As rain darkened the red earth atop Bolivia’s largest silver mine, Peter Schmidt watched children only a few years younger than him emerge from the honeycomb of hand-excavated tunnels to dump minecarts of ore before hurrying back inside the mountain’s labyrinth of compact tunnels.

Schmidt — a high school graduate from St. Louis studying in Bolivia through Princeton’s Novogratz Bridge Year Program — was struck by watching members of his own generation mine the Cerro Rico, or “rich mountain,” in much the same way as when the Spanish first penetrated the Andean mountain in the 16th century.

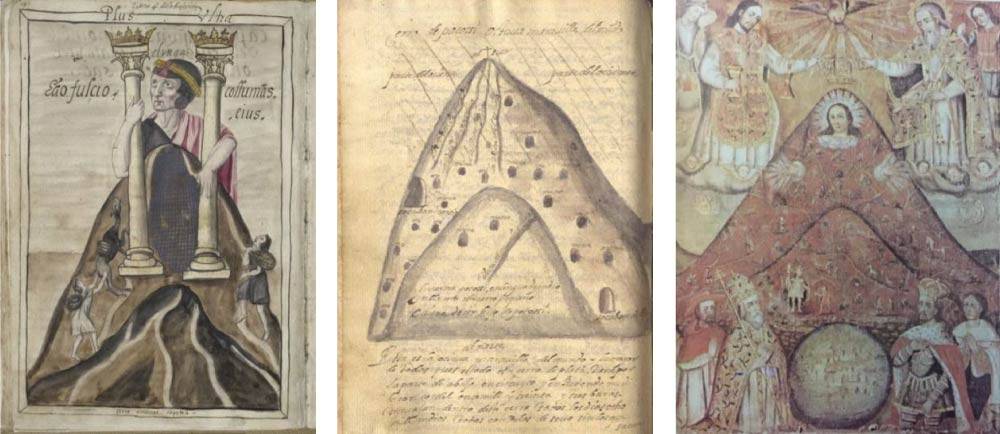

For his senior thesis, Peter Schmidt, Class of 2020, wrote a novel that uses the violent history of Bolivia’s Cerro Rico — which has been mined for silver since the 1500s — to examine recent efforts worldwide to grant natural features legal personhood. A source of wealth for the Spanish Empire, the Cerro Rico was depicted as the foundation of Holy Roman Emperor Charles V’s coat of arms in 1590 (left). A map from around 1600 (center) shows the mine entrances and principal veins of what was called the “eighth wonder of the world.” A painting from circa 1720 portrays the Cerro Rico as the Virgin Mary.

“This place had a very strong and strange effect on me and I knew I wanted to write a book about it someday,” Schmidt said. Four years later, he has written a novel as his Princeton senior thesis that provides the mountain that spoke to him that day with its own voice, one that pleads for justice after nearly 500 years of being stripped, exploited and hollowed out.

His novel, “A Mountain There,” uses the violent history of the Cerro Rico to examine increasing efforts worldwide to grant natural features such as rivers, lakes and forests — and in some cases nature itself — the rights and protections of legal personhood. Schmidt documents a fictional push to achieve personhood for the Cerro Rico through court filings, news articles and correspondences that he created based on his research at Princeton, as well as on fieldwork in Bolivia supported by senior thesis funding from the Princeton Environmental Institute (PEI).

“With our litany of environmental disasters, and climate change, the idea of treating environmental features as legal persons is becoming more and more urgent,” said Schmidt, who graduated from Princeton on June 2 with a bachelor’s degree in Spanish and Portuguese and a certificate in environmental studies. He received the Environmental Studies Book Prize in Environmental Humanities for his thesis during the Program in Environmental Studies Class Day ceremony May 29.

“This book asks how the world would look if a mountain could speak and if a mountain could be granted the opportunity to testify in open court,” Schmidt said. “Fiction creates a space where you can ask those kinds of questions and treat them seriously.”

Schmidt’s novel builds on recent actions that have provided nature with individual rights. In 2010, Bolivia passed the Law of the Rights of Mother Earth that provides the natural environment with certain protections for which individuals and groups can be punished for violating. In New Zealand, the area known as Te Urewera and the Whanganui River respectively became the first (in 2014) and second (in 2017) natural resources in the world to be given a legal identity that includes self-ownership. Similar proposals have been presented — and largely defeated — for natural features such as Lake Erie in the United States.

