Amazon fire

The Amazon is the world’s largest and most diverse tropical forest and the ancestral home of over 1 million indigenous peoples. How to preserve it was the centrally urgent theme at a conference at Princeton on Oct. 17-18.

The conference “Amazonian Leapfrogging: Long-term Vision for Safeguarding the Amazon for Brazil and the Planet” at Princeton Oct. 17-18 offered an opportunity to discuss an alternative vision for the Brazilian Amazon, which is threatened by illegal deforestation, fires and socioeconomic inequality. Shown from left: Beto Veríssimo, a Brazil LAB scholar and co-founder and senior researcher of the nonprofit Imazon; Ilona Szabó, director of the think-and-do-tank Igarapé; Michael Celia, the Theodora Shelton Pitney Professor of Environmental Studies and director of the Princeton Environmental Institute; and Tasso Azevedo, a Brazil LAB scholar and coordinator of MapBiomas, a land use mapping initiative.

“Safeguarding the Amazon and its rich bio-social diversity and environmental services for Brazil and the planet is a key mandate for our times,” said João Biehl, the Susan Dod Brown Professor of Anthropology and director of the Brazil LAB at the Princeton Institute for International and Regional Affairs (PIIRS), in his opening remarks. “It necessitates our very best ideas and practices.”

The conference, “Amazonian Leapfrogging: Long-term Vision for Safeguarding the Amazon for Brazil and the Planet,” offered a platform for Princeton scholars and Brazilian scientists, environmental and indigenous leaders, policy experts, artists, business innovators, and social entrepreneurs to discuss an alternative vision for the Brazilian Amazon, currently threatened by illegal deforestation, fires and socioeconomic inequality.

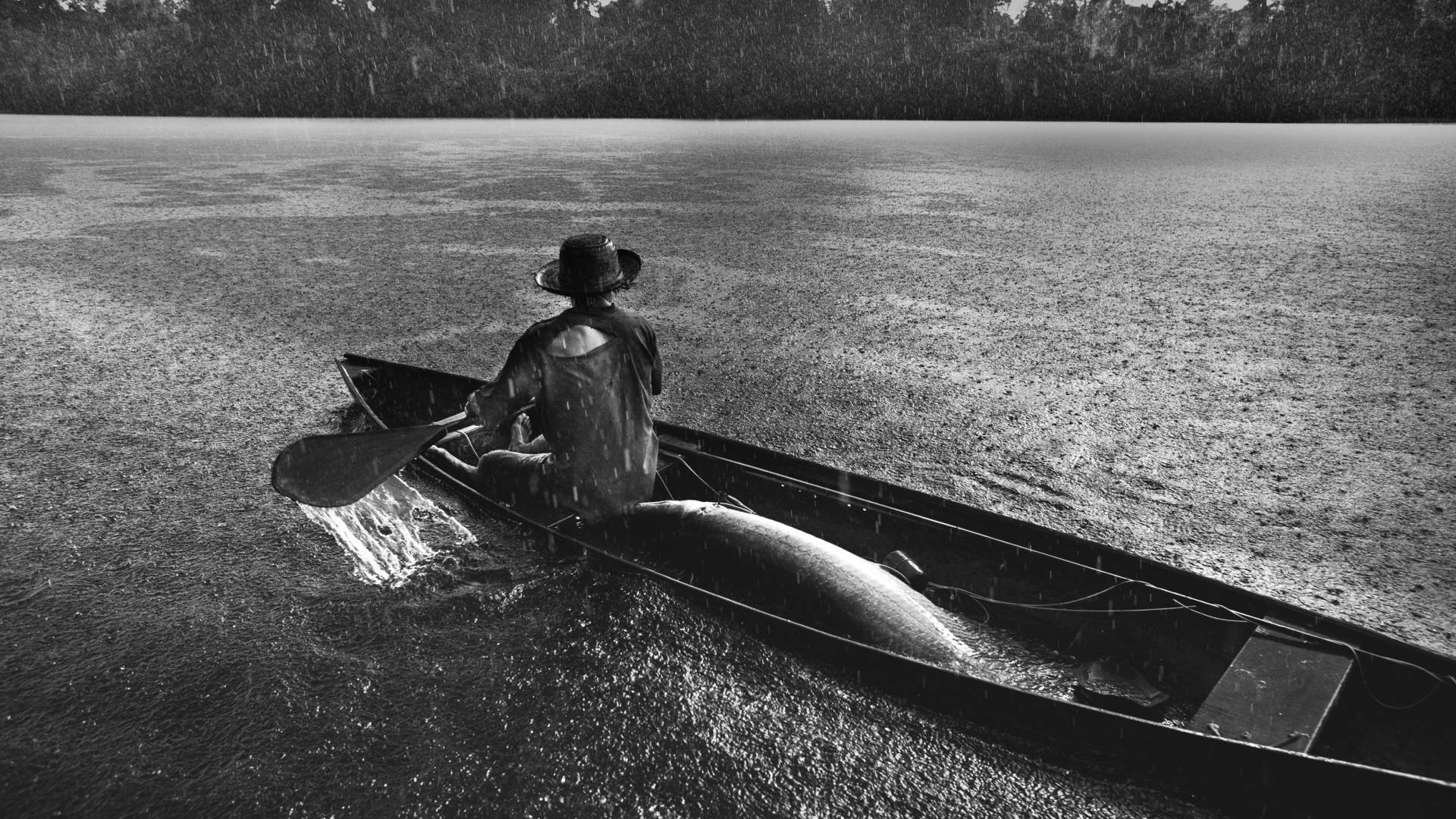

Below, view a selection of photos of the Amazon by Brazilian photographer Araquem Alcantara. Also see his website. Alcantara is preparing a book of his art in English for 2020.

