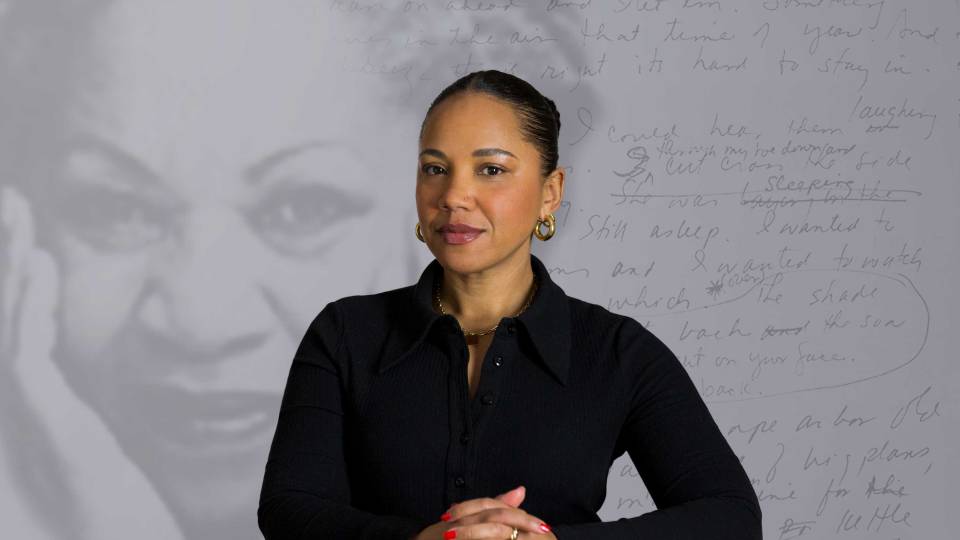

The Princeton and Slavery Symposium, held Nov. 16-19 at Princeton University, marked the public launch of the Princeton and Slavery website, and featured panels, performances, guided tours and arts events. Following her keynote address, Nobel laureate Toni Morrison, the Robert F. Goheen Professor in the Humanities, Emeritus (left), addresses audience questions during a conversation with Tracy K. Smith, the Roger S. Berlind ’52 Professor in the Humanities and a professor of creative writing in the Lewis Center for the Arts, and the U.S. Poet Laureate.

The Princeton and Slavery Symposium, held Nov. 16-19 at Princeton University, featured panels, performances, guided tours, exhibitions, film screenings and a keynote speech by Nobel laureate Toni Morrison. Hundreds of people attended the events: Princeton students, faculty and staff members; scholars and higher education administrators from across the country; and community members. Thousands watched the proceedings through livestreaming.

“The Princeton and Slavery Project(Link is external) is a scholarly investigation of the University’s historical involvement with the institution of slavery,” Martha Sandweiss(Link is external), professor of history(Link is external), and the founder and director of the Princeton and Slavery Project, told the packed audience Friday afternoon in Richardson Auditorium, who had come to hear Morrison, Princeton’s Robert F. Goheen Professor in the Humanities, Emeritus.

“It has its roots in a small undergraduate seminar I taught almost five years ago and has grown to include dozens of team members, some 40 colleagues, mostly undergraduate and graduate students here at Princeton,” Sandweiss said. She noted that the Princeton and Slavery website has the equivalent of more than 800 printed pages, as well as some 370 primary source documents, including videos, graphs, interactive maps, lesson plans and more.

“At the symposium, we will explore the ways in which Princeton University is the history of the United States of America writ small, a place where liberty and slavery were intertwined from the start,” Sandweiss said.

She noted that Morrison, “perhaps more than any living writer, has challenged us to imagine the experience of slavery itself and grapple with its lingering impact on American lives.”

Martha Sandweiss, professor of history, and the founder and director of the Princeton and Slavery Project, introduces a series of panels on Saturday, noting that online visitors from 95 countries viewed the Princeton and Slavery website since its launch a week ago.

Tracy K. Smith(Link is external), the Roger S. Berlind ’52 Professor in the Humanities and a professor of creative writing(Link is external) in the Lewis Center for the Arts(Link is external), and the U.S. Poet Laureate, introduced Morrison.

Smith said: “What would the world know about slavery’s deep and ongoing psychic toll upon the slave, the slaveholder and each of the lives they have given birth to, were it not for Morrison’s contribution of masterwork after masterwork to the literary canon?”

As Morrison came on stage, a wide smile lighting up her face, she raised her arms in welcome. The audience leapt to its feet in one of several standing ovations that punctuated the event.

