From the April 28, 2008, Princeton Weekly Bulletin(Link is external)

There is a small hill in a remote part of Turkey that looms large in the mind of John Haldon(Link is external), a professor of history at Princeton. It likely is the ruin of an ancient fortress, but for Haldon the site is an inspiration to find new ways to unearth the history of a particular landscape.

A specialist in Byzantine history, Haldon is the director of an archaeological and historical survey project based around the modern village of Beyözü in the north-central Anatolian region of Turkey. The site, originally known as Euchaita, then Avkat in Ottoman times, is a prime example of a provincial setting in Asia Minor. By deploying innovative technologies and multidisciplinary insights, Haldon hopes his study will reveal the big picture of an area that has thus far been unexamined.

“Fifth- to 10th-century inland Asia Minor is extremely poorly researched, if at all,” said Haldon. “It was an important part of the East Roman empire and became one of the core parts of the Byzantine empire until the 11th century. Yet we had no landscape study or settlement study, or anything, really.”

Haldon expects that the survey will answer key questions about the effects of human activity on the landscape, spanning 1,500 years. The project will explore where people settled and were buried, the impact of warfare, and how agriculture and pastoral farming affected the land and regional demographics.

Two and a half years ago, the Avkat Project emerged from Haldon’s work with the international Medieval Logistics Project, of which he is co-director. Based at the University of Birmingham in England, researchers involved in the logistics project are developing geographical information systems (GIS) and a relational database to examine land use and structures of resource allocation over several millennia across the European and Islamic worlds.

The findings at Avkat will add to the data from other ancient sites, particularly in Italy and Britain, and broaden historians’ understanding of Roman and Byzantine history.

“The idea is to cover as big an area as we can, using all kinds of technology, to get an accurate picture of the evolution of the landscape,” said Haldon. “That will then help us to understand the rest of the Middle East because we will be able to apply our model to other areas.”

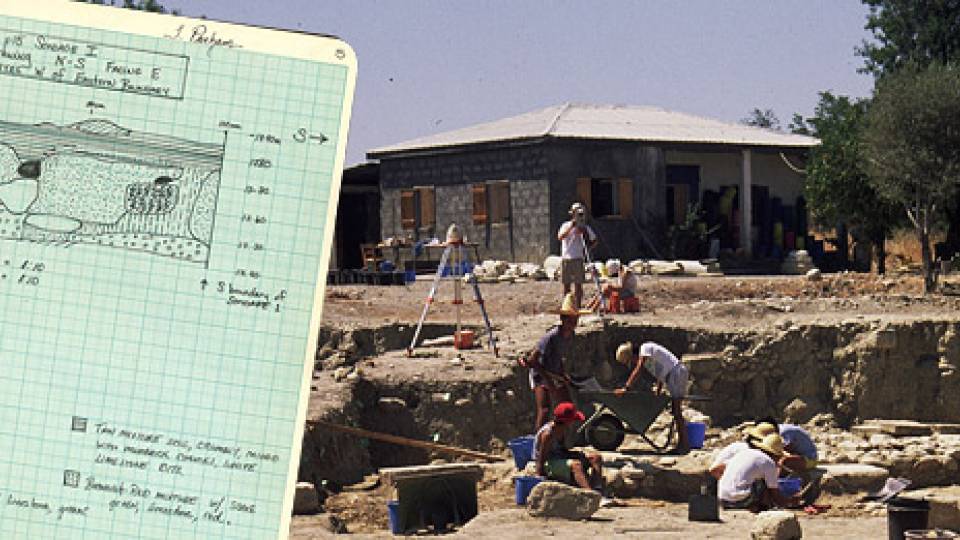

The field work at Avkat started last summer with an international team formed by Haldon. This summer, the team, which includes Princeton students, will return to Turkey to continue the work. If funding allows, Haldon estimates that the project will take up to 10 years to complete.

