Name: Wendy Laura Belcher

Title: Assistant professor of comparative literature and African American studies

Scholarship: Belcher specializes in medieval, early modern and modern African literature. One of her key interests is in how African thought circulated in Europe before the 19th century, which she explores in her latest book by focusing on the influence of Ethiopian thought on the work of the English author Samuel Johnson. In 2011, Belcher spent a year in Ethiopia on a Fulbright fellowship researching ancient manuscripts illuminating the lives of women now regarded as saints in the Ethiopian Orthodox Church, which dates back to the fourth century. She also took the opportunity to photograph a range of scenes and subjects during her visit. Stories from Ethiopia and the African continent have resonated with Belcher since childhood, when she lived in Ethiopia and Ghana. Her first book, "Honey from the Lion: An African Journey," is an autobiographical account of her time in Ghana.

In 2011, Belcher spent a year in Ethiopia researching hagiographies — biographies of saints — stored in monasteries to gain an understanding of Ethiopia's women saints. In this work she is collaborating with Selamawit Mecca (front left), an assistant professor of Ethiopian literature at Addis Ababa University.

This May your book "Abyssinia's Samuel Johnson: Ethiopian Thought in the Making of an English Author" was published by Oxford University Press. What was the connection between Ethiopia (then known as Abyssinia) and this famous 18th-century author — the father of the English dictionary and subject of the legendary biography by James Boswell?

One of the things Samuel Johnson did early in his literary life was to translate a 500-page Portuguese tome about the Ethiopians. I think he did the translation because he had read a book about the primitive Christians and at that time Europeans thought that the primitive — the "purest" — Christians were the Ethiopians, because they had been Christians longer than anyone else. This book was about something Johnson thought was horrible, about the Jesuits trying to convert the Ethiopians from their ancient form of Christianity to Roman Catholicism in the 17th century. But Johnson did this translation during a period of mental instability and it took peculiar hold of his imagination. In fact, I go so far as to say that he was possessed by it. For the rest of his life, Johnson wrote fictions about the Ethiopians that were partly animated by what the Ethiopians said about themselves. One of these was his most famous book, "The History of Rasselas, Prince of Abissinia," which was an imagined fiction about an Ethiopian philosopher prince who searches in vain for ways to live happily.

We always look at how Europe affected Africa; we very rarely look at how Africa affected Europe. So my book is trying to do the reverse of what is so commonly done by looking at the influence of Ethiopian thought on a canonical English author.

In your research on Johnson you made discoveries that led to your current work on some remarkable Ethiopian women, who were described as "diabolical" by the Portuguese Jesuits who were trying to convert Ethiopians until they were ousted in 1632. What was significant about these women?

As I was reading this tome Johnson translated, it was very interesting because women kept popping up in the text — royal Ethiopian women who refused to be Europeanized, who refused to convert to Roman Catholicism. So I began to read other texts around it and I found that the Jesuits who came to Ethiopia blamed the failure of Roman Catholicism in Ethiopia on these royal women. At first I thought this was just misogyny on the part of the Jesuits — blaming their own failure on women. But then I began to wonder if maybe they were right.

The more I read from the European sources and the Ethiopian sources the more I saw that, in fact, almost all the men of the court converted for reasons of state, to get arms from Europe, but almost all the women refused. And did so in very active ways, speaking out before the court, preaching against Roman Catholicism in the countryside, fomenting armed rebellions. The Ethiopian women saved the church, saved the nation. These women's resistance was very powerful. It is a story of how early Africans successfully resisted early forms of European colonialism, which people often assume always succeeded.