“Oh my, this is nice!” Morrison said. “Thank you for the praise. I am not humbled,” Morrison said, eliciting warm laughter from the audience. They applauded loudly when Morrison admitted: “I came here because they’re going to rename a building with my name,” referring to the renaming of West College to Morrison Hall. “That sounds good, doesn’t it?”

Describing her exploration of the Princeton and Slavery website, Morrison said: “The focusing of our students and faculty on the history of Princeton and slavery makes for very powerful and fruitful research. ... This kind of academic research strengthens us all.”

Morrison, whose novels “Beloved” and “A Mercy” focus on slavery, talked about her own family’s connection to slavery. One of her grandfathers, who was 3 years old in 1865 at the end of the Civil War, became alarmed whenever he heard the word “emancipation” whispered by the adults around him. “When it finally came, he hid under the bed he was so frightened, and refused to come out until his mother convinced him that emancipation meant freedom, not death,” Morrison said.

During a conversation with Smith, Morrison emphasized the importance of the arts in academic inquiry.

Morrison, who taught courses at Princeton in the humanities and African American studies(Link is external), then creative writing, credited Ruth Simmons, Princeton’s former vice provost who brought Morrison to Princeton in 1989, for helping her procure the funding for the Princeton Atelier(Link is external), an academic program Morrison started. The Atelier, whose first guest artist was the cellist Yo-Yo Ma, brings together professional artists from different disciplines to create new work in the context of a semester-long course. (Simmons spoke on a Saturday panel at the symposium.)

Smith opened up the conversation with questions from the audience, which had been submitted on index cards, as well as via social media. Questions ranged from “What is the significance of storytelling in our current political context?” to “What was your own first memory of race?”

Noting that storytelling is “the way human beings exist,” Morrison, who has her own Twitter account, nevertheless lamented the acronyms and abbreviations of social media. “We’re losing language, nobody’s expanding it, it’s shrinking into little spaces where you can put two or three letters. That is so problematic to me because there is so much to say, still.”

Morrison described her hometown of Lorain, Ohio, in the 1930s, as a mixed neighborhood where “everybody was dirt poor, that was what we had in common,” and where “we gardened because we ate it, not because it was a cute little thing to do.” While her older sister remembered racial slurs by some neighbors, Morrison said she did not. Rather, she first learned about race when she went to the historically black college Howard University in Washington, D.C.

“All of a sudden, the buses have labels on who sat where, and there were fountains that said ‘colored’ and ‘white.’ And I thought that was a hoot because who would spend money on doing that twice? How wasteful,” Morrison said.

Marcelo Norsworthy, a graduate student in the Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs(Link is external), came to the event “to hear Morrison’s views on how we can learn from history. Her creativity, dedication and compassion were inspirational,” he said. The recollections from Morrison’s youth were a highlight for him, to learn “how the intersection of race and class played out as a child in that era.”

First-year student Anglory Espinal of New York City said she attended “because I was intrigued that Princeton was recognizing their involvement with slavery as well as recognizing someone who vividly and beautifully translated the stories of slavery into words. It was truly an amazing experience.”

Espinal’s favorite moment was when someone asked what students should be doing to move forward with these issues beyond the symposium weekend, and Morrison replied: “I have no idea. You should ask yourself. You have a brain and blood in your veins.”

First-year student Cierra Moore of Trenton, New Jersey, said she came to see Morrison “impart real-time wisdom. I felt like I was sitting in quite a privileged seat, having my school’s ties to the slave trade, of which my not-so-distant ancestors were victims, explained to me by a Nobel laureate. And not only explained, but broken down in a colloquial and familiar way that I could digest easily.”

“We’re not the ultimate generation,” Morrison said in response to a question of how to take the findings of the slavery project beyond the weekend symposium. “We’re not gonna solve all these things. What we’re gonna do is push the inquiry forward, and then some of your great-grandchildren will take over and it will be better because they have known us and known what we thought, the mistakes we made and the solutions we were able to provide.”

Speakers from the panel “The Princeton and Slavery Project: Some of What We’ve Learned” take questions from the audience. From left: Daniel Linke, University archivist; Craig Hollander, assistant professor of history, The College of New Jersey; Lesa Redmond, a 2017 Princeton alumna; Joseph Yannielli, postdoctoral associate, Yale University; Trip Henningson, a 2016 Princeton alumnus; and Isabela Morales, a graduate student in the Department of History at Princeton.

What we’ve learned: Panels explore engagement with historical data, next steps

In a series of panels on Saturday, scholars, faculty and alumni discussed the findings of the Princeton and Slavery Project.

In her opening remarks, Sandweiss said she has been asked, “Why a website, why not a book?”

“A website can engage so many people,” she said. “Since last week, the website has been viewed by people in 95 countries. Since the launch, people have contributed primary source documents we missed. This is precisely what we hoped would happen.”

