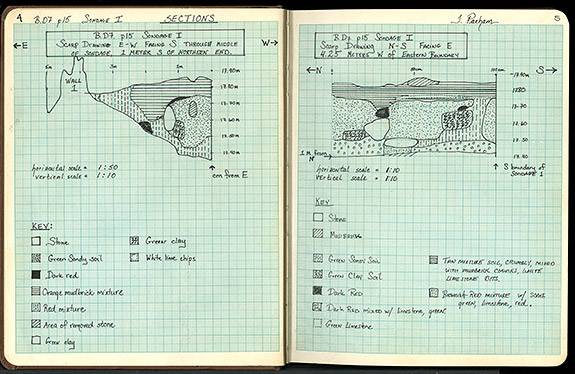

Archaeologists keep extensive notes of their on-site work. Shown here are pages from the archaeological notebook of Tally Parham, a 1992 Princeton graduate who spent the summer of 1991 in Polis Chrysochous. (Photo courtesy of the Princeton Cyprus Expedition)

Generations of Princeton students received their first significant archaeological training there. Childs knew undergraduates had no experience; he simply taught them. “They were just expected to arrive and perform — and they all did. Was it rewarding? Yes. What does one teach for?”

Many of the students who went to Cyprus have forged careers in archaeology; others have taken the lessons they learned and applied them to a variety of pursuits.

Joan Breton Connelly, a 1976 graduate who majored in classics and was at the dig for the first season in 1983, is a professor of classics and art history at New York University. She founded the New York University Yeronisos Island Excavations and Field School in Cyprus, where she has served as director for 22 years. “Participation in the excavations at Polis Chrysochous launched me on a wonderfully fulfilling career path as a field archaeologist and scholar,” Connelly said.

Stephen Gilbert, a 1992 Princeton graduate who majored in civil engineering and operations research, spent the summers of 1990 and ‘91 making one of the earliest 3-D models of Childs’ archaeological trenches. “How much better is it to experience challenges firsthand with a real-world need than in a textbook? My experience in Cyprus was life-changing,” said Gilbert, now assistant director of Iowa State University’s Virtual Reality Applications Center and assistant professor of industrial and manufacturing systems engineering.

While formal digging at Polis Chrysochous ended in 2007, research is still being conducted on the findings, and Princeton students continue to work at the site. Over fall break, Smith accompanied Adam Maloof(Link is external), an associate professor of geosciences(Link is external); Frederik Simons(Link is external), an assistant professor of geosciences; and students in the freshman seminar “Earth’s Environments and Ancient Civilizations (in Cyprus)” to conduct a geophysical survey at the site.

Smith underscored that all of the contributions students have made over the past three decades — in the classroom or on site — “built on the work of students from the past, and it was made clear to them that their work was also a formal part of the project that would be archived, on which future students would be building.”

These contributions are their own treasure trove — a “City of Gold” — for future scholarship and discovery for generations of Princeton students to come, she noted.