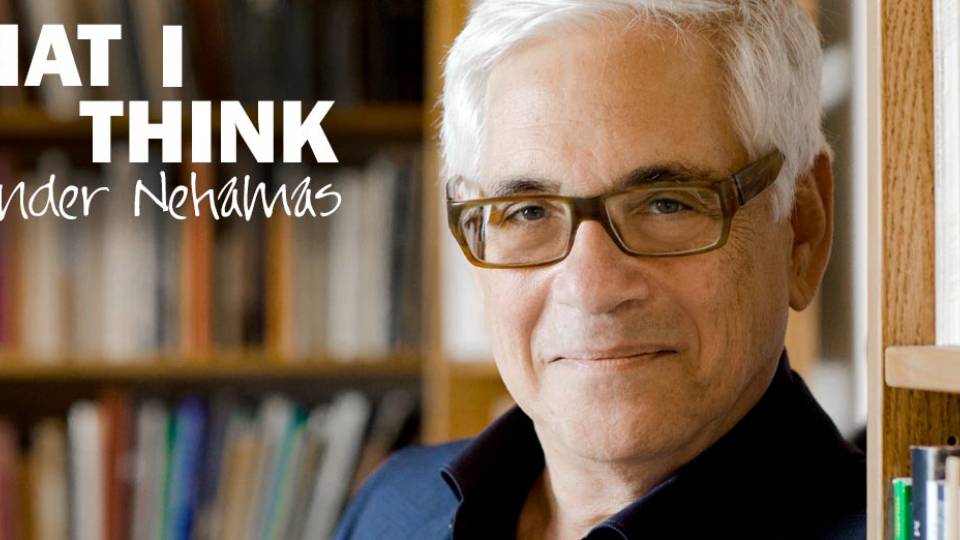

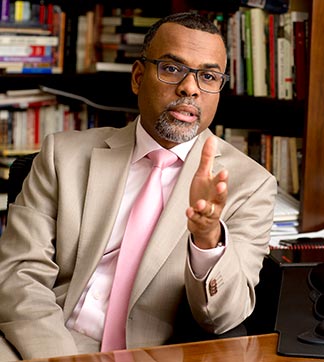

In musings drawn from an interview, Eddie Glaude Jr., the William S. Tod Professor of Religion and African American Studies and chair of the Department of African American Studies at Princeton University, reflects on his Southern childhood, race and identity, politics, teaching at Princeton, student protests, courage, democracy and more. Photo by Denise Applewhite, Office of Communications

Eddie Glaude Jr.(Link is external), the William S. Tod Professor of Religion(Link is external) and African American Studies(Link is external) and chair of the Department of African American Studies, has taught at Princeton since 2002. He was born in Moss Point, Mississippi, and grew up surrounded by his extended family, including great-grandparents on both sides, many of whom lived in nearby Pascagoula. He earned a Ph.D. in religion from Princeton, a master’s degree in African American studies from Temple University and a bachelor’s degree in political science from Morehouse College. This fall he is teaching the undergraduate course “Introduction to the Study of African American Cultural Practices” and the graduate course “Religion and the Tradition of Social Theory.” His latest book, “Democracy in Black: How Race Still Enslaves the American Soul,” will be published by Crown Books on Jan. 12.

These musings are drawn from an interview.

If I hear a blues track, it takes me back home. If I hear a song by Al Green or my favorite blues musician, Bobby “Blue” Bland, it takes me back to Moss Point. Every Saturday in my hometown, when I was growing up and to this day, it’s All Blues Day on the radio.

The radio is on all the time, because my mother says she doesn’t want the room to be silent. My oldest sister is severely disabled. My mother had German measles when she was pregnant. For 52 years, my mother has been taking care of my sister, and the radio’s always on, even though she [my sister] can’t hear or see or talk or walk.

I remember the Klan burning a cross at the fairground. My brother tells me that didn’t happen, but I remember it happening.

I grew up in a working-class family. My mother left school in the eighth grade, had her first baby. She worked in fast food restaurants for a while then got a job cleaning toilets at Ingalls Shipyard in Pascagoula. She then rose to the level of supervisor of the cleaning detail. My dad was the second African American postman hired by the post office in Pascagoula — my dad’s hometown, the hometown of [former Sen.] Trent Lott, and the place where William Faulkner had his honeymoon.

We were the third black family in the neighborhood when we moved from the east side of Moss Point to the west side — the white side. My dad saw he had precocious kids so he wanted to move. We were now middle class. The police drove by slowly as we were moving in. My dad dangled the keys and said, “Yes, I own it.”

