In spring 2021, visual artist and Princeton University Hodder Fellow Mario Moore joined Imani Perry, the Hughes-Rogers Professor of African American Studies, in teaching a Princeton Atelier course, “Visualizing the Battle Cry,” to give voice to Black Civil war soldiers through visual and sonic projects.

Before the Jan. 6, 2021 assault on the U.S. Capitol, before the COVID-19 pandemic, before the death of George Floyd and the resulting Black Lives Matter protests and activism, visual artist and Princeton University Hodder Fellow Mario Moore was mulling an idea tying America’s past to its present.

Mario Moore

“I was thinking about the Civil War and considering its historical impacts and its relationship to what was happening at that moment because I started to see things that were very similar — histories that I felt like America as a nation wasn’t really dealing with,” he said.

Moore became especially curious about the experiences of Black Civil War soldiers, men who bravely fought for a country that initially refused them citizenship and whose voices are largely missing from the historical record.

White Confederate soldiers are known for their “rebel yell,” which led Moore to wonder what might have been the sound of the Black man’s battle cry.

“I immediately started thinking about hip hop,” he said. “I started thinking about Kendrick Lamar. I started thinking about rappers that are dealing with similar issues as far as what has happened to Black people in America. And I was like, this is really interesting.”

Moore’s prescient vision of the links between the plight of Black soldiers during the Civil War and the state of racial justice and Black culture in modern-day America became the inspiration for a Princeton Atelier course this past spring titled “Visualizing the Battle Cry.”

The Princeton Atelier, based in the Lewis Center for the Arts, brings together professional artists from different disciplines to create new works with students in the context of a semester-long course. These courses are intentionally small, allowing the participants to delve fully into the intensive collaborations of the artmaking experience.

Moore asked Imani Perry, the Hughes-Rogers Professor of African American Studies, to join him in developing an original project connecting their reimagined call of the Black Civil War soldier with modern hip hop, and to engage students in contemplating the historic and cultural through lines between these eras.

Imani Perry

Perry, a literary and cultural studies scholar and the author of six books, including “Prophets of the Hood: Politics and Poetics in Hip Hop,” did not hesitate to say yes. “I am profoundly moved and inspired intellectually by Mario’s work and the way he brings us into histories,” she said. “I also love speculative work — how you read into the past with all these clues — because much is not recorded in Black history, in particular. So it was a thrilling concept to me from the beginning.”

As a 2018-19 Hodder Fellow, Moore created “The Work of Several Lifetimes,” an exhibition of etchings, drawings and large-scale paintings of Black men and women who work at or around Princeton’s campus in blue-collar jobs. Several pieces have become a permanent part of the Princeton University Art Museum’s collection.

