A new modeling approach can help researchers, policymakers and the public better understand how policy decisions will influence human migration as sea levels rise around the globe, a paper published Nov. 26 in Nature Climate Change suggests.

In the paper, a group of internationally known climate change researchers suggest that global policy decisions about greenhouse gas emissions and policy decisions about where people live and work in coastal areas will determine whether people need to migrate and where they may go.

Such modeling can help to determine which economic policies, planning decisions, infrastructure investments, and adaptation measures influence how, why, and if people migrate to new places as a result of sea level changes. This will help policymakers better anticipate the effects of realistic policy alternatives.

“We’ve been looking at this problem the wrong way. We’ve been asking how many people will be vulnerable to sea level rise and assuming the same number of people will migrate,” David Wrathall, the paper’s lead author and an assistant professor in Oregon State University’s College of Earth, Ocean, and Atmospheric Sciences. “In reality, policies being made today and moving forward will exert a strong influence in shaping migration. People will move in very specific ways because of these policies.”

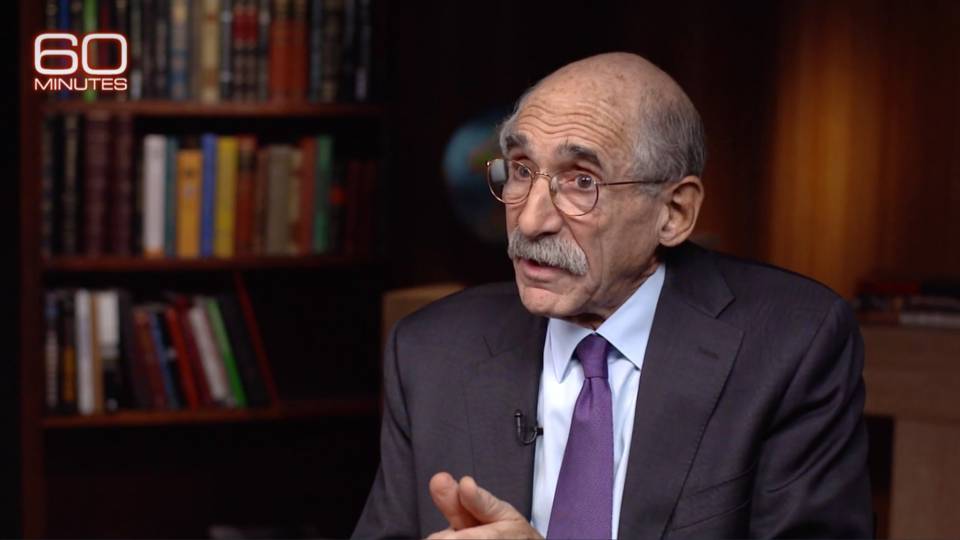

“Migration policy should have the objective of improving outcomes for potential migrants, for those already living at migrants’ target destinations, and for those left behind who might want to migrate but lack the necessary resources,” said paper co-author Michael Oppenheimer, the Albert G. Milbank Professor of Geosciences and International Affairs and the Princeton Environmental Institute. “New techniques and a variety of models, combined with data on migration, hold the promise of providing a rational basis for migration policy,” said Oppenheimer, who also directs the Center for Policy Research on Energy and the Environment.

Minimizing the negative impacts of sea level rise presents a significant societal challenge. About a billion people around the world live near a coastline and could be impacted directly or indirectly by rising sea levels as the planet warms due to climate change.

Armoring coastlines against surging tides and rising waters could impact whether people are able to stay in their homes or need to relocate. Tax incentives and zoning regulations that allow businesses to locate near ports, a global trend, potentially puts whole industries and labor markets at risk. Even interest rates can affect who can afford to borrow money, which could be a crucial part of people’s decisions to migrate.

Furthermore, global decisions about the management of greenhouse gas emissions, which are responsible for the warming of the planet, could impact how quickly the planet warms and sea levels rise, the researchers noted.

“Right now, people are actually moving toward coastlines that will be more and more vulnerable as the planet warms,” Wrathall said. “The only thing that will change this trend is policy. If we start changing the incentives to live, work and invest in safer places, we could make sea level rise-induced migration less expensive and disruptive down the line.”

The researchers suggest that computational models should focus on global emissions policies under discussion to quantify migration impacts of sea level rise scenarios.

“All greenhouse gas emissions scenarios have a similar effect on sea level rise until about the year 2050,” Wrathall said, “but then sea level rise outcomes really start to diverge. So a first step is modeling sea level rise, policy and migration in the near term.”

Researchers should then simulate migration outcomes for future adaptation policies, which include defending coastlines and retreating away from them, noted Wrathall. Policy decisions also need to be modeled for their impact on the communities or regions where migrants are relocating, since those arriving will have a significant impact on their new community as well. Perhaps most importantly, policymakers seeking to understand how their decisions may affect how people move due to sea level rise cannot afford to experiment on vulnerable populations with expensive and potentially dangerous.

“Future migrants will need jobs, houses and health care,” Wrathall said. “Their kids will need schools. The availability of these things will affect where migrants go and their quality of life when they get there.”

Co-authors of the paper include global experts on sea level rise and environmentally forced migration from the United States, United Kingdom, and Europe. The research was supported by the National Socio-Environmental Synthesis Center with funding from the National Science Foundation.

By Michelle Klampe, Oregon State University, with B. Rose Kelly, Woodrow Wilson School