Alexander Nehamas, the Edmund N. Carpenter II Class of 1943 Professor of Humanities and a professor of philosophy and comparative literature, has taught at Princeton since 1990. He was born in Athens and speaks Greek, English, French, German and Italian, and reads ancient Greek and Latin. He has published and lectured widely on topics spanning classical philosophy, philosophy of art, literary theory, friendship, popular culture and television. Nehamas earned a Ph.D. in philosophy from Princeton and a bachelor's degree from Swarthmore College. This fall, he is teaching the undergraduate course "Nietzsche." His latest book, "On Friendship," is forthcoming from Basic Books in April 2016.

These musings are drawn from an interview with Nehamas and a conversation at the dinner following the annual Belknap Lecture sponsored by the Council of the Humanities.

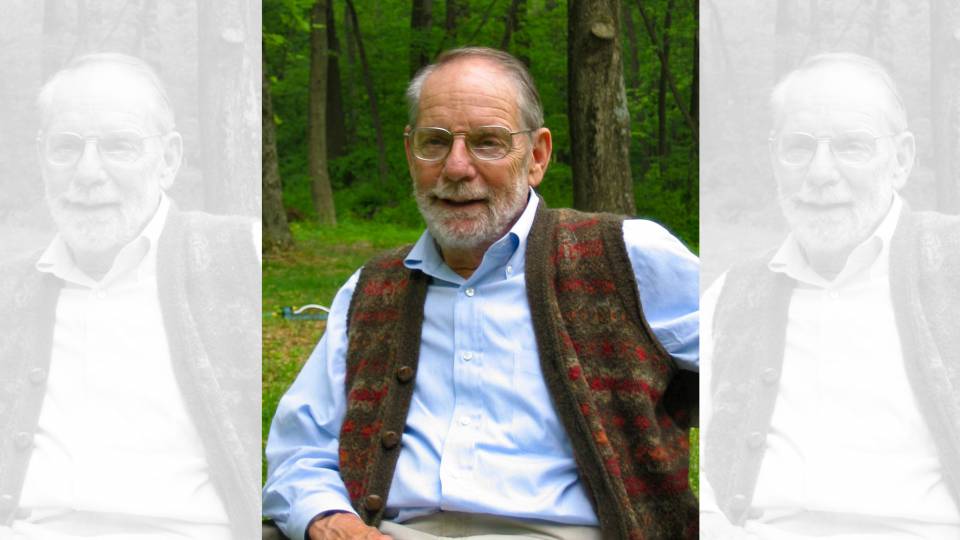

Alexander Nehamas, the Edmund N. Carpenter II Class of 1943 Professor of Humanities and a professor of philosophy and comparative literature at Princeton, has published and lectured widely on topics ranging from classical philosophy to popular culture. In musings drawn from two conversations, Nehamas reflects on Nietzsche, teaching at Princeton, television, beauty, opera, happiness, what makes a good life and more. (Photo by Denise Applewhite, Office of Communications)

I was brought up in the center of Athens but my parents sent me to boarding school only five miles away when I was 8 until age 18.

If I ever wrote a memoir, I'd mention the advice of a teacher of Greek. When I was 14, he said: "Never trust your first impression of a text. You will always find more in it if you keep at it." I still practice it. I would give the same advice to students.

My interest in philosophy started in high school with a copy of Spinoza's "Ethics," which is written in Latin with a Greek translation on facing pages. I couldn't understand the Latin or the Greek. I said: "Something that I don't understand completely must be very deep. That's what I'm going to do."

I went to college with the idea that I was going to join many Greeks by becoming a shipowner and then retire early and do philosophy. When I was growing up in the 1960s, Greece became famous for shipowning — Aristotle Onassis and Stavros Niarchos and all those big names. At Swarthmore, I majored in economics and philosophy. I didn't like economics very much, but even more, economics didn't like me.

When my son was very young, he asked me, "What do you do when you do philosophy?" I said, "Well, you think about the most important things in the world." And he said, "Like soccer?"

Nehamas' latest book, "On Friendship," is forthcoming from Basic Books in April 2016. (Photo courtesy of Basic Books)

When I first came to America I thought that only stupid people watched television. Then I ended up liking it. In 1983, I sublet a place that had a big color TV. I was writing a book, and by the evening I was usually exhausted, so I started watching a serious amount of TV. I said to myself, "If I don't make anything out of all this watching that I've done, I will have wasted a large part of my life."

The first thing I did was connect the criticisms of TV with Plato's criticism of poetry in "The Republic" because they are very similar. Plato outlaws dramatic and epic poetry from his ideal city for three reasons: it conflates the authentic and the fake; it's only good for representing sex and violence; and it perverts and destroys the life of those who are exposed to it. It's the mother of all arguments against popular culture — which is what Greek tragedy was, in many respects, at the time.

When the novel came about in the 18th century, it was hugely criticized. The same thing happened with photography, to cinema, to jazz — all those things started out as popular arts that were looked down upon by the higher establishment. But as we get farther from them and we no longer see them as direct representations of the world, we realize that there is art in what they have to offer us. It takes a while.

My favorite TV show is "St. Elsewhere." Any time you have 144 hours, I'll give you the discs. I have the whole thing.

I love "Game of Thrones." I also read the books. It's extremely well acted, it's very beautifully produced, it has everything — personal relationships, the fighting scenes are interesting, the diplomacy scenes are interesting. It's sexually a bit violent for me, but I find it very difficult to apply moral criteria in discussing art.

No man has ever worn a suit as well as Cary Grant. My love of style came from my parents — and Cary Grant.