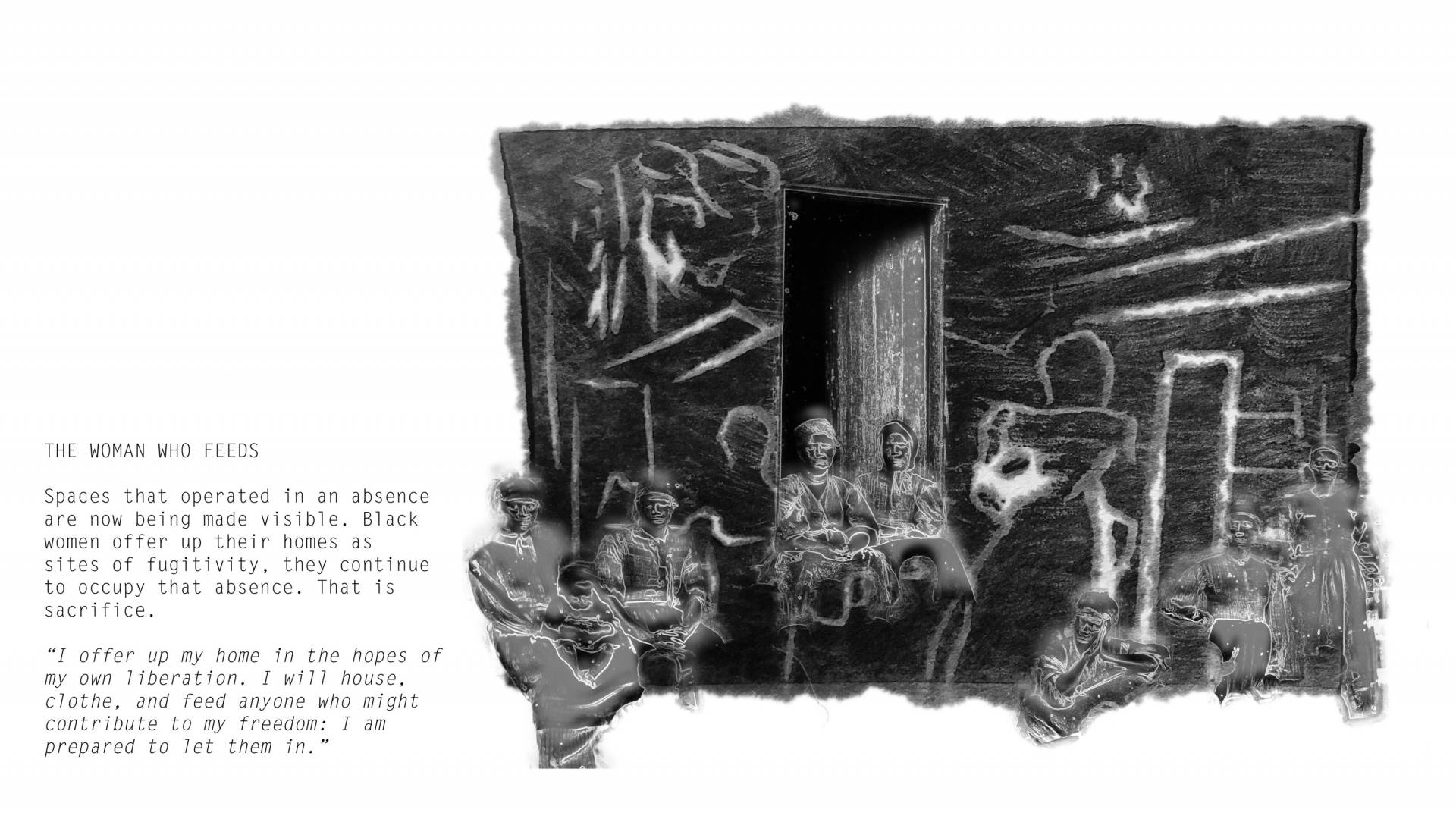

In the Atelier course, Moore, Perry and their students undertook a similar exploration, imagining and bringing to the fore Black lives that have long been hidden, unrecognized, unseen and unheard. They used the available historical record to envision the lives of Black Civil War soldiers, also drawing creative inspiration from the visual aesthetics of 19th-century posters and media — Harper’s Weekly, in particular — and from the substance and soundscape offered by hip hop.

Each week Moore and Perry introduced the students to a variety of materials — documents, images, audio clips, movies — all in the service of finding a voice for the soldiers, and giving it sound, texture and meaning.

The students listened to field hollers, slave spirituals, early gospel and prison work songs. They watched Zora Neale Hurston’s films documenting Black workaday life in Florida in the 1920s. They read the poetry of Sterling Brown and listened to performances by Gil Scott-Heron, where one can hear the coming of hip hop.

Moore and Perry also had the students move backward and forward in time, listening to contemporary artists including Marvin Gaye, Aretha Franklin and James Brown, then reaching back to early blues, for instance, for comparison. Perry said it allowed the students to hear what sounds have been consistent over time.

“There’s the historical trajectory of music, of sound, of language, because it’s so heavily tied to the language patterns, and then there’s the way it recycles,” she said. “When you have a cultural tradition, people go and pick things back up again.”

The students were asked to keep a sketchbook and complete five sketches a week exploring the presented materials and ideas.

“So much of their education is about learning information and learning methods and analyzing,” Perry said, “but there’s always this important part of developing intellectually which is imagining and creating.”

Getting ‘vulnerable with ideas’

Many of the 12 students who joined the course had no previous art experience and came from a range of concentrations including engineering, molecular biology, architecture and the School of Public and International Affairs (SPIA).

Their first assignment was intended as an ice breaker, where they shared a favorite song and a visual expressing how the song made them feel.