She touched on a few of the many stories the website explores, including the fact that the University’s first nine presidents owned slaves, as did all seven who signed the University charter. Sixteen of the founders inherited, traded or owned slaves, and many faculty members owned slaves.

“Wealth derived from slave labor helped fund the construction of Nassau Hall,” Sandweiss said, “but let me note: We found no evidence that the University as an institution owned slaves.”

The project’s findings also debunk two myths, she said. While the University’s 18th- and early-19th-century students “lived in a landscape of slavery, in which they could look out the back of Nassau Hall and see enslaved people tending to the cherry orchards and cattle of Prospect Farm,” Princeton’s Southern students — who at times comprised as much as 63 percent of the student body — did not bring their slaves to campus. Also, the town of Princeton did not have a community made up of African American descendants of the slaves those students supposedly left behind.

“With our stories now out on the table, we lay the groundwork for powerful conversations moving forward,” Sandweiss said.

Daniel Linke, the University archivist who has worked with Sandweiss since the project’s inception, introduced the panel “The Princeton and Slavery Project: Some of What We’ve Learned.” “Intellectual curiosity has sustained us from the start,” he said.

Plucking anecdotes from the findings, five scholars unpacked several of the stories behind the research. Below are two; more can be found on the website.

Lesa Redmond, a 2017 alumna, gave an overview of her senior thesis on John Knox Witherspoon. “Witherspoon’s life represents the contradiction between liberty and bondage,” Redmond said. Witherspoon, the former Princeton president and co-signer of the Declaration of Independence, engaged in educating free blacks even as he remained a slaveholder at his Princeton farm Tusculum.

Joseph Yannielli, a postdoctoral associate at the Gilder Lehrman Center at Yale University, demonstrated, via a heat map, the data on Princeton’s Southern student population, many of whom were sons of wealthy slave owners. “Slavery and racism became part of the DNA on campus,” said Yannielli, a former postdoctoral research associate with the Humanities Council(Link is external) and the Center for Digital Humanities(Link is external) at Princeton who served as the project manager and lead developer for the Princeton and Slavery website. He noted that more Princeton graduates fought for the Confederacy than the Union (although the Civil War veteran inscriptions in Nassau Hall do not note on which side each soldier fought).

Other speakers included Craig Hollander, an assistant professor of history at the College of New Jersey and a former postdoctoral researcher at Princeton; Trip Henningson, a 2016 Princeton alumnus; and Isabela Morales, a doctoral candidate in history at Princeton who has been involved in the Princeton and Slavery Project since 2013.

The panel “The Princeton and Slavery Project: How It Shapes Our Broader Understanding of Universities and Slavery” featured Leslie Harris, a professor of history at Northwestern University, and Ruth Simmons, president of Prairie View A&M University.

“Princeton has definitely set a new standard for us all,” said Harris, who spearheaded a similar project at Emory University in 2004.

Wallace Best, a professor of religion and African American studies at Princeton (center) moderates the panel “The Princeton and Slavery Project: How It Shapes Our Broader Understanding of Universities and Slavery” with Leslie Harris, a professor of history at Northwestern University (left), and Ruth Simmons, president of Prairie View A&M University.

After giving an overview of the range of universities — from Harvard to Clemson — that have undertaken scholarly research to examine their connections to slavery, Harris asked: “How does that inform what we do today?” She said she hopes that everyone involved in such undertakings — faculty, students and staff — can “become change agents,” and noted the Princeton and Slavery website has “created the possibility of a living history.”

In 2007, during her previous tenure as president of Brown University, Simmons initiated the first exploration by an Ivy League university into its history as it relates to slavery — the Steering Committee on Slavery and Injustice. Simmons, the first African American president of an Ivy League university, previously was president of Smith College and before that served in several administrative roles at Princeton. She also has served as a Princeton trustee.

“If there is one practice that universities in particular should endorse, it is that of uncovering facts and revealing truths,” she said. “... A commitment to a robust transparency will ultimately lead to disclosures of the type we have been privileged to read and the rich material assembled in conjunction with the Princeton and Slavery Project.”

During the Q&A, moderator Wallace Best(Link is external), a professor of religion(Link is external) and African American studies at Princeton, asked the panelists what this process taught them about universities.

Simmons said that at Brown, a portrait of that university’s first president, a slave owner, was on the wall of her office, so she saw it every day. People often asked her how she felt about that. She said she always responded: “I feel quite fine about it because, after all, I’m here now.

“Evidence of change is an amazing way to heal the pain of past transgressions,” she said.

