The spring course “The Art of Living” was part of the Program for Community-Engaged Scholarship (ProCES), bridging academics and service. Pictured from left: Sophomore Sabrina Sequeria; senior Isaiah Nieves; Basile Baudez, assistant professor of art and archaeology; junior Sydney Wilder; and senior Amarra Daniels talk about urban renewal issues during a visit to an underserved neighborhood in Trenton, New Jersey.

Heat in the living room. Street lights. Apartment buildings. How did the creature comforts of home and public life — from pubs and flush toilets to crime control and kitchen gardens — develop?

This spring, 10 Princeton undergraduate students in the course “The Art of Living” set out to discover connections between the past and present, with a particular focus on an underserved neighborhood in Trenton, New Jersey, the state capital near Princeton.

The cross-listed course is part of the Program for Community-Engaged Scholarship (ProCES), bridging academics and service. Throughout the semester, students attended community forums led by the nonprofit East Trenton Collaborative (ETC), a community organizing and development initiative in the East Trenton neighborhood of Trenton’s North Ward.

Assignments included generating a summary based on students’ observations and group discussions with residents at the forums, and recommendations that will be incorporated into ETC’s 10-year strategic neighborhood plan.

The instructor: Basile Baudez, assistant professor of art and archaeology, specializes in 18th- and 19th-century European architecture, and the role of architecture in politics and society. His current project is “Inessential Colors,” a book on the history of the use of color in architectural representation in Europe between the 17th and 19th centuries.

Baudez, who joined the Princeton faculty in fall 2018, from Paris-Sorbonne University, learned about ProCES and other University programs at the two-day orientation for new faculty members, which is hosted by the McGraw Center for Teaching and Learning. He was immediately inspired to develop a course.

He credits Leah Seppanen Anderson, associate director of ProCES, with connecting him with ETC and with “shaping what types of assignments struck the balance between historical and contemporary situations,” he said.

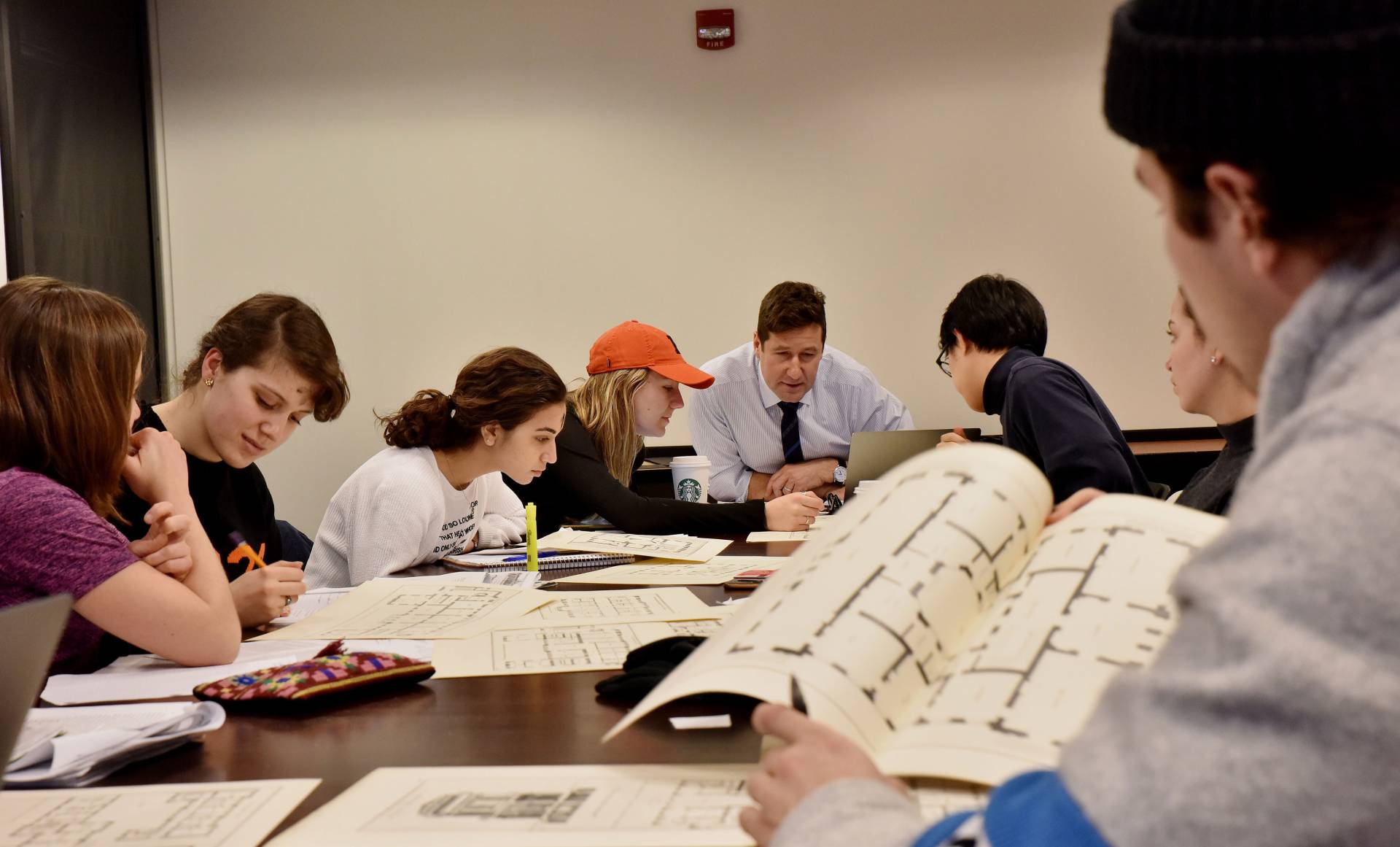

Students pore over large photocopies of 18th-century engraved plans of Paris townhouses to jumpstart a discussion of how architecture informs domestic life.

