The spring course “A River Runs Through Us” explores the natural environment of New Jersey’s Millstone River through art, ecology and culture. On April 9, students paddled from the base of the bridge that carries U.S. Route 1 over the Millstone into the undeveloped swamp forests and marshes that line the upper river.

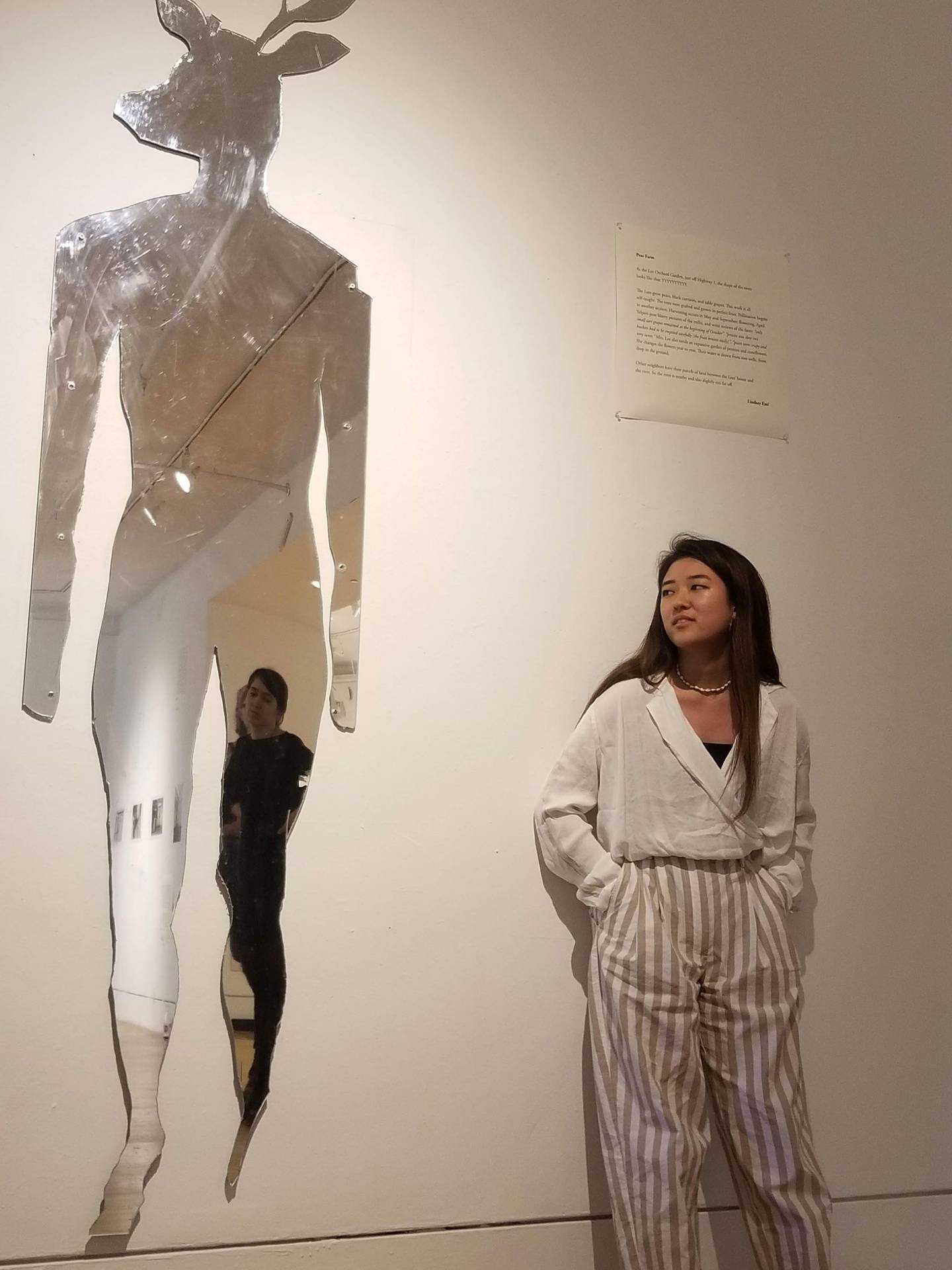

An 8-foot deer shape cut from a discarded mirror stood along one wall of the Lucas Gallery at 185 Nassau St. on the Princeton campus, its humanoid body reflecting the people gathered around a table set with native New Jersey plants, a sun-bleached turtle shell and discarded bottles stuffed with secret messages.

The recorded sound of rain falling on the trees along the Delaware and Raritan Canal State Park towpath filled the small gallery as Isaiah Nieves talked about the natural spring that rises from beneath Princeton to form Harry’s Brook, which runs through town via an underground concrete culvert.