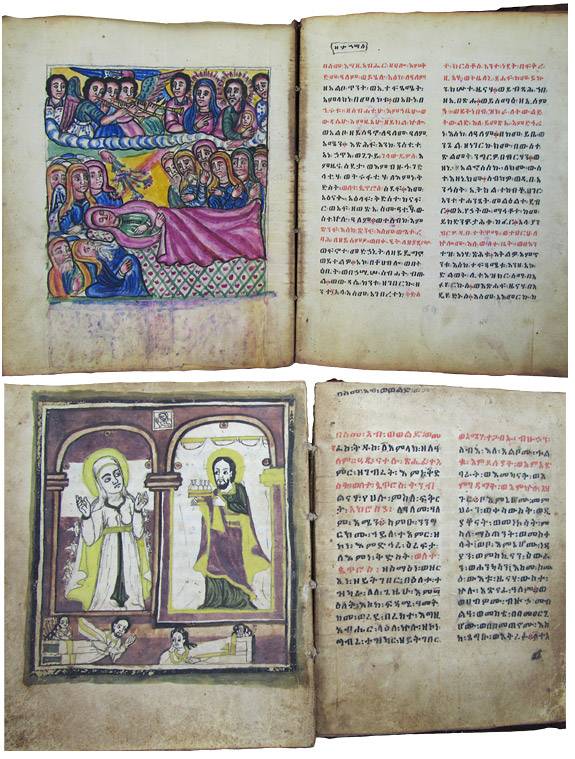

People also often assume that Africa has no texts before the 1950s. The fascinating thing about this period of history in Ethiopia is that we can compare two points of view, the Europeans' and the Ethiopians', because both wrote books about these experiences. The Ethiopians were writing historical chronicles and also hagiographies [biographies of saints], because these women who resisted became saints through their role. Ethiopia has about 200 indigenous saints, and most of them have hagiographies, and between eight and 14 of those, we're still figuring that out, are women. This is a large body of original early African literature that has gone almost entirely unstudied.

When visiting monasteries, some very remote, Belcher met nuns (above) and monks who continue to tell the stories of Ethiopia's saints.

One of these women who has captured your imagination, Walatta Petros, is recognized as a saint in the Ethiopian Orthodox Church. Who was she?

I am working with Michael Kleiner, a leading scholar of the ancient Ethiopian language Gə'əz, in translating a manuscript about Walatta Petros [1594-1643], who was one of these royal women who refused to convert. This book may be the first biography of an African woman written by Africans. It will be at least 175 pages in print form in the end, all about her and her life, and will be the first translation into English. I am also collaborating with Selamawit Mecca, an expert on Ethiopian female saints, who is an assistant professor of Ethiopian literature at Addis Ababa University.

We learn that Walatta Petros had an adoring father, that all of her three children died in infancy, that she left her husband because she wanted to become a nun, that her husband burned down a town to retrieve her, that she went back, left again, and started a series of religious communities of people who were refusing to convert. There are various points in the text when she is hauled in front of the court and asked why is she being so recalcitrant, why is she refusing to convert. She preaches about retaining the faith of their fathers and not turning to the "filthy faith of the foreigners."

We also learn lots about their daily lives, such as Walatta Petros getting angry with the other nuns for doing manicures instead of working.

People tend to think of Africa as the place where women have the least power. And yet it is my firm belief that women everywhere in every time have struggled for their rights and succeeded on some fronts and not on others. So I'm always looking for the story that goes against this narrative of Africa being particularly oppressive toward women. So the story of these very powerful Ethiopian women really captured my imagination.

Belcher's work focuses on the story of Walatta Petros, a royal woman known for her fiery resistance to Roman Catholicism in the 17th century, who is recognized as a saint in the Ethiopian Orthodox Church. In comparing manuscripts of Walatta Petros' story (such as those shown above), Belcher, working with Michael Kleiner, a scholar of the ancient Ethiopian language Gəʿəz, is hoping to publish the first biography of the saint's life in English.

During a Fulbright grant last year you did extensive research in Ethiopia on Walatta Petros and other female saints, including visiting monasteries to discover manuscripts for further study. What do you hope to gain from this work?

What happened in Ethiopia when I was there was that Selamawit and I managed to find other copies of Walatta Petros' story. By going to monasteries and doing a lot to get permission to photograph these handwritten parchment manuscripts and finding where they were, we now have a number of versions. This is really important because the first print edition in Gə'əz — and its Italian translation — is based on only one copy of the text. This means that parts of the text were confusing, probably due to scribal errors, and now, by comparing these different texts, we will be able to clarify a lot more. By doing that we may also be able to find out more information about who the author is.

With Selamawit I visited Walatta Petros' monastery, for which you have to travel for about an hour by motorboat across Lake Tana; it's very remote — no running water, no electricity. At this monastery there are quite a few manuscripts devoted to Walatta Petros.

You lived in Ethiopia as a young child. How does that experience resonate with you now?

My first memories are of Ethiopia. It was a completely magical place for a child that age. There was a castle in my back yard. There was a descendant of King David on the throne. My parents would point out that the way the oxen were threshing the grain was the way they did it in the Bible. It was like living in a book. And it fed my lifelong fascination with books.