Amaney Jamal, the Edwards S. Sanford Professor of Politics and director of the Mamdouha S. Bobst Center for Peace and Justice, has taught at Princeton since 2003. Jamal was born in Oakland, California, and lived in Modesto, California, as a child. At age 10, her parents decided the family should move to Ramallah, in the Israeli-occupied West Bank, to learn more about their culture and their religion, Islam. Jamal returned to the United States for college.

She earned her undergraduate degree from the University of California-Los Angeles and her Ph.D. from the University of Michigan. She taught at Columbia University before arriving at Princeton. Her most recent book, "Of Empires and Citizens: Pro-American Democracy or No Democracy at All," was published in 2012 by Princeton University Press.

She teaches on topics including politics of the Middle East, democracy in the Middle East, gender and Islam, and comparative politics. She is also principal investigator for the Arab Barometer project, which measures public opinion in the Arab world.

These musings are drawn from an interview.

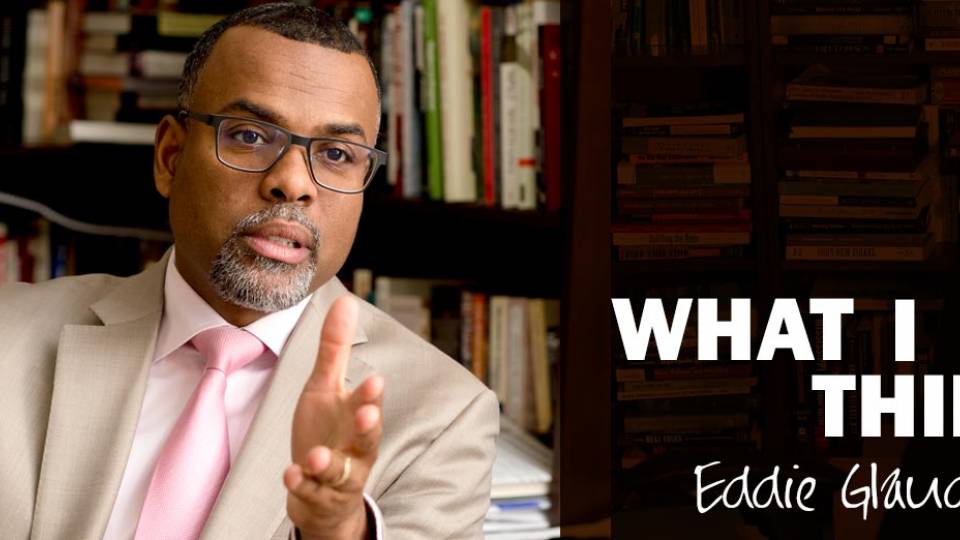

Amaney Jamal, the Edward S. Sanford Professor of Politics at Princeton University, teaches on topics including politics of the Middle East, democracy in the Middle East, gender and Islam, and comparative politics. (Artwork by Matilda Luk, Office of Communications)

When I think about Modesto, it's California, warm weather, baseball, "Star Wars," just like an all-American kid.

My siblings and I had never been to the Middle East. We knew we were of Arab background because we spoke Arabic at home, but we didn't understand what the Middle East was like. The only portrayals I had seen of the Middle East were in cartoons.

Today, American culture is very present in the Middle East in ways it wasn't in the 1980s. Pizza? What's that? Hamburger? People would laugh. There was no understanding. There was this feeling or this worry that I had been dispossessed of something I had grown up with.

I went to an English-speaking school, the Friends Quaker school in Ramallah. There I met a lot of other students who were in my situation, who had been in the U.S. and had gone home to learn the language, learn the culture, appreciate the history and such. That became my network.

The transition was hard. But then when I was 13, we came back for summer break in the United States. It was a great summer break, but toward the end, I found myself really looking forward to going back to Ramallah.

My parents were really invested in moving us back to Palestine. I think at the end they were very happy. We became cognizant of our identities as Arabs, Muslims and Palestinians. In a sense, we became hyphenated Americans.

During the first Intifada, Israel shut down all institutions of education. When that decision came down, I was about halfway through my senior year of high school. For the first few weeks we sat home, we played cards. We had friends over. It was fun. But then it dawned on us … that we're not going to graduate from high school.

The teachers started organizing classes in their houses, but you'd have to go through checkpoints to get to the teachers' homes. If the Israelis stopped you, you'd say you're going to go hang out or going to eat. That's how I graduated from high school.

Even our high school graduation was a graduation ceremony held in secret.

I am an American citizen. I didn't really have to stay in Ramallah. At that point, my mother and my father had said we should go back to the United States. My sister and I, the older siblings, said we felt like we were obligated to stick it out.