Jeff Whetstone, a professor of visual arts in the Lewis Center for the Arts and Princeton Environmental Institute (PEI) associated faculty, wanted the course to instill an appreciation for the local environment by having students engage with the river as well as the people and landscapes surrounding it. “It changed my whole idea of how to teach a class,” Whetstone said.

“This is what’s left of it,” said Nieves, a Princeton senior in art and archaeology who is earning a certificate in visual arts, gesturing toward his photographs of the tangle of PVC pipes in the lowest level of the Spring Street parking garage that attempt to confine the spring as it defiantly surges forth toward Lake Carnegie and the Millstone River.

“These photographs represent the ways various aspects of the Millstone watershed have been built over,” Nieves said. “I tried to uncover the ways in which we try to suppress wilderness.” But as the puddles and water stains the spring has deposited around the base of the pipes attest, nature often finds a way through even the most intricate of barriers.

The exhibition was the culminating event of the spring course “A River Runs Through Us,” which explored the natural environment of New Jersey’s Millstone River through art, ecology and local culture. Cross-listed with anthropology, environmental studies and visual arts, the course was developed and taught by Jeff Whetstone, a professor of visual arts in the Lewis Center for the Arts and associated faculty in the Princeton Environmental Institute (PEI), and Nomi Stone, a postdoctoral researcher and lecturer in anthropology.

Co-instructor Nomi Stone, a postdoctoral researcher and lecturer in anthropology, proposed the course as a way of having students explore the world by animating local spaces through personal experiences and topographies. “I was interested in their engagement philosophically with the river,” Stone said. “What is this body of water that winds through this place and has a complicated relationship with it?”

Just under 39 miles long, the Millstone winds through one of the most densely populated areas of the country. It flows into Princeton from the east, passing under U.S. Route 1 to provide water for Lake Carnegie, then turns north to run parallel to the canal before emptying into the Raritan River near Manville, New Jersey.

Throughout the semester, students in the class engaged with the river as well as the people and landscapes surrounding it as a way to experience the subjugation and resilience of nature — and how people drive both. They paddled the river and walked along its banks. They visited human-made dams and interviewed people living along the river, as well as council members, artists and birdwatchers invested in the river's health, all with help from the Program for Community-Engaged Scholarship (ProCES) in the Office of the Dean of the College. People from organizations such as The Watershed Institute spoke about the river’s biology and the efforts to restore and protect its watershed. As part of their final project, students expressed themes they took from the class through artwork.

These interactions framed the Millstone as a dynamic living entity deeply connected to local land, culture and community, said Whetstone, who last year taught a class about life along the lower Mississippi River as part of his PEI Urban Grand Challenges project that focused on climate and the fate of New Orleans.

Maria Fleury, a first-year student from Rio de Janeiro, observes a snake — one of several encounters with wildlife the students experienced along the Millstone's riverbank. “I feel like every interaction with nature is a multidimensional puzzle,” she said.

“I’m really interested in how we shape rivers and how rivers shape us,” he said. “The narrative we tell about the Millstone changes according to our culture,” he said. “At one point, it was a river about the transportation of resources and powering grist mills. Now it’s about the nascent wildlife returning to it. It’s a river about recreation and beauty, and providing water to a growing population.”

Stone, who also has taught in the creative writing program, proposed the class to Whetstone after reading “Dart” by poet Alice Oswald, which uses local voices to create a narrative of the River Dart in England.

“In some ways, this class could be taught about any subject,” Stone said. “Whatever is local is interesting to me. The students became acquainted with the river as a means of inquiry about the world. We wanted them to be able to mobilize ways of asking questions about the world and be alive to what is around them. To be moving in the world and asking questions is, I think, the best classroom.”

Sophomore Amy Amatya created an 8-foot-tall humanoid deer from a discarded mirror as part of the May 15 exhibition in which students expressed themes they took from the class through artwork.

The instructors learned about the Millstone alongside the students, said Stone, who will be an assistant professor of poetry at the University of Texas-Dallas next year. The journals, papers and artwork the students produced contributed a substantial amount to the scholarship that exists about the Millstone, she said. Stone will incorporate the Millstone River into her next collection of poems, "Fieldworkers of the Sublime."

“Jeff and I didn’t know very much about the river," Stone said. "What we do know is how to learn about something. The goal was to animate this river for this class. We were really making something together and figuring something out together.”

By closely interacting with a local ecosystem, students in the course also were able to observe global issues such as population growth, habitat loss, access to water and increased flooding due to climate change on a more intimate scale, Whetstone said. He plans to teach the course again.

“With climate change, rivers are going to have a lot more to say to us — they’re going to start speaking louder and louder and louder,” Whetstone said. “The feeling of being on the river in the snow, knowing what being inside a beaver lodge feels like — these are experiences that are original and are the impetus for doing work in the natural sciences and conservation. They are the source material for being inspired to fight for the environment.”