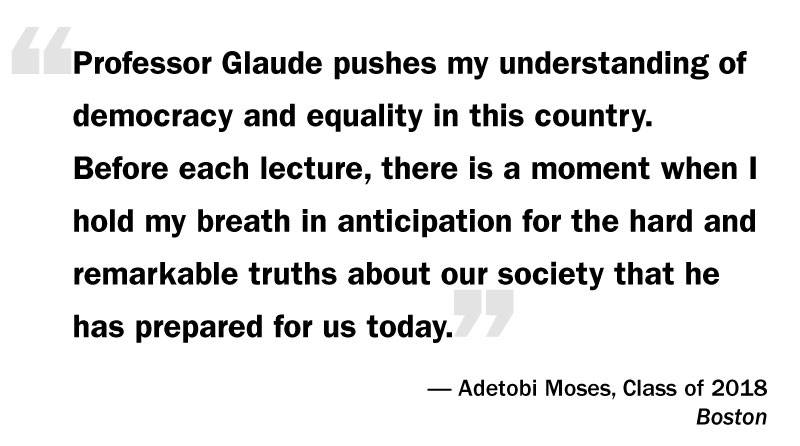

Glaude poses for a school photo in the first grade. (Photo courtesy of Eddie Glaude Jr.)

My earliest memory — or, as Toni Morrison would say, “rememory” — related to race is this: I was playing with those old hard Tonka trucks outside with my new neighbor. I was in second or third grade. We were putting dirt into the dump truck, and all of a sudden I heard his dad yell his name and tell him to stop playing with “that [racial slur].” I took my truck and walked inside and told my father what had just happened. I remember my dad just staring blankly and storming out of the house. I don’t know what he did, but that family moved. Eventually there was like a mass exodus in the neighborhood, people just started moving as more of “us” moved in.

My dad was all up in me. He was in the Navy, and served in Vietnam. He is a really intense guy. He yells, he gets angry, all of us were afraid of him. But everything I’ve done, who I am, is a reflection of the discipline of my father. He was an extraordinary influence on me.

My great-grandfather, Russell Wilson, was the gentlest human being I have ever met. He modeled how to be a man. He never raised his voice, I never saw him angry. He allowed me to have this space to absorb the lessons my dad was teaching me in his own way. My baseball coach revered my great-grandfather when he would come around. I found out later that when Coach was growing up, their family was so poor that my great-grandfather, who didn’t have much either, used to bring them food.

My great-grandmother, Ruby Wilson, cooked the best pinto beans on the planet. She would make this hoecake bread, a kind of biscuit, on the top of the stove in a cast iron skillet. We would eat it with sorghum syrup and the pinto beans, and you’d forget you didn’t have any meat. We would go over to their house and it would be just calm. Unadulterated love. It was just amazing.

I don’t watch a lot of television but I love watching “Big Bang Theory” — that’s a secret — because I’m a nerd. Although it’s a caricature of us, I enjoy it.

My favorite apps on my iPhone are Candy Crush — I’m at level 372, I think — and a DJ mixing app. My latest mixtape had Midnight, a reggae band from St. Croix; Bob Marley; and Burning Spear.

My son and my wife are constantly telling me to relax because I’m so intense. I am happiest when I am snuggled up with a novel. I’m in hog heaven. When they see me reading, [they know] I’m relaxed.

I can fry a mean chicken. I love to cook — when I can. Anything Southern. I learned how to make my mother’s classic crab meat dressing — it’s stuffing with crab meat in it, ’cause I’m from the coast and it gives it a wonderful taste. I bake sweet potato pies, I can make shrimp and grits, Charleston-style. Cooking is relaxing, too.

Glaude speaks with senior Yentli Soto-Albrecht following a lecture in the undergraduate course “Introduction to the Study of African American Cultural Practices” he is teaching this semester. (Photo by Denise Applewhite, Office of Communications)

I jumped out of high school after my junior year, but I had been elected the youth governor of the state of Mississippi. It was a huge deal that the youth of Mississippi had elected this black kid youth governor. I was part of the Mississippi delegation at the 1984 Democratic National Convention in San Francisco. I was sitting right there listening to the “Tale of Two Cities” speech by Mario Cuomo. I watched Jesse Jackson, Gary Hart, all those folks, all of that conflict, up close. I was on my way to college with the idea that I was going to major in political science, become a lawyer, then I was going to come back to Mississippi and run for office.

I walked into the dean of admission’s office at Morehouse College while attending a summer science program and said, “I’m going to convince you not to send me home.” And I walked out of Dean Hudson’s office with a scholarship — the same early admission program with which Martin Luther King Jr. and Maynard Jackson had been admitted.

At Morehouse, I had a conversion. I found a language for my dad’s anger and rage; I had a language for my own anger and rage. I was this black nationalist; this was my politics.

My life was the canvas to create. I was only 16 when I went to Morehouse. I tried on so many different things, trying to find who I felt comfortable being. Now, I’m someone who is trying desperately to step into who he takes himself to be and do what I have been called to do. I have a clear vision of what that is. It involves a way of being an intellectual, being in love with ideas, that has a bearing on the way the world is. So it’s not some narcissistic preoccupation, but to be in love with ideas with an aim to help make the world better.