Moore said it was important that the students felt comfortable opening up to him and Perry — and also to one another — to form a true, professional collaborative setting.

“Ultimately, that’s what the Atelier is all about,” Moore said. “We have to share our ideas and have this sense of collaboration for us to really pull forward with a final project.”

The students said they appreciated Moore and Perry creating space where they could be vulnerable with their ideas.

“It was definitely nerve-wracking at first, but I think the fact that most of us don’t have any artistic experience made it safe and even fun,” said Zack Kurtovich, who graduated from Princeton in May. “Beyond that, I think professors Moore and Perry were just really open to anything in terms of which creative direction you wanted to go.”

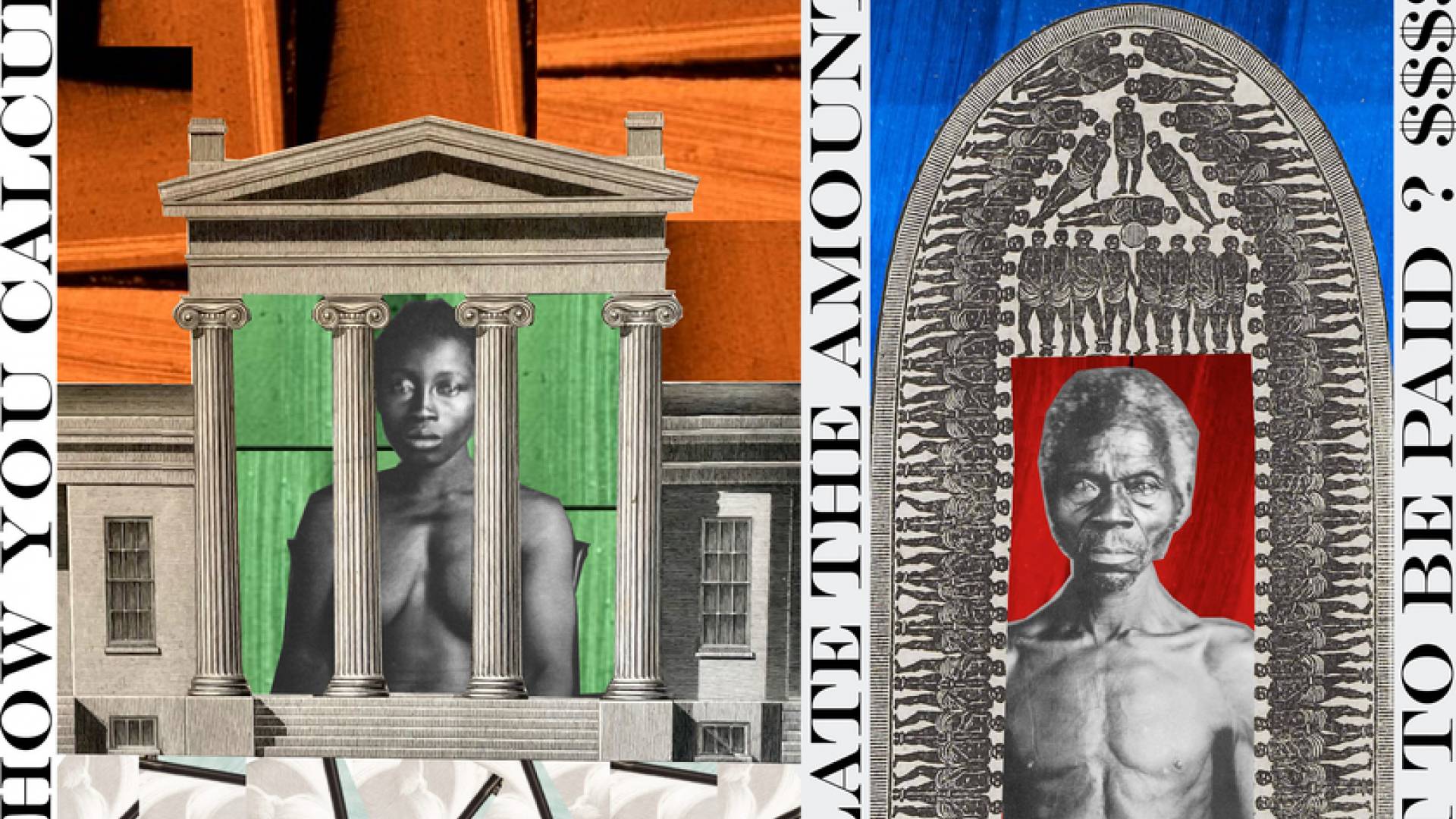

The students’ second assignment leaned into the reconceptualization of history — a kind of remixing. They were asked to choose an image from the Civil War era related to Black soldiers or to the racial dynamics during that time, and to connect it to the modern day.