Senior Remi Shaull-Thompson knew every “rock and rapid” of the local creek when she was growing up in Pylesville, Maryland. For many students at Princeton, however, four years of living within walking distance of the Millstone’s waters can pass without ever knowing much about it.

“Our field trips helped me see both how the lake is fed by the Princeton community and how it connects to the rest of New Jersey,” said Shaull-Thompson, who will graduate from Princeton on June 4 with a degree in English and certificates in creative writing and environmental studies. “Just by following the river you'll see so many different worlds, from orchards to warehouses.”

Senior Remi Shaull-Thompson crawls inside an abandoned beaver lodge along the Millstone. “I found the experience both humbling and unnerving. The protection of the lodge implied the threat of danger outside, and when you're inside you feel small,” Shaull-Thompson said.

For the final exhibition in the Lucas Gallery, Shaull-Thompson created the dining table set with plants, litter and other objects she collected along the canal towpath. While the course explored the influence of people on the river, it also demonstrated that we are never completely severed from nature, even in a densely populated area, she said.

“Humans' relationship with nature was a big theme,” Shaull-Thompson said. “Wilderness is not separate from us. The river is an entry point to rediscover wildness, as something that winds through our countryside, suburbs and cities.”

On April 9, students paddled in canoes provided by Princeton Outdoor Action from the base of the bridge that carries U.S. Route 1 over the Millstone into the low swamp forests and sedge marshes that melt into the river’s languid current. The sun shone on the new verdant heads of pond lily protruding from the mucky riverbed as the students’ paddles splashed in the reddish-brown water colored by silt and the tannins of rotting oak leaves. Turtles recently awakened from their winter slumber balanced above the water on sunny tree limbs as female Canada geese hunkered down on their nests when the flotilla passed by.

Students came across a nest of Canada goose eggs during the April 9 canoe trip.

The 2 miles of winding waterway bore little resemblance to the beaches of Rio de Janeiro from where first-year student Maria Fleury came to Princeton.

“I have very little familiarity with untouched nature — I was a little outside of my comfort zone,” said Fleury, who is interested in civil and environmental engineering. “The Millstone is in Princeton, it’s next to us, but it’s like a different universe.”

She recently walked along the Washington Road stream in the woods behind the Frick Chemistry Laboratory “observing little bubbles go their separate ways,” she said.

“I think being close to the flow of water allows for the energy from the environment to flow through you in a different way,” Fleury said. “Something magical about this class was that it’s very experimental. I feel like me, Maria the person, not Maria the student, was involved in this class. It opened my eyes to the environment of Princeton beyond the University.”

Sophomores Lindsay Emi (left) and Zoie Nieto (right) trudge across the low-lying peninsula at the confluence of the Millstone River and Bear Brook. The course used experiences in the Millstone’s environment to demonstrate the subjugation and resilience of nature.

In a page from his class journal, Christopher Wilson, a sophomore studying art history with certificates in archaeology and visual arts, reflected on his sudden descent into darkness and confinement as he entered a model beaver lodge the class built in the Lewis Arts complex CoLab in March. As an active-duty Marine for five years before coming to Princeton, Wilson — who took the course to gain new perspectives he could implement in his sculpting — most identified with the Pacific Ocean. Yet, he was moved by the simulated abode of a riparian rodent.

“Dare I say we had completed the first steps in becoming beavers ourselves. It was an utterly transformative process,” Wilson wrote after squeezing his broad-shouldered frame through the small entrance hewn from wood and leaves. “A feeling of smallness, uncleanliness and peace washed over me as I crawled into the beaver lodge. I was transformed and saw life through different eyes.”

In March, students from the class constructed a model beaver lodge in the Lewis Arts complex CoLab. Sophomore Christopher Wilson (far left, standing) wrote of the experience in his class journal, “As we gathered our materials for the build, I was thinking about my connection with the Millstone on a personal level.”

That feeling was echoed by Stone, Whetstone and several students when, during the canoe trip, they were able to crawl inside an abandoned beaver lodge that was mostly intact. "I found it electrifying to be in a space that was so viscerally animal," Stone said.

“Crawling into the beaver lodge was one of the most emphatic natural experiences I’ve had, and I’ve been all over the place — and this was literally a mile and a half from my house,” Whetstone said.

“A big part of this class was about appreciating the landscape you’re in,” he said. “People don’t see this landscape as having some kind of power or charisma because it’s not California or Vermont. But it is wild and completely verdant. There’s an incredible amount of wildlife on the Millstone and it’s beautiful. A river does run through us — we take from it and contribute to it every day.”

Shaull-Thompson and Emi help build the frame of the lodge the class constructed in the CoLab.