The panel “A World Without the Amazon?” asked the audience to consider the ecosystem transformations and global climate impact of a disappearing Amazon.

Paulo Artaxo, professor of physics at the University of São Paulo, explained that the Amazon region is crucial to the global water cycle and the Earth’s carbon balance. “The Amazon is key to global sustainability,” he said. “And curtailing global emissions is crucial to the survival of the rainforest.”

Elena Shevliakova, physical scientist at the Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory and a visiting research scholar at the Princeton Environmental Institute (PEI), and Stephen Pacala, the Frederick D. Petrie Professor in Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, laid out a worrying, cutting-edge modeling exercise of an Amazon-destroyed world. “We face four major environmental crises in the world now: climate, food, water and biodiversity,” said Pacala. “The Amazon is at the center of all of them.”

“Safeguarding the Amazon and its rich bio-social diversity and environmental services for Brazil and the planet is a key mandate for our times,” said João Biehl, the Susan Dod Brown Professor of Anthropology and director of the Brazil LAB at the Princeton Institute for International and Regional Affairs (PIIRS), in his opening remarks. “It necessitates our very best ideas and practices.”

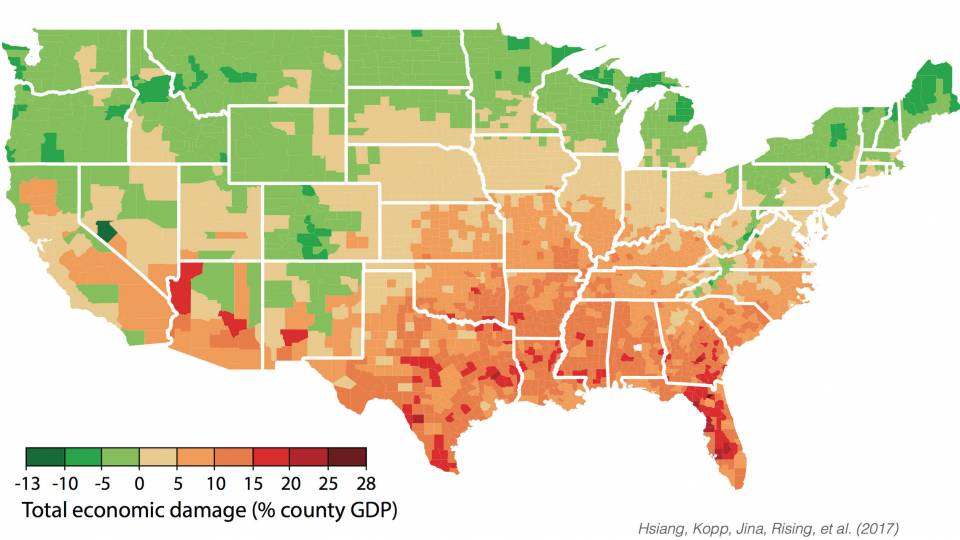

Building on the earlier work of Brazilian climate scientists such as Carlos Nobre, who spoke at the conference, Shevliakova and Pacala modeled the climate impacts by 2050 of deforesting the whole of the Amazon and replacing it with pasture.

If the Amazon disappears altogether, even in the scenario in which the world is able to slash its carbon emissions, average temperatures worldwide would rise 0.25°C beyond the expected increase, the scientists noted. “We will be less likely to reach Paris Agreement goals, including climate change stabilization under 1.5°C,” Shevliakova said. In the Amazonian region, the model indicated that by completely eliminating the forest, the region would get up to 4.5°C hotter, making it practically uninhabitable. The effect on rainfall would be equally catastrophic: on average, it would rain 25% less in Brazil. As Shevliakova stated, “It's a bad story any way you look at it.”