“I really enjoyed the conversation we had about how loaded it can be to select an image and engage yourself within this discourse, because we’re not apolitical bodies,” said Taka Tachibe, a graduate student in the School of Architecture. “We’re factoring in, somehow, to a history that’s well established. I think it’s really sensitive, and it’s been amazing to see how sensitive the conversations have been.”

Moore said the final project was left open to the students, allowing them to engage the course theme through visual or sonic language, or through a combination of media.

“It was my hope that in the beginning, as we were giving them this history, that when Imani and I started our project and our project started to grow, that they would follow along with their own ideas and also pull together different histories themselves,” Moore said.

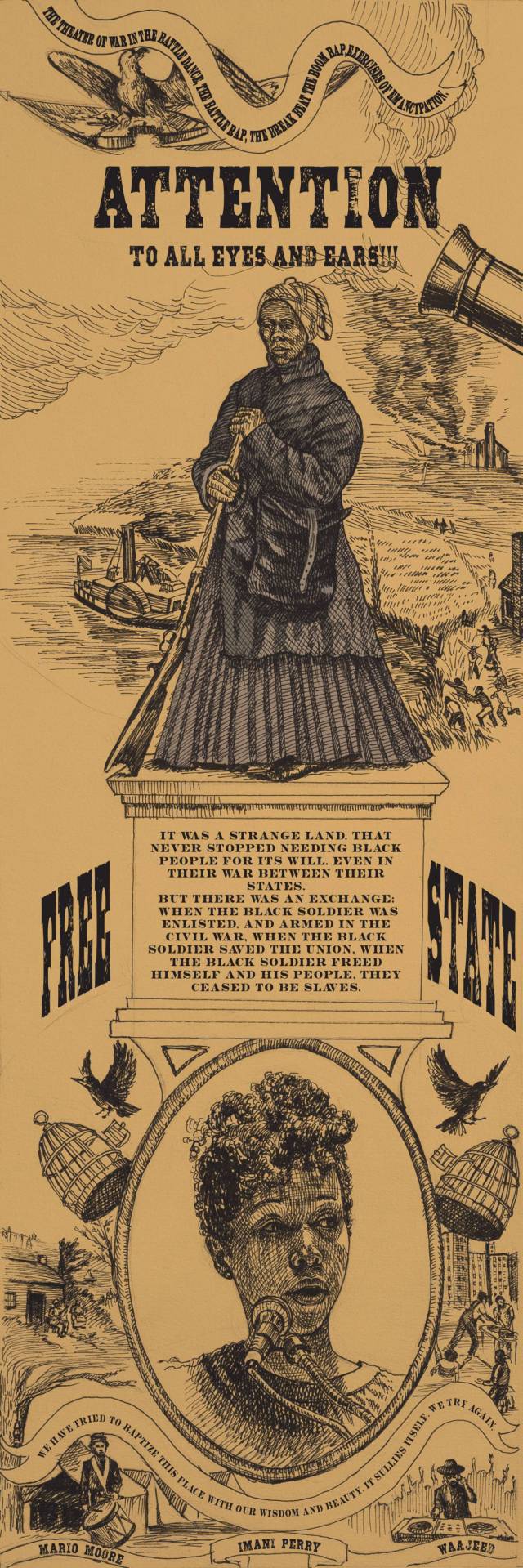

For their collaborative work, Moore and Perry are releasing a spoken-word album this fall. Moore created the cover art (pictured), which also will appear as a 9-foot banner in an upcoming solo art exhibition.

