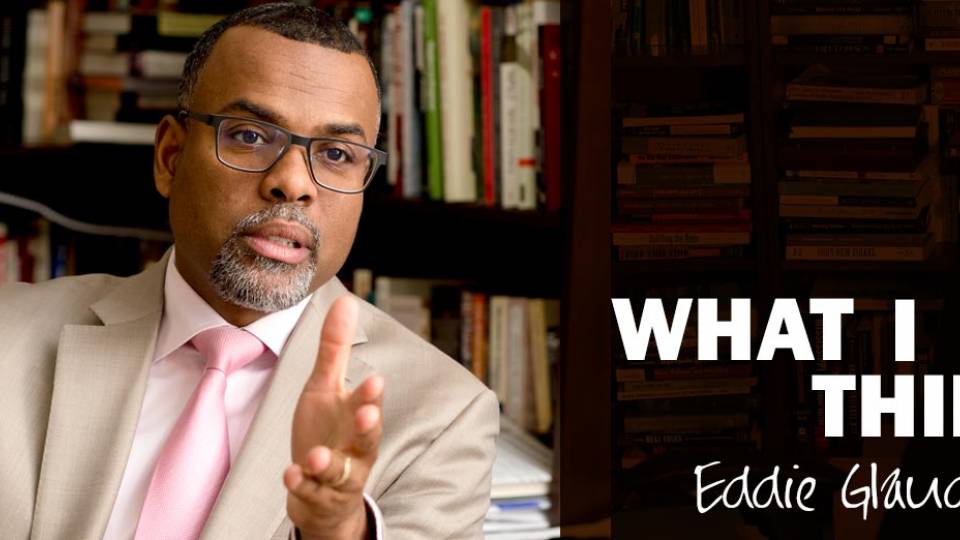

Imani Perry, a professor of African American studies at Princeton, first appeared in print at age 3 in the Birmingham (Alabama) News in a photo of her and her parents at a protest against police brutality. She has published widely on topics ranging from racial inequality to hip-hop and is active across various media. She earned a Ph.D. from Harvard University, a J.D. from Harvard Law School and a bachelor's degree from Yale University. This fall, she is teaching "Model Memoirs: The Life Stories of International Fashion Models" and "Diversity in Black America."

These musings are drawn from two interviews with Perry.

I am happiest reading with my kids. I like reading Buddhist parables to them and then having discussions about them.

My secret vices are Uncle Al's banana creme cookies and pineapple soda. I have to order Uncle Al's from Alabama. The soda you can get at any little store that serves immigrant communities.

As we drove to school recently I told my sons about the non-indictment for the officer who killed Eric Garner, the manslaughter charge being dropped for those who killed 7-year old Aiyana Stanley-Jones, and we had been talking about Ferguson and the killing of Mike Brown. I told them that we are entering a period of history in which we are going to have to organize, to protest, to speak out, to fight back against our dehumanization and that that's not always an easy thing to do. But we're worth it, our people are worth it.

Princeton is a place where I have felt that my voice matters. That's an unusual experience for women, an unusual experience for black women, to feel as though when you speak people listen and care what you have to say and you're not fighting to be heard.

The songs that make me weep are Al Jarreau's "Glow," Esther Satterfield's "Look to the Children" and Stevie Wonder's "I Was Made to Love Her."

My grandmother took care of two white children, and we all played together. But when their parents came to pick them up, we would move behind the door and peek through. No one told us to do this, race codes are often learned tacitly.

Protest was a huge part of my early childhood. I remember asking my parents one year, are we going to go celebrate the Fourth of July? They said no, black people were still enslaved then. And then I said, well, could we have a demonstration instead.

My family is filled with people who were known for being smart and know-it-alls, lots of valedictorians, but also creative. I was born into a black Southern Catholic family. But my adoptive father, who passed away in 2014, was Jewish from Brooklyn.

I talk about race with my sons all the time. The approach that I've always taken is that you lead with the joyful instead of the terrifying. I say, look, people from where your ancestors are from transformed the world, transformed the country, they made it more just. I want them to have a sense not just of racial inequality in terms of them being vulnerable but them standing in a tradition of extraordinary courage.