Princeton is a liberal arts institution at heart. It’s on steroids, but it’s still a liberal arts institution.

If I could tell incoming freshmen one thing, it would be: Try on as many selves as you can.

I’m challenging my students to think about how fragile the American democratic project is, to understand the complexities of this fragile experiment from the vantage point of African Americans and to see that the complexity says something about who we are as Americans generally. African American culture and life offer an extraordinary lens for them to see, to understand and to imagine differently what this country can be.

From my students I learn how quickly time flies. One minute they’re freshmen and the next minute they’re seniors. They are so excited about learning. Even if you’re teaching the same material that you’ve taught for 10 years, the way a student enters it gives you life. They model how we ought to orient ourselves to the life of the mind more generally. Every occasion offers you an opportunity to learn and to grow. And in the classroom you see it every single day.

Glaude’s latest book, “Democracy in Black: How Race Still Enslaves the American Soul,” will be published by Crown Books on Jan. 12. (Photo courtesy of Crown Books)

I’m challenging my graduate students to understand themselves as scholars of religion. We’re introducing them to canonical text, reading together with these brilliant folks, settling down in these ideas, understanding how they might be useful to their own approach to the study of religion, because one day they will be teaching this course to their undergraduate or graduate students.

I’m hopeful that we are at a moment to really reach for a genuine democratic society — not just for African Americans but for the country in general. The contradictions are such now that if we don’t all hell will break loose. I can’t have any other faith other than in us. We will have to save the country.

I feel like I’ve made a contribution for the fourth grader who will end up coming to Princeton so many years from now. That the Center for African American Studies at Princeton is now the Department of African American Studies is huge(Link is external); that it happened when I was chair is really humbling. We’re preparing our students with the skill sets to go out and deal with and lead a diverse world.

I tell my students to cultivate self-care and to wrap themselves in love, but I’m not very good at it myself. I have some wonderful friends, and I have an amazing family, and they often protect me from myself.

My favorite place on the Princeton campus is the chapel. It gives one a sense of the expansiveness of the place. Yet, it allows you to think beyond the everyday demands of daily life at Princeton. And, of course, it doesn’t hurt that I was married in the chapel.

We named our son Langston Ellis — after Langston Hughes and Ralph Ellison. My wife [Winnifred Brown-Glaude, chair of African American studies at The College of New Jersey] and I said to him from the day he was born: Your name represents power. Walk the world in honor of your name.

In the eighth grade, he came home from school during Black History Month and said, “Dad, it’s like Martin Luther King Jr. is like the only black person who ever lived.” I said to myself, OK, this is good.

I have the most amazing colleagues on the planet. I can replenish — I can just go upstairs and talk with Imani Perry, go downstairs and talk with Ruha Benjamin or Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor. I can go across campus and bump into Jeff Stout — my former teacher who’s now my colleague. I can read a piece by Sean Wilentz in The New York Times while I’m working out, send him an email and then bump into him and say, let’s sit down and let’s argue about this. It’s really the vibrancy of the intellectual space and the intimacy of it and the intensity of it all.

The power of a liberal arts education is rooted in the claim that we’re all engaged in the art of living. A liberal arts education gives one the resources to think of oneself in the most expansive way.

Colleges and universities are the places where you cultivate the habits of courage or you learn the habits of cowardliness. When the students responded to the non-indictment of Darren Wilson and marched on Prospect Avenue, later organized a die-in response to all of the deaths at the hands of police, and finally sat in at Nassau Hall and in President Eisgruber’s office, I was so proud, smiling like the Cheshire Cat from ear to ear. They asserted a sense of possession of this institution, not that they should be thankful to be at Princeton, but to claim the University as their own, and I just love that. To force it to reach for its better angels.

Sometimes I speak my anger, I gotta give it voice; sometimes I don’t, so it just simmers; and sometimes the people around me experience it, the people that I love, and it’s unfair, but it’s exhausting. Sometimes I have a nice Irish whiskey with a good cigar.

From the very beginning democracy in this country has been distorted by our willingness to concede to the value gap — a belief that white people are valued more than others. My book “Democracy in Black” is my attempt to give voice to the context of the Black Lives Matter movement. The value gap is given life not by loud racists — it’s evidenced in our habits, the way we live our lives and the choices we make. To close the gap, we’re going to have to change how we view black people, which means we’re going to have to change how we view white people, and how we view what ultimately matters. The only way we’re going to do that is we have to be made uncomfortable. That’s the only way habits change. But, the great thing is that habits do change.

I’m a country boy from a small town who made it big, but it has nothing to do with the American dream. It’s nothing but blessings and grace, extraordinary opportunities and some folks who loved me in spite of me.

Try to do good in the little short time we’re here.

Glaude leads a discussion in a class precept in Stanhope Hall, home of the Department of African American Studies. (Photo by Denise Applewhite, Office of Communications)