Professional football player and activist Michael Bennett talks about sports and the black experience at a March 11 public conversation in Richardson Auditorium.

Professional football player and activist Michael Bennett is used to crowds of thousands in stadiums. On March 11, he greeted a slightly smaller, but no less enthusiastic crowd in Richardson Auditorium at Princeton as he settled into a leather armchair.

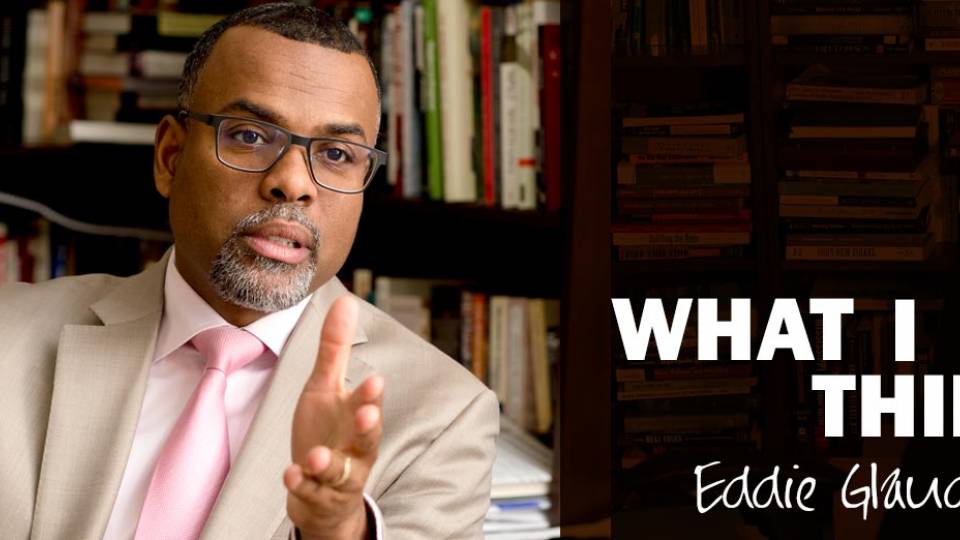

Bennett, a defensive end who made sports headlines last week when he was traded from the Philadelphia Eagles to the New England Patriots, flexed a different set of muscles on the Princeton stage. In a wide-ranging conversation, Bennett and Eddie Glaude Jr., the James S. McDonnell Distinguished University Professor, professor of religion and chair of the Department of African American Studies, explored the influence and relationship of the NFL to issues around race and the black experience.

Bennett and Eddie Glaude Jr., the James S. McDonnell Distinguished University Professor, professor of religion and chair of the Department of African American Studies, explored the influence and relationship of the NFL to issues around race.

The event was the latest in the Sports, Race and Society Lecture series, made possible by the Stephen C. Mills ’81 Fund. Glaude said the idea for the series “was to build a bridge between African American studies and the athletics department, to create a public forum to think seriously about the role of sports and elite athletes in our society, and to explore with nuance and care how race shapes that world.”

Glaude said Bennett fits this vision perfectly. “Michael Bennett has emerged as one of the most important political voices in sports today. He speaks his mind boldly, always with a sense of humor and with a deep commitment to a more than just society.”

Bennett is well-known both on and off the football field. A three-time Pro Bowler, Pro Bowl MVP, Super Bowl Champion and two-time NFC Champion, Bennett has gained international recognition for his public support for the Black Lives Matter Movement, women’s rights and other social justice causes.

He is the co-founder with his wife, Pele Bennett, of The Bennett Foundation, which educates underserved children and communities through free, accessible programming. He has held free camps and health clinics in Seattle, in his hometown of Houston, in his current offseason home, Honolulu, and in South Dakota on the Lower Brule Sioux Tribe. He donates all of his endorsement money and the proceeds from his jersey sales to fund health and education projects for poor and underserved youth and minority communities, and recently expanded his reach globally to support STEM programming in Africa.

Glaude set the tone of the conversation with candor and humor.

Glaude said the event, the latest in the Sports, Race and Society Lecture series, was part of a goal to "create a public forum to think seriously about the role of sports and elite athletes in our society, and to explore with nuance and care how race shapes that world.”

“Let’s get the elephant out of the room. You’re going to the New England Patriots,” he said, eliciting audible sighs of disappointment from Eagles fans in the audience mixed with cheers from others, then laughter from all.

