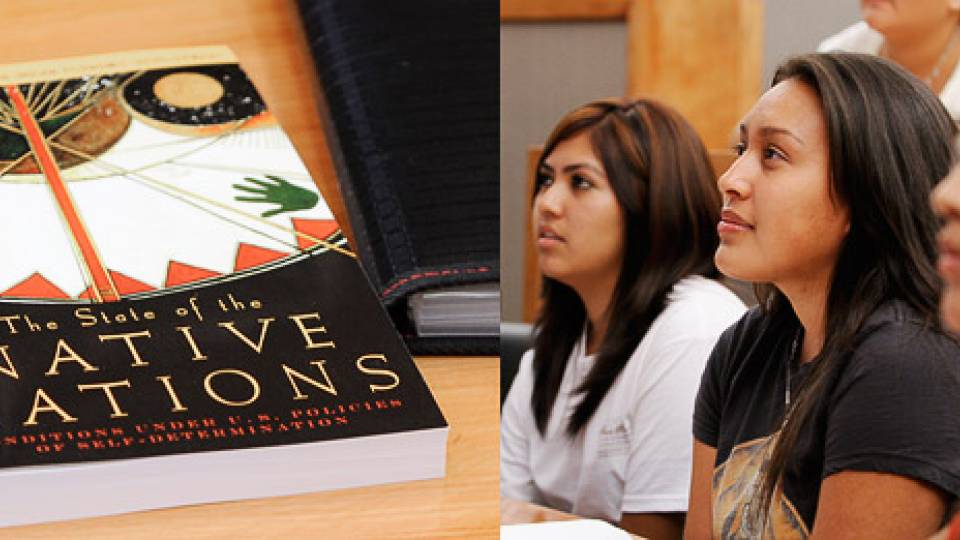

Faculty leader Amanda Montoya (center), the executive director of the Chamiza Foundation who is from the Taos Pueblo, and students in the Santa Fe Leadership Institute's Summer Policy Academy participate in a team activity addressing issues related to education, community planning, climate change and sacred site protection.

Looking at a photograph of a single plant surrounded by towering weeds, 14 Native American high school students from New Mexico discussed the parallels between nurturing and maintaining crops and strengthening their own communities.

Together, the students brainstormed ways to remove barriers affecting their communities such as substance abuse, obesity and lack of cultural education.

“For our children to have successful lives, you have to remove the barriers, like removing weeds,” said Tonesha Coriz of the Santo Domingo Pueblo. “This starts with education — not only in the Western world, but also in the Native American world.”

Coriz is one of several Native leaders who facilitated discussions and gave presentations during the Santa Fe Leadership Institute’s Summer Policy Academy (SPA), hosted by Princeton University’s Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs.

The academy, which took place the week of June 16, focuses on contemporary challenges and federal policies affecting Native American communities. Students are selected for the program after being nominated by their teachers, community leaders, business professionals and tribal leaders. Each student represents a different Native American community in New Mexico.

“In society we sometimes ignore the voices of young people and disregard them as being either naive or not equipped to handle the complexities of all these issues that we’re dealing with,” said attorney Casey Douma, a faculty member in the program for the past 13 years. “But we see that if you take young people seriously, listen to them and equip them with the ability to research to explore these issues, many of them have solutions that can create the necessary change in our communities as well as in the country.”

Programming focused on health, environment, education and language. Participants worked in teams to address policy topics pertaining to their communities, including Native American education, community planning, climate change and sacred site protection. After the week in Princeton, the students traveled to Washington, D.C., to present their research and policy recommendations to congressional delegates representing New Mexico.

SPA was co-founded and is co-directed by Regis Pecos, a 1977 Princeton alumnus, a former University trustee and former governor of the Cochiti Pueblo, and Carnell Chosa of the Jemez Pueblo.

The goal of the program is for students to “understand and appreciate how the challenges we face in our communities, at the state and national levels, are deeply embedded in the history of the policies and laws intended to assimilate us,” said Pecos. “How we respond to these challenges requires that we become authors and architects of policies and laws guided by our core values to protect our way of life and sustain who we are by balancing indigenous knowledge and western education.”

The program educates students about the history of their cultures not taught in a high school curriculum, so that they can understand current challenges in their communities. Gaining this knowledge is “how we learn to love our languages, our culture, our lands and our people — to do what is necessary to protect and sustain all that defines who we are,” Pecos said.

“My community means a lot to me because of the language and traditions we participate in,” said Keithan Shendo, a student from the Jemez Pueblo. “We are the only Towa-speaking community in New Mexico. I don’t want to lose the language, but with all of the issues we are facing, it feels like we are.”

Shendo said the SPA program has helped him consider ways to teach the younger generations how to love and respect their native language to prevent language loss and strengthen their culture.

Douma said the voices of Native people are not heard in policymaking, but the students and faculty are motivated to make sure their voices are heard. The program embraces their Native American identities and strengthens their role in effecting change.

Ethan Roanhorse, a student from the Navajo Nation, appreciates how SPA focuses on the youth.

“[The SPA faculty] have shown us from the start that it’s going to be our future and we’re ‘the future,’” said Roanhorse. “I was not really much of a leader until I came to SPA. Now I am here, I think a little bit more of my call to help my Indigenous people.”

Celeste Lucero (left) of the Isleta Pueblo, Clarissa Abeyta of the Isleta Pueblo and Keithan Shendo of the Jemez Pueblo practice presenting their research and policy recommendations prior to a group trip to Washington, D.C., to meet with congressional delegates representing New Mexico.

Holding SPA at Princeton also allows the students to experience new perspectives outside their home communities. According to Douma, the students, who sometimes feel misrepresented across institutions of higher education, leave the program feeling more comfortable in university settings such as Princeton.

“Sometimes there’s this feeling of inadequacy — like we don’t belong because we don’t share the similar background or experiences as others,” Douma said. “Having this relationship with Princeton allows our students to feel and see their place in these institutions and know that they do belong, they have value, and they can contribute a lot to the overall diversity of thought that these institutions have.”

SPA is designed to motivate students to continue to find new solutions for their communities long after they leave Princeton and return home to New Mexico. Reflecting on his experience in the program, Shendo said he and all Indigenous people want others to know: “We are still going strong in our community. We are still fighting for what’s ours and what’s right for us.”

Students take a break with 1977 Princeton alumnus Regis Pecos (center), co-founder and co-director of the program.