Studying the past: Many of the readings focused on the development of urban infrastructure and domestic spaces in late 17th- to early 20th-century Paris and London. On March 6, the class discussion explored “Masters and Domestics.” Seated around a long table in McCormick Hall, the students pored over large photocopies of 18th-century engraved plans of Paris townhouses.

Baudez asked, “Where is the kitchen in terms of the rest of the house. Has anyone found it?”

“As far away from the bedrooms as possible,” one student said.

“Right,” Baudez said. “Fire hazard is one reason. Noise. Smell. Heat.”

Focusing on the dining room, Baudez described how, before the 1860s when passing of dishes became the norm, food was served all at once.

“The diners help themselves,” he said. “Then the domestics take the leftovers and that’s what they eat. If there’s more than enough for the domestics, they give it to the poor. It’s a chain. The more lavish the house, the more spreading the rest of your food to the neighborhood. That’s very important in terms of ‘outside/inside.’ The outside benefits from the inside.”

Baudez asked how this “outside/inside” concept translates to the East Trenton neighborhood.

One student said, “I feel like Trenton is missing ‘the big house’ facilitating food and services.”

Another student compared “the big house” to the municipal government and said: “Government officials aren’t necessarily seeing and experiencing what’s happening in East Trenton. That’s why we need these neighborhood forums.”

Elena Sauceda-Peeples (left), director of the East Trenton Collaborative (ETC), a community organizing and development initiative, gives students a tour showing them rehabbed housing units as well as damaged streets and poor signage that lead to traffic and safety issues.

Engaging in the present: As the sun dipped below the horizon on an early April evening in East Trenton, about two dozen residents filled their plates with submarine sandwiches and settled around three tables in the main room of a small converted church, the headquarters of the East Trenton Collaborative.

Before joining the residents, four of the Princeton students met with ETC director Elena Sauceda-Peeples in a makeshift office that also serves as a supply room.

“By helping us capture residents’ ideas, you’re making a significant contribution,” she told them. “The work we do here is to elevate residents’ views and voices.”

The topic of this evening’s forum was “Public Spaces and Transportation.” The students, seated one or two at each table, participated in a neighborhood planning activity. Each group completed a worksheet on one of three topics: programming in and for public spaces; neighborhood identity, branding and signage; and complete and safe streets. The worksheet served as a discussion guide, focusing on strengths, weaknesses and opportunities.

The residents, some speaking in Spanish, voiced a variety of experiences and concerns.

“My street has a lot of holes. I’m tired to see kids playing and motorcycles and cars zooming by. It’s dangerous.”

“I’m a landscaper. They’re filling those holes with sand, not blacktop or cement. After a rain, my neighbor’s car was messed up.”

Others bemoaned the lack of adequate public transportation and signage to warn drivers they are entering a school zone, to indicate children at play, or to mark access to parks and bike trails.

The recommendations in the students’ summaries ranged from signage to address specific issues; beautification projects such as gardens, murals and public art installations to build community identity; a weekly newsletter from ETC to help residents feel informed and build their trust in ETC’s process; and exploring logistics for transporting residents to Newark so they could speak at the NJ TRANSIT board meetings, which are open to the public.

At the start of the semester, Sauceda-Peeples gave the students a walking tour of the neighborhood so they could experience some of the challenges the residents face on a daily basis. Lack of painted crosswalks results in dangerous jaywalking; garbage is strewn around the park’s greenspace; freight trucks impede traffic flow on certain residential streets and compromise homes’ foundations; and public transportation consists of only one bus route that comes through the neighborhood every two hours.

Sauceda-Peeples (center left, in floral top) and Princeton seniors Daniels and Nieves engage in a discussion of residents’ concerns and ideas during one of several neighborhood forums the students attended throughout the semester. Recommendations from the students, drawn from their participation in the forums, will be incorporated into ETC’s 10-year strategic plan.

The nexus of academics and service: Trisha Thorme, director of the Program for Community-Engaged Scholarship, said “students were able to connect the lived experience of Trenton residents to the themes of the class.”

She said ProCES helps dissolve the lines between the classroom and the real world. “One of the things I want students to learn through this kind of project is the importance of knowledge and research in creating social change,” she said.

Sauceda-Peeples noted the benefits of a service project that lasts a whole semester.

“Students who are able to spend more time in a community are able to understand the nuances of that community,” she said. “Students see and hear directly from community members, rather than through secondary sources. They are able to reflect on earlier experiences, ask more informed questions, and make meaningful connections between their studies and the real world.”

Baudez said: “The question of whose voice is heard in this context is essential. What I am most proud of is that the students learned how to listen to those most immediately impacted by the situation instead of imposing solutions from outside or taking knowledge secondhand.”

The take-away: Baudez said that he hopes the students, no matter what their majors, “will reflect on the fact that history helps to put into question our most basic assumptions. The course showed that what we take for granted as part of contemporary society in terms of essential needs and comfort is, in fact, the result of a historical process — and that not far from Princeton, communities are still struggling to access or maintain this level of comfort.”