“I get to be with one of the brightest minds in football with [coach Bill] Belichick,” Bennett said, grinning widely. “I know everybody hates [Patriots quarterback] Tom Brady but everybody hates a winner,” eliciting more laughter.

Glaude turned the focus to Bennett’s childhood in rural Louisiana, which he describes in his 2018 memoir, “Things That Make White People Uncomfortable.”

The eldest of five children, he learned the importance of family from planting watermelons, red bean, okra and tomatoes on his grandfather’s farm. “When I think about immigration issues, when I see people who work on farms picking bell peppers, when I see that job, I understand my work ethic.” Looking at the audience, he said: “Never look down on a person because of their job … that person is earning an honest living. That taught me compassion for others, and I’ve always kept that inside of me.”

His father, Michael Sr., was seated in the front row. “Most of my friends didn’t have a father,” he said. “He shaped me as a parent and as a man. At college, my coaches perceived me as a young black man without a father. … My father was very dynamic in my life, a shining light to help me make decisions.”

Though his parents divorced when he was young, Bennett said he was close with both. “My mom is the epitome of what a strong black woman is,” he said. From his stepmother, Pennie, a junior high school teacher, Bennett learned “everything was about education.”

He said his brother — former New England Patriots tight end Martellus Bennett, who is reportedly considering coming out of retirement to play on the same team as his brother — is his best friend. “We talk five times a day. I’ve been so blessed.”

The book exposes what happens to professional athletes after they retire or can’t play anymore because of an injury, many of whom suffer depression and post-traumatic stress disorder. Bennett said he wanted to challenge his readers to consider what happens when their heroes on the field or on the court fail.

“Are your fans there when you break your leg and all your dreams are lost? I wanted people to see an athlete not just as this thing that can do amazing things with a ball but as a human. … That’s the part of sports we don’t talk about,” he said.

He writes about Kansas City Chiefs’ Jovan Belcher, who killed his girlfriend then committed suicide in 2012. “I wanted the reader to really grasp that moment. Jovan Belcher blows his brains out… When you get to these moments, the fans don’t connect anymore.” He said he wanted to “put a human face” on these issues.

“You never have been soft-spoken about race,” said Glaude, noting Bennett’s open criticism of the NFL.

In the book, he compares the physical assessment of players entering the NFL to the slave trade. “They weighed slaves, checked how big their feet are, said ‘this is a work horse’ or ‘this is a stallion.’ The NFL checks everything [too],” Bennett said. “I wanted to talk about that.”

He also wanted to draw attention to inequality at the highest levels in professional sports. “We think because there are blacks on the field we’re integrated, but we need to see that at the executive level,” he said, calling not only for more black coaches, referees and CEOs, but also women. “It’s important as an athlete to keep pushing that agenda.”

“So you took the knee?” said Glaude, referring to Bennett’s solidarity with former San Francisco 49ers quarterback Colin Kaepernick, who started a wave of protest by refusing to stand during the national anthem in 2016 because of his views on the country’s treatment of racial minorities.

“I just sat down on the bench,” Bennett said, eliciting applause from the audience.

“What was the reaction?” Glaude said.

The enthusiastic crowd takes in the conversation, which was followed by a Q&A session.

Some people felt he was disrespecting the flag, Bennett said, while others focused on the issue of police brutality. “But it was about everything — Haiti, being Native American, not just one singular thing. It was the first time athletes had been heard on an intellectual level.”

Wrapping up the conversation before the Q&A, Glaude read a short passage from Bennett’s book, ending with, “You have to open yourself up and get comfortable with your discomfort, then you don't need to build more walls. Instead they just come tumbling down.”

Glaude said, “Talk to me about this insistence on not being boxed in.”

It’s all about his three daughters, Peyton, Blake and Ollie, Bennett said.

“First, they're women, then they're women of color, there are so many different things that are boxing them in. And for me, that's the reason why I do everything because I want them to look back and [say], ‘My dad never—.'" Bennett stopped for a long moment, the fingers of one hand resting against the bridge of his nose, hiding his eyes. His voice choking with emotion, he resumed. "—he never stopped, he always kept going, he always pushed the agenda forward. That's pretty much why, that's the reason why I'm existing, because of them, really."