“[Emory] may be historically white but it’s currently diverse,” Harris said. “... And you have that here at Princeton. There was not a day that I worked on the Emory project that I did not feel hopeful.”

Princeton President Christopher L. Eisgruber commended Sandweiss for her leadership and vision as he opened the final panel of the day, “The Princeton and Slavery Project: How It Changes Our Understanding of American History and Poses a Challenge to Historical Commemoration.”

“This remarkable weekend of scholarly discourse and intellectual engagement represents the best way for universities to engage with their past, through rigorous, thoughtful, truth-seeking research that simultaneously educates students, enhances knowledge and contributes to debates both on this campus and beyond it,” Eisgruber said.

Princeton President Christopher L. Eisgruber (left) leads the Q&A following the panel “The Princeton and Slavery Project: How It Changes Our Understanding of American History and Poses a Challenge to Historical Commemoration,” with Danielle Allen, the James Bryant Conant University Professor at Harvard University (center), and Eric Foner, the DeWitt Clinton Professor of History at Columbia University (right).

Joining Eisgruber on the stage were Danielle Allen, the James Bryant Conant University Professor at Harvard University and director of Harvard’s Edmond J. Safra Center for Ethics, and Eric Foner, the DeWitt Clinton Professor of History at Columbia University, who authored a report on that institution’s examination of its ties to slavery.

Foner said the Columbia and Princeton investigations into their pasts are “part of a long overdue reappraisal of American history that’s become more and more necessary in the past few years. However Princeton decides to commemorate this newly discovered part of its history, it’s doing a national service.”

Allen, a 1993 Princeton alumna and former trustee whose book “Our Declaration” Eisgruber chose for the 2016 “Pre-read,” said the slavery project gave her new insights into how the public should learn and remember the findings of scholars researching American history. She said Princeton, Harvard, Columbia and Brown are on a short list of “perpetual institutions” that predate the founding of the United States and “intend to be here forever.”

“Every one of these institutions is a living museum,” Allen said, comparing them to the Mall in Washington, D.C. “If people come to visit us, they are learning the whole history of this country. So how do we actually apply the correct historical standards to our jobs as inhabitants of a living museum? I think the work that Professor Sandweiss and her colleagues have done shows us what the standard is.”

Allen’s remarks about universities as living museums resonated with senior Meagan Raker. “I thought this was a beautiful point, which highlighted our opportunity to tell a more complete story of Princeton’s past and the need to carry that story on into the future,” said Raker, a history major.

She was among the students in Sandweiss’ fall course “Princeton and Slavery” who devised and led historical walking tours during the symposium on Sunday afternoon. Raker said on the first day of class she learned about the slave sale in front of Maclean House in 1766 that artist Titus Kaphar commemorates with an installation on view on the lawn of Maclean House, commissioned by the Princeton University Art Museum(Link is external). On Thursday, Raker attended a talk(Link is external) Kaphar gave about his work. “As I described that event and Titus’ work to my tour group, I was so proud to be incorporating research, public history and art in order to promote such an important dialogue on this campus,” she said.

Undergraduates lead conference participants on historical walking tours and personal history tours as part of the symposium program.

Other conference highlights, many related to the arts, included:

- Historical walking tours led by students in Sandweiss’ fall course “Princeton and Slavery,” and personal walking tours led by students in the course “Autobiographical Storytelling: Princeton, Slavery and Me,” taught by Brian Herrera(Link is external), assistant professor of theater(Link is external) in the Lewis Center for the Arts.

- Readings of short plays based on historical documents drawn from the archives of the slavery project, commissioned by and performed at McCarter Theatre Center(Link is external).

- Screenings of the video “Facing Slavery: Princeton Family Stories” by Melvin McCray, a 1974 Princeton alumnus, at Princeton Garden Theatre(Link is external).

- “Impressions of Liberty(Link is external),” an art installation by Titus Kaphar, commissioned by the Princeton University Art Museum, which focuses on the auction of slaves owned by Princeton’s first president, Reverend Samuel Finley.

- “Making History Visible: Of American Myths and National Heroes(Link is external),” an exhibition on view through Jan. 14, 2018, at the museum, which brings together 18th- and 19th-century as well as modern and contemporary works — including works by Kaphar — to consider the ways in which artists have depicted American history, including the institution of slavery.

View social media engagement about the conference in a Storify recap(Link is external).

Actors Nicole Ari Parker (seated left), Wayne Pretlow, Esau Pritchett and Robert David Grant participate in a staged reading of “Elizabeth” by Dipika Guha, one of seven new short plays based on historical documents drawn from the archives of the Princeton and Slavery Project, which were commissioned by and performed at McCarter Theatre Center as part of the symposium programming.

Dan Day contributed to this story.