In his novel, Schmidt (pictured) documents the efforts of his main character, an American lawyer, to have the Cerro Rico granted legal personhood. The novel is presented as a collection of filings, articles and correspondence that Schmidt created based on his research at Princeton, as well as on fieldwork in Bolivia supported by PEI. The Cerro Rico is a character that can speak, following the traditions of Indigenous Andean cultures and Latin American writers such as Jorge Luis Borges.

In Schmidt’s novel, the main character, Clancy, is an American lawyer for the International Court for Planetary Justice. He is researching the history of the Cerro Rico for a petition that it be granted personhood. His pursuit leads him into a correspondence with Carmen Condori, who grew up in the nearby city of Potosí and who he believes possesses a rare book — written by a fictional author Schmidt created named Lucinda Mamani — that he needs.

Clancy — who is based on Schmidt — is ultimately drawn by the tragic story of the Cerro Rico to visit and commune with the mountain. He writes in a letter to Carmen, “It would be disrespectful of me to suggest that I can even comprehend the violence that this place contains. So many lives have disappeared here, and so many stories have been lost. If the mountain could speak again, it would need a million years to tell them all.”

“The whole story was partly motivated by the strange fact that I — a random kid from a Missouri suburb — suddenly has this very strong relationship with a part of the world that he didn’t even know existed a few years ago,” Schmidt said. “This project is an ode to the last five years of my life, which, thanks to Princeton, have been wrapped up in Bolivia of all places.”

Schmidt also chose the Cerro Rico because of its outsized role in bankrolling the expansion of European colonialism across Latin America and the world, he said. The mines of the Cerro Rico once provided an estimated 80% of the world’s silver during the Spanish colonial period. Potosí was among the largest cities in the Americas. Since the 16th century, up to 8 million miners are thought to have lost their lives in the Cerro Rico’s mines, which are still active. Deforestation and erosion from centuries of mining for silver and other valuable metals have ravaged the local environment, while thousands of haphazardly dug mineshafts have rendered the mountain dangerously unstable.

“It seems to me that the mountain had an active role in creating the world we live in today,” Schmidt said. “The fact that the mountain itself is collapsing and, in a sense, the world we live in today — this super globalized interconnected world — also is collapsing, that felt like a metaphor that was too elegant to pass up.”

Schmidt explores through Clancy’s research the roots of international law, individual rights and sovereignty. He focuses on the work of Francisco de Vitoria, the 16th-century Dominican theologian and jurist who argued for the rights of Indigenous peoples to have dominion over their land — at the same time that the Spanish were engaged in unmitigated slaughter and plunder.

Schmidt — who received a bachelor’s degree in Spanish and Portuguese and a certificate in environmental studies — first visited the Cerro Rico after high school and was captivated by the sight of children not much younger than him working in the mines and mine entrances (pictured) in much the same way as when the Spanish first penetrated the mountain.

In a court filing, Clancy equates environmental personhood with past struggles for equality: “Such an extension of rights is almost always inconceivable until it happens, at which point it becomes, with the clarity of hindsight, commonsense.”

“A Mountain There” debates what it means to be a person, particularly if that classification is given to an inert landform. “Personhood is double-edged,” Clancy writes to Carmen, asking if the mountain would become culpable for the millions of people that have died inside of it. Carmen replies more pointedly: “You act as if you’re doing the Cerro Rico a favor. If I were a mountain, I wouldn’t want to be on equal footing with humans — at least, not the ones I know.”

The correspondence between Clancy and Carmen illustrates the conflict that can arise between outside “saviors” and the people and places they want to “save.”

Clancy realizes that modern society wants to grant personhood to natural features when it was that society that silenced nature’s voice in the first place: “We at the Institute may congratulate ourselves for the provocative idea that mountains have personhood, but in fact the notion has been in practice for hundreds of years.”

