Besides working as the engineering school’s associate dean for undergraduate affairs, Peter Bogucki is a noted archaeologist specializing in Neolithic cultures of northern Europe. His recent book, The Barbarians, received the 2018 Popular Book Award from the Society for American Archaeology.

The Barbarians examines the prehistoric cultures of Europe that existed before coming into contact with the Greeks and Romans as well as the societies that remained outside the frontiers of the Roman Empire. Bogucki uses the archaeologist’s tools to demonstrate the sophistication of civilizations that are more typically treated as a backdrop for the story of Rome. Despite their skills in art, metalworking and farming, these cultures never developed writing. Because they left no written records, it is up to archaeologists like Bogucki to write their histories.

Below, Bogucki answers a series of questions about the book and his research.

I know the book addresses this, but why did you choose Barbarians as the title? The cultures you describe are sophisticated and complex.

Peter Bogucki, associate dean at the Princeton University School of Engineering and Applied Science and an archaeologist. His latest book is "The Barbarians."

I originally wanted to call it “Meet the Barbarians” or “The Barbarians Then and Now” but the publisher, Reaktion Books, has it as part of their Lost Civilizations series, so in the end, they said it had to be just “The Barbarians: Lost Civilizations” alongside The Etruscans, The Goths, The Indus, The Persians, and Egypt. We can also blame the Greeks for the use of the word “barbarian,” which they used to refer to everyone who didn’t speak Greek.

Yes, the peoples of the Barbarian World were sophisticated and complex, on a par with the celebrated societies of the Mediterranean except for one big thing: they did not have a written language. Those of us who study ancient Europe often use the word “barbarians” in a certain ironic sense. Yes, violence was endemic and they probably had all sorts of practices that we’d frown upon, but the Greeks and Romans were no angels either. But since the pre-literate societies of Europe north of the Mediterranean are often dismissed as inconsequential, those of us who know otherwise embrace the barbarian identity. And calling the people you study “barbarians” also sounds cooler than “later European prehistory.”

It’s a very broad use of the word “barbarian” since some would prefer that it be reserved for societies that were actually in contact with Greeks and Romans, but I think it makes sense to expand it, since they are part of a much larger geographical milieu and show continuity from previous millennia.

A fascinating aspect of the book is the critical role that literacy plays in history's assessment of cultures. It is almost like preliterate cultures cannot speak for themselves so they are overshadowed by the literate contemporaries. Do you feel that archaeologists can give voice to these cultures?

Absolutely. Without documents written by the peoples themselves, the only way we know about them is through their archaeological remains: how they made things, what they threw away, what they ate, where they settled, the types of buildings they built, how they buried their dead, and all sorts of other information. Now we can tell how they moved around (with strontium isotope ratios) and to whom they were related (with ancient DNA).

On the other hand, writing can give us insights about motivation and intent, which isn’t really possible to get from the material remains alone. But as I stress in the book, written accounts always have an agenda, whereas people don’t throw stuff away with a thought of how it will appear to an archaeologist in several thousand years.

One of the best examples of archaeology giving a voice to those who cannot speak for themselves is what we know about the everyday lives of enslaved Africans in the Caribbean and antebellum southeastern U.S. who were generally not allowed to learn to read and write. We know that they had to supplement plantation rations through hunting and collecting. We know that they maintained African traditions in the pottery they made. These facts are not known from contemporary accounts written by the literate people in the antebellum South. The same is true of ancient Europe, particularly the people who lived long before the Romans and Greeks as well as those who lived at the same time but far beyond the frontiers of the classical civilizations.

How did you begin studying these barbarian cultures? What most fascinates you about them?

Cover of "The Barbarians" by Peter Bogucki, published by Reaktion Books as part of its "Lost Civilizations" series.

I originally hoped to be a journalist, but my father encouraged me to take an anthropology course at the University of Pennsylvania. I did, and I was fascinated. Prehistoric archaeology is traditionally a subfield of anthropology in the United States, so as I took more anthropology courses I kept coming back to archaeology. Originally I was drawn to North American archaeology, but during the summer before my junior year at Penn, I went on a summer study program to Kraków, Poland. There was a young woman from Boston participating in the program, and she mentioned that an archaeologist had spoken at her school and she’d found the topic interesting. Seizing the moment, I suggested that we visit the Archaeological Museum in Kraków. There I saw stone tools and other artifacts that were just like in the textbooks. I came back to Penn that fall and began to take courses in European prehistory, and then I went up to Harvard for my Ph.D. And the young woman from Boston and I are celebrating our 40th wedding anniversary this year.