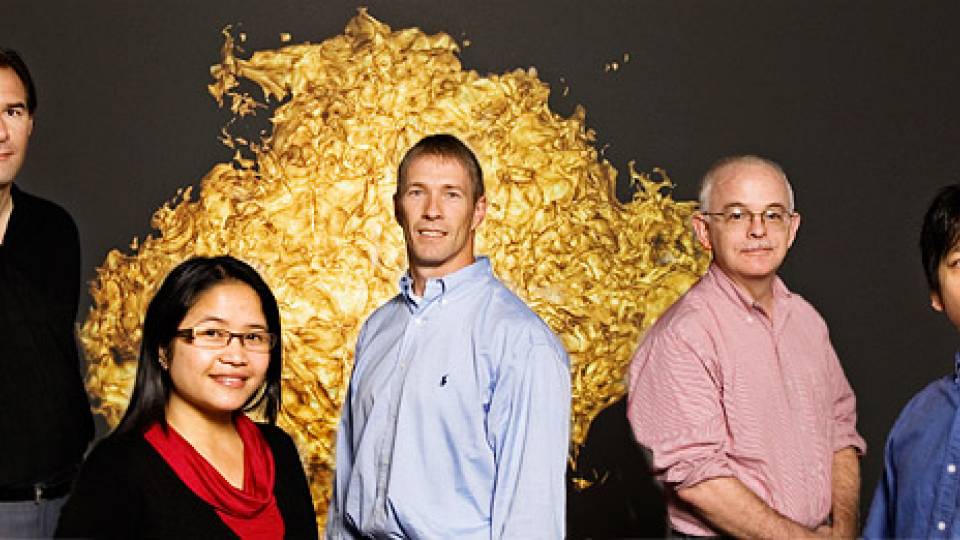

In summer 2007, members of the Avkat Project geophysics survey team prepared to set up a ground-penetrating radar unit and gridlines. From left: Meg Watters, director of the geophysics team from the University of Birmingham; Jonathan Winnerman, a member of Princeton’s class of 2008; Candace Weddle, a graduate student at the University of Southern California; Zachary Chitwood, Nebojša Stankovi´c and Jack Tannous, Princeton graduate students; and Christopher Goodmaster, a graduate student at the University of Arkansas. (Photo: Courtesy of the Avkat Project)

A multitalented team

The Avkat Project is a significant new development for Haldon, who until last summer had never before conducted archaeological field work. “It was a complete shift in my own research direction,” he said. “I could suddenly become a different type of scholar and get a different sort of team together to do field work.”

The author or co-author of more than a dozen books on Byzantine history, Haldon joined the Princeton faculty in 2005. He previously had taught at the University of Birmingham for 24 years, where he earned both his bachelor’s and doctoral degrees. He also has held visiting faculty positions at universities in France, Germany and the Netherlands.

Coming to Princeton has allowed Haldon to bring new resources to bear on the Avkat Project. Haldon has received support from numerous University departments and programs representing a range of disciplines, and he continues to seek additional funding opportunities on and off campus to sustain the project.

Haldon has formed a core research team that includes Hugh Elton, an associate professor of ancient history and classics at Trent University in Ontario, as well as James Newhard, an assistant professor of classics at the College of Charleston. Both Elton and Newhard are experienced field archaeologists.

This summer, 45 people will be part of the team at Avkat, including three Princeton graduate students and one undergraduate. Student volunteers from other universities in the United States will join the group as well, which will work at the site for four weeks. All told, the team will include historians, archaeologists, ethnographers, specialists in ceramics and numismatics, and technical experts in databases and geophysical tools.

As the leader of the project, Haldon has organized the participants into teams that will focus on specific tasks. Three teams will do “intensive field walking” and, led by Newhard, collect and record pieces of ceramics and other artifacts found in the area. Haldon will be part of a “roaming team” that will travel by trucks in large circles to plot other sites of importance in the region. Their work will be further informed by the findings of a Turkish team that will be conducting a field survey on a nearby hill, where Bronze Age artifacts recently were found. Also, in the village itself, Lale Özgenel, an assistant professor of architecture from Middle East Technical University in Ankara, Turkey, will lead a team of students who will conduct interviews with villagers to learn more about the community and its known history. Steve Wilkes, a remote-sensing project manager from the University of Birmingham, will lead the technical team.

“Professor Haldon’s enthusiasm is infectious,” said Zachary Chitwood, a doctoral candidate in history advised by Haldon who will be at Avkat this summer for the second time. “He takes a serious interest not only in his main area of study but in many other periods and areas of history as well. Overall, this is a wonderful project and I am proud to be a part of it.”

