This summer, 24 rising sophomores participated in a language immersion program in Aix-en-Provence. While they enrolled in the program to improve their command of the French language, they left with a deeper understanding of how language intersects with social, political and cultural issues.

Aix-en-Provence, or Aix, is an ancient city in the South of France famous for its fountains, its markets and the French painter Paul Cézanne. Once the capital of old Provence, the city has been a university town since the Middle Ages and is home to a number of schools, or “écoles,” whose 30,000 students contribute to the town’s intellectual vibrancy. Its museums, music festivals and Provençal character draw people from all over the world to Aix, making the city a hub of culture in Southern France.

These are some of the reasons that Christine Sagnier, director of the French language program and senior lecturer in French and Italian, chose Aix as the location for the French study abroad program 11 years ago. This year, she added a new area of focus to the program: an ethnographic project titled “Voices in the City,” which offered an introduction to fieldwork in sociolinguistics.

“I wanted students to have opportunities for ‘learning by doing,’ spending as much time as possible outside of the classroom through activities designed to help them experience, experiment, observe and critically reflect,” said Sagnier. “In a smaller setting such as Aix, it is easier to interact with the community than in a large city.”

The ethnographic project is one component of the four-week program, designed to give students an immersive linguistic and cultural experience in a scenic French locale.

“I chose to study abroad in France because I wanted the experience of being able to learn through immersing myself fully in a language,” said Jena Yun. “This opportunity was also a chance for me to travel to Europe for the first time.”

Paige Allen agreed: “I knew my proficiency would improve significantly after four weeks of speaking only French. I also couldn't pass up the chance to visit such an incredible country; it's truly a beautiful place!”

A home away from home

Before their arrival, students sign an honor pledge to speak only French, even among each other. Each student stays with a host family, many of whom go above and beyond to show their guests all that Aix has to offer.

Over the years, many Princeton students have developed long-term relationships with their host families, sometimes calling them “my French Mom or Dad”; some even return to see their former hosts in Provence years after they have graduated.

“I had a great relationship with my host family,” said Kyle Johnson. “All of the food the family prepared was made from scratch and they were so helpful in practicing French and adjusting to life in Aix.”

“My host mom was lovely, and she didn't speak any English, so my French improved a lot!” said Myrha Qadir. “One of my favorite memories is going bowling together — I won!”

Anna Vinitsky’s host father was adamant that she not leave Aix without hiking to the top of Mount Sainte-Victoire, the mountain immortalized in Cézanne’s paintings. “It was a difficult trek, and we made several stops to munch on ‘les biscuits’ and discuss the beautiful scenery around us,” said Vinitsky. “The view from the top was breathtaking and made the early start and arduous climb more than worthwhile.”

