Students focused on challenges and federal policies affecting Native American communities during this year's Santa Fe Indian School Leadership Institute's Summer Policy Academy hosted at Princeton's Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs. They were guided by instructors Regis Pecos, Class of 1977 (front row, far left), Dr. Amanda J. Montoya (front row, second from left), Christie Abeyta (second row, far left), Patrice Chavez (third row, far left), Casey Douma (third row, third from left), and Aaron Sims (third row, fifth from left).

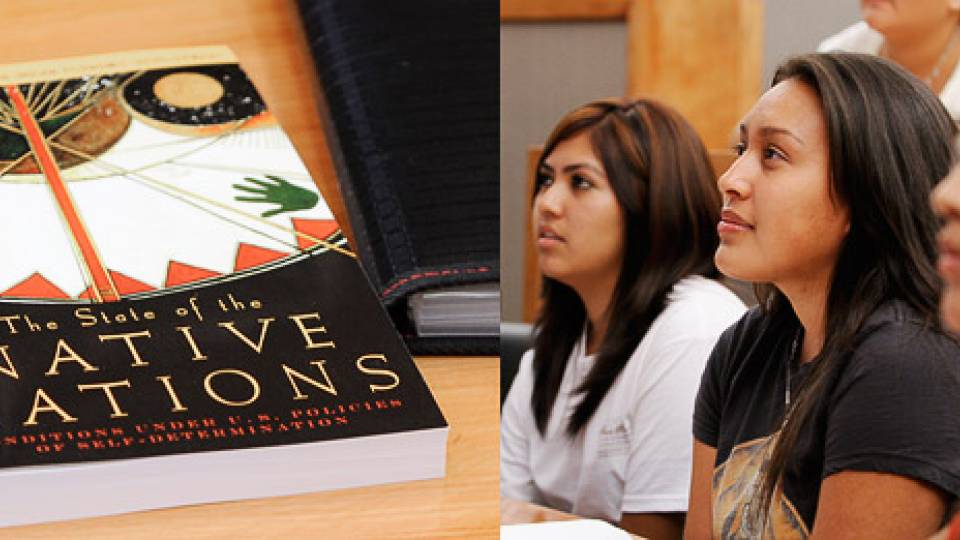

Seventeen high school and college students from a diverse group of indigenous tribes in New Mexico arrived at Princeton on June 9 for a weeklong program focusing on contemporary challenges and federal policies affecting Native American communities.

This year marks the 11th annual Santa Fe Indian School Leadership Institute’s Summer Policy Academy (SPA), hosted at Princeton University’s Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs.

Students are selected to participate in the SPA after being nominated by their teachers, community leaders, business professionals and tribal leaders. Through discussions, case studies and presentations by Native leaders and academics, participants focus on issues related to education, language, environment and health.

To translate what they learn in the classroom to the real world, students form teams to research and present on policy topics relevant to their communities, such as new strategies in Indian education; protection of the Chaco landscape; and higher education, workforce development, and community planning. At the end of the week, they travel to Washington, D.C., to present their findings and policy recommendations to United States senators and members of Congress representing New Mexico, as well as officials from the National Congress of American Indians and the National Museum of the American Indian.

Instructor Christie Abeyta, of the Santa Clara/Santo Domingo Pueblo, leads Native American students in a policy discussion in Robertson Hall.

The SPA program was co-founded and is co-directed by Regis Pecos, Class of 1977, a former Princeton trustee and former governor of the Cochiti Pueblo, and Carnell Chosa of the Jemez Pueblo.

According to Pecos, “the vision and purpose of this program is to provide young Natives with the opportunity to learn about the history and the policies and laws that have affected their communities.” Many of the issues and challenges the students learn about are not part of the public school education system, Pecos said.

Since Native American students are underrepresented across institutions of higher education, the fact that they can “observe and experience” a prestigious institution like Princeton University is life-changing, Pecos said. “It’s humbling to have this partnership with the Woodrow Wilson School, a place revered for nurturing minds in public policy,” he added.

Over the years, SPA has provided nearly 300 Native American students with opportunities that have helped to inform their career paths, and almost all SPA alumni are working in some capacity to support their tribal nations, Pecos said.

Charles Padilla of the Zuni Pueblo, a sophomore at the Institute of American Indian Arts, said the program has “shifted” his thinking, and now he is considering attending graduate school. “Policy was never something that I wanted to pursue in higher education, but spending time at the Woodrow Wilson School has changed my mind,” Padilla said.

Another SPA fellow, Evangeline Nanez of the Acoma Pueblo, said she attends a public high school in Albuquerque, where the curriculum does not focus on Native American history or culture. SPA helped her and many of her peers learn about their own communities, language and history. Through this program, Nanez said, she’s “learned about who [she is] as a Native person.”

Nanez plans on attending college and wants to study environmental science or developmental psychology.

Seventeen high school and college students from indigenous tribes in New Mexico participated in the academy.