When you re-enter life in the United States, no one even comprehends what you've been through. That adjustment phase was very difficult for me. It's when I discovered my spiritual side. When you walk on campus, you're not worried about anybody stopping you or searching you or asking you what you're doing. Every time I'd be walking into my classes, it was such a joy to be able to walk on a campus and not worry. I spent a lot of time thinking about that.

Jamal's most recent book, "Of Empires and Citizens: Pro-American Democracy or No Democracy at All," was published in 2012 by Princeton University Press. (Photo by Denise Applewhite, Office of Communications)

My parents thought I would go to medical school. And I set out to do a science track, a premed track. I was doing fine, but I was just so bored and frustrated by the labs. Because you have to take electives, I was taking electives in political science and history and I was loving those courses.

One day the professor in a political science class comes in and says: "I don't know this student but this is the second time the student has written an A-plus paper and I've never had a student get two consecutive A-plus papers. I need to meet this student." He told me to stand up, but I was embarrassed so I just raised my hand. I told myself I was going to take more of these courses. I did really well, and I finally converted over to political science.

It's not until very recently, after I got tenure, that my mother stopped saying I should have gone to medical school.

I suppose what drew me to political science as a field and to the field of education was I found myself educating anyway just by default of being who I was.

I've been doing this work, interviews and work in political science for some time now. I realized early on that there are these solid misconceptions in the United States of the Middle East, of Arabs, of Muslims — that whole category of "other." You come back here and you realize when people in class are talking about that "other" it's really you.

People will say, oh, you're different. You're not "that kind of Muslim." You're a "moderate" Muslim. That exemplifies the divide.

There's always this feeling that you're straddling two different cultures, and for one you're always representing the other. In a way you feel like you're always on the fringes of both cultures but you're never fully accepted in either.

In the West, I think there's a lot of fear and suspicion. And part of that fear and suspicion is driven by real-world events and a lot of it is driven by what is really the fear of the unknown. On the Muslim or Eastern side, there's a misconception that the West is invested in subordinating Islam and keeping it quote-unquote as primitive. When you bring them together they have that clashing effect, like trying to bring a negative magnet and a negative magnet together. It pushes them farther apart.

I do a lot of surveys on Arab public opinion, but I want to make sure why people are answering the way they answer. Sometimes, I will be in a taxi and I'll talk to the taxi driver. Sometimes, I'll walk into a coffee shop and there will be a couple of men. I ask them for permission to sit down and talk to them. There's never a shortage of people who want to talk to you.

Go onto an Arabic satellite channel and watch the equivalent of Oprah in the Middle East. The people on these shows have the same concerns that the people going to Dr. Phil have. When people understand that Muslims or Arabs worry about their kids the way we "Americans" worry about our kids, that their kids don't go to sleep at bedtime either, these commonalities overwhelm the differences.

When I teach my politics in the Middle East course, what I say is that we're going to deconstruct the misconceptions you have of the other, whoever the other is. Every student comes in with their own image of the other, whether they're white or black or Latino or Muslim or Arab or Christian or Jewish. We're just going to break this down. In a sense, yes, we learn about the Middle East, but we also learn how to engage with one another much more effectively.

The best feeling always is when you've done all the fieldwork, and you've done the designs and finally you get that dataset and it's ready to analyze. That's the happiest moment. It's like a little kid in a candy store.

The most frustrating feeling is all the problems that happen before you get that dataset.

As an academic, if I had no constraints, I'd love to spend a month in each country in the Middle East, being able to set up shop in an apartment — do research and find time to write with no responsibilities at all and not worry that I've forgotten to respond to somebody's email.

When I appear in the media to talk about ISIS and the Middle East and the Arab-Israeli conflict, I don't get a lot of emails about that. I went on the Melissa Harris-Perry show and talked about "Star Wars," and everybody was really amazed. So many young women emailed me and said it was great to see a Muslim woman talk about "normal" things. I guess it was surprising to a lot of people that I'm actually a "Star Wars" fan.

A place I love going to is Firestone Library. When I get an afternoon off, I'll go to the library and it's my secret treat. I'll hide out in the library and just look at books and think about ideas. I feel like it's this place where you work out some of your ideas. Somehow it happens in the library better than other places.

If you don't experience failure, you won't be able to experience success. It's advice I consistently got both from mentors in the United States and in the Middle East. It's always kept me going and allowed me to persevere.

I'm proud of my children. I'm really proud of this institution. I'm proud of my students when they go out into the world. There's a lot to be proud of.