Continuing to confront history through a new spoken-word album

For their collaboration, Moore and Perry are working on a spoken-word album that they hope to release this fall in conjunction with Moore’s upcoming solo exhibition, “A New Republic,” on view from Oct. 2 to Nov. 27 at the Arthur Roger Gallery in New Orleans. Their producer is Waajeed, DJ for the hip hop group Slum Village.

The album includes lyrics by Perry centering on the Magnolia Projects in New Orleans — home to many New Orleans’ hip hop artists — as well a monologue by Moore that he describes as “very granddad Detroit,” where he is from. Perry said the lyrics articulate what happens at the intersections of history — in this case, the confrontation with the Confederacy that continues to this day.

“We have never stopped as a nation fighting the Civil War,” Perry said. “My colleague Eddie Glaude Jr. [the James S. McDonnell Distinguished University Professor and professor of African American studies] refers to it as a cold Civil War. It has moments of being hot. In recent history, it has been hot again. It has race at the center of it, but it’s also about these ideas about who belongs and who doesn’t. It’s about Black people, but also broadly about who is considered a legitimate part of the nation — who is here to be exploited versus who is here to fulfill the American dream.”

Moore created the cover art for the album, which will also appear as a 9-foot canvas banner at his exhibition. His hard line drawings echo the visual language of 19th-century posters and periodicals, with Harriet Tubman standing atop a pedestal as the central figure. He intentionally depicted Tubman not in her role as an abolitionist and conductor along the Underground Railroad, but rather, as a soldier and spy for the Union Army — the first woman to lead a military operation in the United States.

Portions of Moore’s illustration hearken back to slave life on Southern plantations and reference the Bronx projects where hip hop was born. He also incorporated Perry’s image and lyrics into his work (naturally, in hip hop style, with a shoutout to himself and Waajeed).

Miles Wilson, a rising senior and concentrator in art and archaeology, said he took the course largely due to his admiration for Moore and Perry.

“I thought it was amazing they were collaborating on a piece,” Wilson said. “I’ve seen Mario’s work. He’s such an amazing artist. And I’ve always loved jazz, blues, hip hop. So taking those things I love and contextualizing them with my own personal history, having an opportunity to do that is just amazing.”

Reckon, reimagine, create: Final projects use sound and video to ‘visualize the battle cry’

The students’ final projects took many forms based on their skill and comfort level working in various media, as well as their synthesis of the course materials.

Tachibe paired with David Song, an engineering concentrator who graduated in May, to create an animation that transports the viewer through the architecture of spatial violence Black Americans have experienced from the Reconstruction era to the present. Another student designed a modern battle uniform. Another created a video reassembling fragments of a photo of a Black drummer boy set against a sample of Otis Redding’s “Try a Little Tenderness.”

“They were all wonderful,” Perry said, “but also, really, really thoughtful. It wasn’t just ‘I’m going to dazzle you with this sound or image,’ they all had a lot of meaning behind them.”

Moore showed mutual admiration for Wilson, who is a talented visual artist, but chose to use only sound for his project, asking listeners to close their eyes and imagine they were transported to 1863. “It was nice, because you really had to go inside your mind,” Moore said. “You were forced into a state of mind to consider the sound and what it meant to you.”

Morgan Smith, a SPIA concentrator who graduated in May with a certificate in African American studies, created a video inspired by the movie “Glory.” She cut a Kanye West track called “God Level” into a soundscape featuring drums, horns and ad libs from Kendrick Lamar's "The Jig is Up" and Westside Gunn's "Versace" to envision a regiment’s ascension into heaven and journey home to the afterlife.

Smith took the course, she said, because she loves hip hop. She also came to find it served as a sharp lens for understanding our nation’s roots.

“Hip hop couldn’t have been a better way to think about the battle cry of these soldiers,” Smith said. “Thinking about what is behind that cry — the insistence that they are men themselves, that they deserve their freedom, that they are going to fight for it, that they are going to fight for their families’ freedom.”

The students said they found, as Moore initially surmised, that there is a deep connection between the Black soldiers and hip hop that serves to focus the nation’s history and also offers lessons for today.

“When it comes to our understanding of what’s happening now, it’s imperative for all of us as citizens to look at the past,” Moore said. “We have yet to reckon with that past, so we’re still dealing with the same issues over and over again, and we’re wondering why these things are happening without looking at ourselves and asking these questions.”