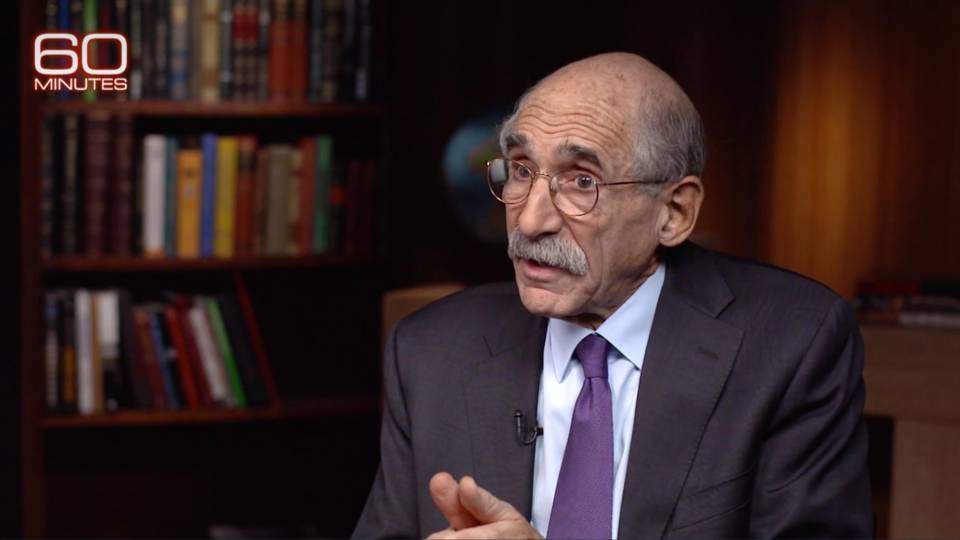

Michael Oppenheimer, the Albert G. Milbank Professor of Geosciences and International Affairs and the Princeton Environmental Institute, parsed the importance of the modeling exercise as a communications and educational tool and discussed policy solutions to deforestation.

Izabella Teixeira, former minister of the environment of Brazil, in conversation with Michael Oppenheimer, the Albert G. Milbank Professor of Geosciences and International Affairs and the Princeton Environmental Institute, parsed the importance of the modeling exercise as a communications and educational tool and discussed policy solutions to deforestation. “Leapfrogging relies, fundamentally, on political will and public investment,” Teixeira said.

The concept of “Amazonian leapfrogging” was inspired by the work of the Brazilian scientist and policymaker José Goldemberg, a collaborator of Princeton’s Robert Socolow, professor of mechanical and aerospace engineering, emeritus, and a conference keynote speaker, who explored Brazil’s capacities for large-scale technological innovations, circumventing inefficient and environmentally damaging paths.

In their welcome addresses, Stephen Kotkin, the John P. Birkelund '52 Professor in History and International Affairs and director of PIIRS, and Michael Celia, the Theodora Shelton Pitney Professor of Environmental Studies and director of PEI who is also a professor of civil and environmental engineering, highlighted that the event was part of an ongoing collaboration between Princeton and multiple Brazilian stakeholders.

In “Amazonia Today,” the conference’s first panel, Tasso Azevedo, a Brazil LAB scholar and coordinator of MapBiomas, a land use mapping initiative that deploys high-resolution satellite images and automated data processing in partnership with Google Earth Engine, presented the latest deforestation data, which he estimates to be about 20% of the Brazilian Amazon, and the impact of out-of-control fires in the region. Azevedo said that over 90% of deforestation is illegal. “This number might even be too conservative.”

Beto Veríssimo, a Brazil LAB scholar and co-founder and senior researcher of the nonprofit Imazon, stressed the need for public and private initiatives that address “the region’s very low socioeconomic indicators and that promote a forest-based economy.” After the screening of his documentary film “Amazonia: The Last Frontier,” the Brazilian director Estevão Ciavatta warned the audience: “We are burning our future.”

In “Amazonia Today,” the conference’s first panel, Tasso Azevedo, a Brazil LAB scholar and coordinator of MapBiomas, a land use mapping initiative that deploys high resolution satellite images and automated data processing in partnership with Google Earth Engine, presented the latest deforestation data, which he estimates to be about 20% of the Brazilian Amazon, and the impact of out-of-control fire in the region.

On Friday, participants were invited to closed-door sessions to engage in dialogue about emergent visions to safeguard the Amazon, addressing issues such as law enforcement, protection of indigenous rights, payment for environmental services, bio-economy, commodity traceability and corporate responsibility. Panelists included Almir Narayamoga Suruí, chief of the Paiter Suruí people who recently created the Suruí University; Helder Zahluth Barbalho, governor of the State of Pará; Roberto Marques, CEO of Natura & Co.; Luiz Cornacchioni, executive director of the Brazilian Agribusiness Association; Ilona Szabó, director of the think-and-do-tank Igarapé; Hugo Aguilaniu, president of the scientific foundation Serrapilheira; and Luciano Huck, a television show host.

“The complex Amazonian ecosystem transformations and the region’s dire social realities require collaborative and innovative ways of thinking and doing, and it is wonderful to see Princeton as a core hub for this timely work,” stated Biehl at the end of the event.

The conference highlighted the importance of science and critical story-telling for public mobilization and left the participants with an ask of what they — both as representatives of their sectors and collaboratively — can do to better manage resources, support vital policies, and act strategically to address the socioenvironmental challenges of today and of the future.

The conference was organized by the Brazil LAB, together with the Princeton Institute of International and Regional Studies and the Princeton Environmental Institute, and was co-sponsored by the University Center for Human Values and the Program in Latin American Studies.

On Oct. 18, participants were invited to sessions to engage in dialogue about emergent visions to safeguard the Amazon. Almir Narayamoga Suruí, chief of the Paiter Suruí people who recently created the Suruí University, speaks to Brazilian lessons for the Amazon.