Nehamas' love of reading spans philosophy to literature to whodunnits. At home, his books are shelved alphabetically by author. Above is a self-composed shelf of his favorite philosophical and literary works. (Photo by Alexander Nehamas)Click to enlarge.

Feeling happy is not nearly as important as accomplishing something in your life. Nietzsche wrote: "What matters my happiness? What matters to me is my work." Happiness as I see it is not only the feeling of pleasure with yourself or with life, it's also the sense that you have actually accomplished something worthwhile.

I am challenging my students to think about what makes a good life. Nietzsche was thought to have a very bad life because he was completely ignored, he was very sick most of his life, he had continuous migraines, he never found a woman he could marry, he was in love with a woman but she wasn't interested in him, he had very few friends and had not very much money. So people say, his work is great but his life is terrible. We define the life as everything but the work — and I think that's a really terrible mistake. But if you include in the life writing all these magnificent books and having all those incredible ideas, is that a bad life? I think that in a way is what happiness may be. Feeling "that's me" in your work, I think that's one of the greatest feelings you can have — ever.

I am also challenging my students to think about what they do for a living. You shouldn't do something primarily as a means to something else, for example, you shouldn't do something just as a means to make money. You should do something because you love it. If it's a kind of thing that brings you money, fine. But to think of what you'll spend most of your life doing as only a means for something else I think is a very demeaning way to live.

I'm very good at dancing the cha-cha-cha. I learned it in high school from a record that had the steps on the back that told you how to move your feet. I'm also good at pingpong.

You get three levels of wonderful stimulation by working at Princeton: You get it from the undergraduate students, you get it from your graduate students, and you get it from your colleagues. Princeton's size is ideal for close contacts with all those groups, not only in your own department but if you're interested you can meet all kinds of people from everywhere, whether it's engineering or psychology or mathematics or English or comp lit.

The questions that undergraduates ask you can be fantastic. They're really trying to learn how to live. It's a terrific responsibility. I don't know that I can actually show them how to live, I don't think anyone can show people how to live. The best we can do is give them an example of how one can live. Each one has to figure that out by himself. That's both a Socratic view and a Nietzschean view; it has to come from within.

My secret vices are impulse buying and De Lorenzo's pizza in Robbinsville [New Jersey].

What a friend should do is give the other person an opportunity to become themselves. For example, if you're making a big decision, friends can help you articulate what it is that you really want to do.

Nehamas and John Cooper, the Henry Putnam University Professor of Philosophy — who have been friends for 44 years — enjoy a walk on campus. (Photos by Denise Applewhite, Office of Communications)

My best friend at Princeton is John Cooper [the Henry Putnam University Professor of Philosophy] — we've been friends for 44 years. Few people can compare to him when it comes to interpreting a text. On an intellectual level, he showed me how to be a better reader than I was, how to try to hold myself to a higher standard of what counts as understanding something and having an idea. Not to go on talking without knowing what we're saying, which is something we all do, unfortunately. I learned a lot about friendship, family and life from him.

There is a deep common element behind finding a work of art beautiful, loving a person and being a friend. In all three cases, your feelings for the object or for the person are open-ended: you think that you haven't found out everything about that person or that work or art; it's this idea that there's more to see, there's more to understand, there's more to love here.

Manet's "Olympia" is a piece of art that takes my breath away. It is an amazing thing. I love, for example, that the figure is both vulnerable and very strong. I enjoy very much the fact that you can't tell a story of what's happening in the painting [which depicts a nude courtesan lying on a bed and a black servant]; nobody has been able to tell a story. When I was in Paris in 2014 to speak at the Princeton-Fung Global Forum, I went to see "Olympia" and it was like seeing an old friend. The painting was the topic of a series of lectures I gave at Yale in 2001, and the book "Only a Promise of Happiness: The Place of Beauty in a World of Art" that came out of them, but I hadn't thought seriously about the painting since then. When I saw it again, I realized that I didn't understand something about the picture, something I hadn't noticed before. She is holding a kind of silk coverlet, her hand towards the floor and you can't tell if she's about to cover herself with it or if she's just uncovered herself. The moment that I saw there was something else to learn here, something else to know, my love was rekindled. I kept thinking about her the way you keep thinking about a person you have a crush on.

Beauty is an indispensable part of human life. A beautiful object — say, a work of art that you actually find beautiful — represents an accomplishment on the part of its maker. You love and admire not just the work itself but the accomplishment it represents, and that can move you to try to accomplish something worthwhile yourself. Beauty is always an inspiration.

Philosophy and the humanities are extremely important. You learn about how people have lived, what people have believed, how they organized their life and society. Your horizons are broadened. But in fact what it does is it makes you a more interesting person, that is, someone who is not like everybody else.

I like opera, and I wanted my son to like it. We took him to the "The Barber of Seville" at the Metropolitan Opera. There's a great aria that the heroine sings early on and it was the debut of Jennifer Larmore, who is a great mezzo, and everybody stood up and applauded her. My son turns to me and says, "She's the best I've heard in years." He then wrote her a letter: "Dear Miss Larmore, You're the best I've heard in years. Love, Nicholas, 5 and a half years old."

Proust is like the love of my life. But I also love Ian Rankin, who writes what is called "tartan noir" — a whole genre of Scots who are writing mystery novels. I love whodunnits.

If I could spend a summer with one person — well, there would be two. Socrates because I would love to argue with him and figure out exactly what motivated him in the full knowledge that I will never understand him. Montaigne because I think he would be just about as engaging and broad-minded and compassionate as almost anyone else I know.