My grandmother did not finish high school but singlehandedly sent all 12 of her children to college. She used to always say, "You weren't born to live on flowerbeds of ease." I remember she read the entire newspaper and cooked us a hot breakfast every morning — grits and toast with a bright yellow patch of butter and sausage.

Books are everything to me. When I was young, books provided comfort and security and also a space for imagination. When my mother was busy writing her doctoral dissertation, I always had a book with me. I read all day long.

I'm working on a new book on gender theory and the "feminist analytic," how to analyze the world through a feminist lens, in light of economic and geopolitical shifts and the way that we live in this hyper-media environment. I'm also working on another book — a cultural history of the song "Lift Ev'ry Voice and Sing," which is known as the black national anthem.

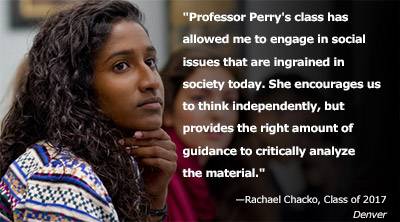

The gift of teaching at Princeton has a lot of parts to it. The students are serious students; they approach their work with a kind of integrity. That means that we can go pretty deep with the material, and while 18-23 year-olds are largely formed it's also this incredibly exciting time of growth. They're expanding themselves.

I'm most afraid of failing my children. That's the only thing that keeps me up at night, worrying about anything happening to them or me.

Math is so elegant. It's so beautiful. As an undergraduate at Yale, I began as a math major but switched to literature and American studies. As a scholar, however, everything I do when I analyze anything is mathematically oriented. Every time I write about literature or about social phenomena, I'm always looking for patterns, repetition, structure, the size relationship between things.

There's so much about human resilience in the story of race in America. The terrible parts of race are so apparent, from enslavement to lynching to segregation. The beautiful part is more elusive but is as important to talk about: how black people developed resilience, creativity, kinship structures, a new culture after their culture is lost.

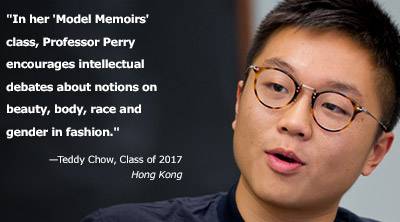

The "Model Memoirs" class I'm teaching this semester is an occasion to use the form of the memoir as a means of thinking about fashion both in terms of the transnational experiences of the models — who are crossing class lines and have very interesting life stories — and as an industry: the production of images, sexism, racial inequality, conceptions of beauty, economics and the politics of gender.

My interest in fashion came from my grandmother and mother. For them, attentiveness to grooming, particularly coming out of the segregated South, had a lot to do with self-respect and self-care. My mom made her own sewing patterns. I used to sew too, and now I crochet. By age 12, I was purchasing Elle magazine, partly because it was amazing to me to see models in those pages who were skinny young black women like me wearing interesting, weird clothes.

My son Issa watches every episode of "Project Runway" with me. Anytime there's anything revealing, he says, "Oh, no, no, no, that is too inappropriate." It's interesting that he has a kind of conservatism towards fashion as an 8-year-old. He prefers to wear basketball jerseys and sweats. My older son Freeman wears fedoras and oxford shirts. They come by it honestly.

The thing about Princeton is that it's really a cross-section not just of the country but the world. The variety of experiences that the students bring to bear, what they've read, what they've thought about, where they've been, opens the door to really rich conversations. Race is a hard topic to broach in class, and they are so respectful of each other as they're discussing it. There are lots of vulnerable moments when you're having these conversations.

If I could spend the summer with a historical figure, it would be Frederick Douglass because he's influenced so much of what I think. I think of him as the author of progressive constitutional interpretation. Not only was he enslaved, and then became an orator and then a leading intellectual, and then he said, "I'm a citizen and here's how we ought to interpret the Constitution."

People who know me professionally probably would be surprised that I like to socialize and celebrate — I dance well, and I can recite lots of hip-hop lyrics.

Perry (standing) leads a discussion in the "Model Memoirs" class she is teaching this semester — in which students are reading about models' transnational experiences and examining issues within the fashion industry such as racial inequality and the politics of gender.