At one point, Carmen sends Clancy a passage — written by Schmidt — from Mamani’s book: “Do not make the mistake of thinking that the mountain cannot speak. It speaks. It is speaking. The question at hand is not whether we are capable of understanding what it has to say — we are, and have always been — but whether we care to try.”

Carmen is initially dismissive and hostile toward Clancy — who is seeking justice for a Bolivian mountain from his office in Connecticut — telling him: “You would do well to find a nice shady valley to sit in, make some money, and take care of your dear grandparents instead of worrying about a mountain in a country you know nothing about.” At the same time, she debates with the Cerro Rico, the voice of which she can hear, on whether to help Clancy by providing him with the book and the personal insight into the Cerro Rico he’s seeking for his work.

“Peter’s thesis shines for both its deep intellectual engagement and scholarly rigor, its confidence to ask questions that may not have answers, and, of course, its creative ambition,” said Nicole Legnani, assistant professor of Spanish and Portuguese and Schmidt’s senior thesis co-adviser. “If we consider that Peter’s first encounter with Bolivia was due to his bridge year in Bolivia, his thesis is thoroughly ‘Princetonian’ even as it is deeply committed to communities and experiences far beyond campus.”

Schmidt’s presentation of the Cerro Rico as a character is rooted in the Indigenous animist traditions of the Andes, Legnani said. At the same time, he constructs a version of our modern world in which mountains talk and people represent them in court, which follows the tradition of Latin American writers such as Jorge Luis Borges: “Not only are the limits of the human and the person challenged by this novel, so too are constructions of time,” she said.

Schmidt’s co-adviser Daphne Kalotay, a lecturer in creative writing and the Lewis Center for the Arts, said that Clancy serves as the reader’s intellectual guide, providing background that he himself is learning and recording.

“I love that the very premise of the story is that a lawyer is making the case for the personhood of a despoiled mountain,” Kalotay said. “As this notion is developed, we readers confront the implications of environmental personhood while also becoming more aware of sociopolitical, geological and economic interrelationships.

“Fiction also allows readers to enter a topic not just intellectually but emotionally, viscerally,” she continued. “Peter created a protagonist in Carmen whose lifelong relationship to the mountain is primal.”

A tailings pond for a mineral processing plant at the foot of the Cerro Rico. After centuries of mining, deforestation and erosion have ravaged the local environment, while thousands of hand-excavated tunnels and mine entrances have rendered the mountain dangerously unstable. In his novel, Schmidt equates environmental personhood with past struggles for equality and explores what it could mean for a landform to be treated as a person.

Schmidt worked closely with Legnani and Kalotay over several months to construct a novel that would be meaningful and enjoyable, as well as experimental. “Peter’s great strength — besides his innate talent — is his willingness to go back to the drawing board as many times as needed in order to find his way into his material,” Kalotay said. “That ability to scrap early drafts is actually a skill, too.”

Writing a novel was a challenging transition for Schmidt after focusing on environmental research during his time at Princeton, he said. He wrote two junior papers, one that explored renewable energy and politics in Puerto Rico, and the other on the use of military technology in Brazil to locate mineral wealth in the Amazon by aircraft. In 2017, he studied the effect of the global popularity of quinoa on rural farmers in Bolivia.

After Princeton, Schmidt will work with two Brazil-based advocacy groups. He’ll help the nonprofit research institute Imazon (Amazon Institute of People and Environment) — which is dedicated to preventing deforestation in the Amazon — use storytelling and science communications to influence policymakers. Schmidt also will conduct research related to climate change and global security policy for Instituto Igarapé, which uses research, technology and policy to solve social issues related to security, justice and development. Stateside, Schmidt will also work full-time at the New York City-based immigration law firm Sethi and Mazaheri and its related nonprofit group, the Artistic Freedom Initiative, where he will help artists seeking asylum.

“One thing I learned is that the trajectory of a research project and the trajectory of a novel rarely converge,” Schmidt said. “With a novel, there’s a lot of thinking up front, but you have to go pretty immediately to an empty page and start putting things out and seeing how they fit together.

“I would get to a point in the creative aspect and realize I needed to do a lot of research in order to proceed,” Schmidt said. “The academic questions were guided by the story, and the story was guided by the academic questions.”