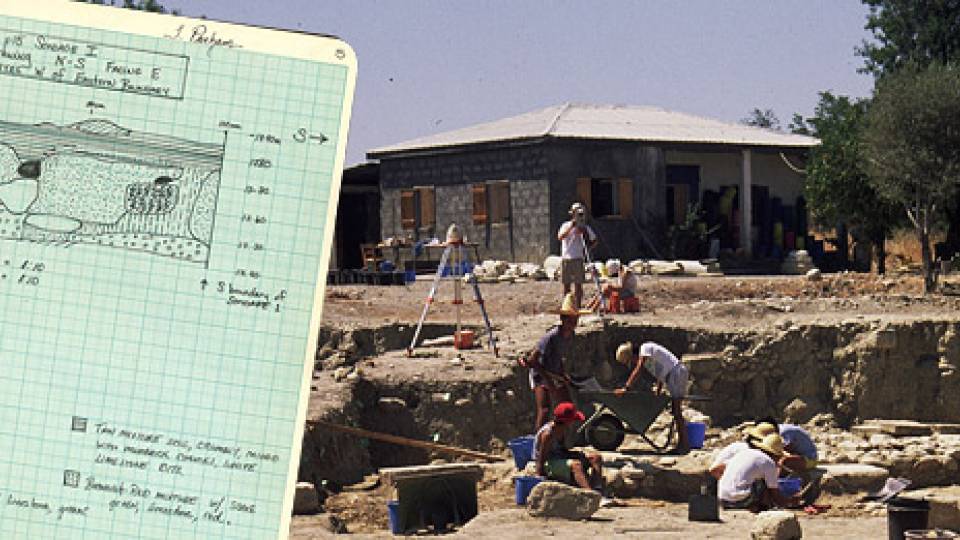

The act of unearthing something that was last seen by someone thousands of years ago is probably one of the biggest thrills of archaeology. But that’s not all there is to archaeology. The practice of prehistoric archaeology also involves piecing together information from many different sites or applying various analytical techniques to figure out something about how people lived in the past. So we’re not interested in the most beautiful artifact, or unique finds. They’re interesting, don’t get me wrong, but we can’t do much with one-of-a-kind things. It’s more important to look at patterns over time and space. Archaeology is the only field that can study the human experience over immense spans of time, many centuries or even millennia, going back millions of years. We’re less interested in events and more about changes over time and interactions between different groups of people across space. I also personally am drawn by the environmental aspects of archaeology, since we need to know how they used the resources in the world around them, how they adjusted to changes, and how they had an impact on their environment. So it’s also a soft way of doing environmental science for me.

Are there lessons we can learn from these cultures? Are there lessons we can learn from the relations between the Romans and the barbarians that surrounded them?

Although the publisher wanted me to bring the barbarian story up into the present, I really stay away from drawing modern analogies to what we see in the Barbarian World and in its interactions with the Greeks and Romans. In Europe, that past is never too far below the surface, and it’s often mobilized to make some modern point, often erroneously. For example, the modern preference of the French for wine and the Germans for beer is often attributed to fact that Gaul was part of the Roman Empire and Germania Magna was not. But we know that the barbarians loved wine when they could get it, so this reasoning doesn’t hold up. I think that it’s crucial to learn about prehistory to understand the totality of the human experience and that it didn’t just begin with writing. If people choose to draw modern lessons from it, then that’s fine, but they run the risk of making false analogies.

What do people tell you they find most surprising about these cultures? What do they seem to find most interesting?

Everybody seems to focus on something different. For some, it’s the way scientific methods like strontium isotope ratios have expanded our understanding of human mobility. For others, it’s the exquisite Irish Bronze Age goldwork. Megalithic tombs have their fans. From reader reaction, I’m finding that in the course of their travels many people have visited an important site or monument in barbarian Europe, but they didn’t find out about the broader context. And of course counteracting the bias toward the literate classical world in history books comes as a revelation for many who say they had no idea what else was there. Since the story I tell in The Barbarians is really just a highlight reel of the big picture of European prehistory, there’s a lot more out there for readers to discover on their own.