A Quickbird satellite image taken in July 2007 shows the village of Beyözü and its surrounding landscape, the focus of study in the Avkat Project. (Photo: Courtesy of the Avkat Project)

A high-tech approach

In order to glean the most from the field work, Haldon and his team are breaking new ground in their use of technology that is providing them with a digital framework.

By using computer mapping and modeling tools along with remote-sensing techniques such as ground-penetrating radar and satellite imagery, the researchers are able to collect extensive data in real time as well as to home in on certain kinds of information. This information then can be integrated with other datasets so that it is readily searchable.

“The best way to locate features and get a larger context is by using geophysical techniques, such as ground-penetrating radar coupled with magnetometry,” said Haldon.

“Then we can use satellite imagery to build a digital model and relate that to the surface evidence for ceramics and other small finds like coins. The GIS then links to a relational database, with software that enables us to organize spatial information visually,” he said.

“Much of what used to be done in the off season, such as data entry, photo management and find plotting, is now done in the field,” said Elton. “This is critical since almost all the collected data is digital.”

For senior Jonathan Winnerman, an art and archaeology major who went to Avkat last summer, a particular highlight was combining the field walking with the use of new technology.

Looking over the village of Beyözü (also known in different periods as Euchaita and Avkat) during the first field study of the Avkat Project last summer, Steve Wilkes, a remote-sensing specialist from the University of Birmingham, used an electronic distance measurer to help plot the bearings from satellite images to fixed points on the ground. (Photo: Courtesy of the Avkat Project)

“It was really amazing to see that dragging a box along the ground all day was actually able to generate the plan of the Byzantine fortress, several meters under the ground,” Winnerman said, referring to the 3-D computer model created of the ruined fortress using ground-penetrating radar equipment to suggest where the walls might have stood.

Another significant benefit of using technology for field surveys is that it is largely non-invasive to the land and local community. Later, when there are specific sites to explore, the team expects to do some excavating, but digging is not the primary approach. Also, since much of the work in Avkat is occurring outside of the village, disruption is not a major concern for this particular project, but there are locations within the village that are of interest to the scholars.

Tuna Artun, a doctoral candidate in history at Princeton who is Turkish and who was at Avkat last summer, said he spent a large amount of time with the local residents. “The villagers were truly hospitable, but also understandably curious about our presence,” he said. “I spent the majority of my time in the village proper, where numerous archaeological elements still exist — some of these were revealed by friends we had made in the village.”

Haldon is working to ensure that the technologies deployed at Avkat can be bundled into a toolkit for other archaeologists and historians to apply to their own field surveys.

“Our goal is to find ways of bringing all the different types of technology together in a single, integrated package in a way that will help us ask and answer all the questions we have ... and that we can make available to other scholars so they don’t need to do all the work we are trying to do,” said Haldon.

A product of this effort will be a website, currently being developed, that offers various levels of data about the Avkat Project, with restricted access to some of the research tools intended for specialists.

Mark de Groh, a doctoral candidate in history whose research focuses on the Ottoman Balkans and the Adriatic Sea from the 16th to 18th centuries, is going to Avkat this summer and already is imagining the ways such a toolkit might help scholars.

“The new approaches being developed at Avkat will allow us to unlock countless lost chapters of the past and will also help us to craft more informed histories than anything we could have hoped for, even 10 years ago,” said de Groh. “The project will push us to reconsider the nature of historical research on a fundamental level, and I am excited about working with a group of scholars ready to take on this challenge.”

As Haldon looks toward the future of the Avkat Project, he is very aware that funding is crucial. Thus far the project has received support at Princeton from the departments of history, art and archaeology and Near Eastern studies, as well as the Hellenic studies program and the Dean of Research Fund. Recently, Haldon has applied for grants from the National Endowment for the Humanities and the National Science Foundation, emphasizing the interdisciplinary nature of the project and its focus on developing an ongoing educational and research tool for scholars.

“What I’ve done is to bring different specializations together and to globalize resources and agree on a common project that everyone can get something out of in terms of their own personal research, but which contributes both to their own fields and each others’,” said Haldon. “There is a perfect combination of skills and technologies in what is a win-win situation.”

Earlier this spring, Haldon gave a Lunch ’n Learn talk on the Avkat Project, sponsored by the Office of Information Technology, which can be downloaded as a podcast(Link is external).