The city as a classroom

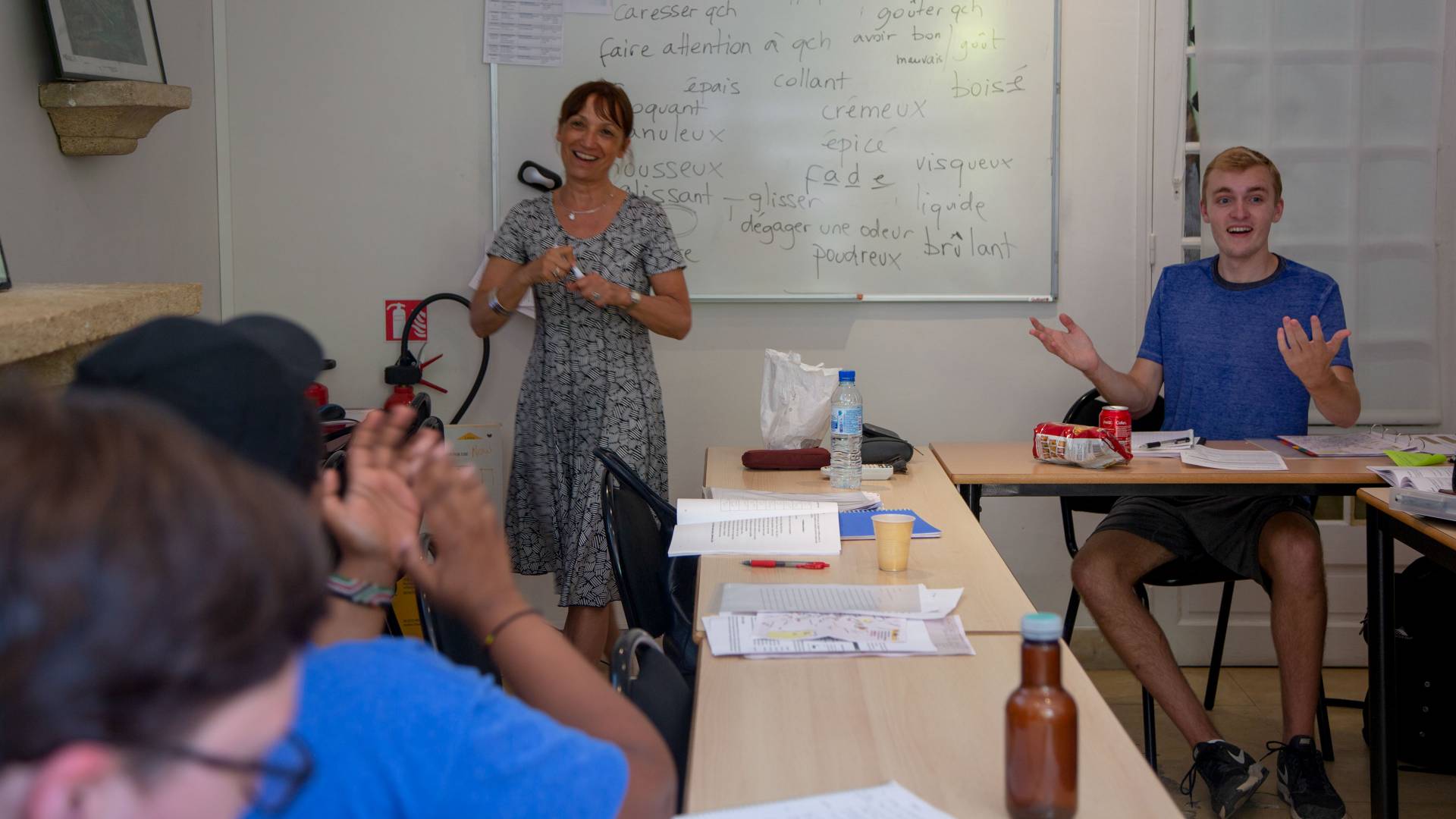

Students attend classes at IS Aix-en-Provence, which is housed in a former private mansion close to the town center (directly above). In the classroom, students work on their oral comprehension and expression through activities led by French instructors Claire Auzeville and Naïma Chetioui.

Sagnier and Murielle Perrier, the program’s associate director, lead workshops on the theme of the five senses, helping students to better express themselves in French through creative writing activities that draw on their sensory experiences in Provence. The class also reviews French journalistic texts and reflects collectively on their editorial composition and structure.

As Pamella Uwase observed, however, much of the learning happened outside of the classroom. “I was thinking that we were going to spend a lot of time in class, but we ended up spending much more time outdoors, experiencing French culture.”

The program’s cultural immersion experiences included a cooking class with a local chef, where students prepared a Provençal meal of ratatouille and “sablés aux fraises a la crème,” or butter cookies with fresh strawberries and cream, before enjoying their creations at a group dinner.

Through a collaboration with a nonprofit art gallery, Gallery 361, students also worked with local artists on a project titled “Art et Langue,” or “Art and Language,” initiated by French instructor Chetioui. After creating abstract paintings, urban art, sketches and sculptures, the project culminated with a private viewing in the gallery, where students presented their creations in French.

The ethnographic project “Voices in the City” bridged the students’ classroom learning with a chance to explore the city and engage with “les Aixois,” or residents of Aix, firsthand.

“The program has always emphasized the importance of journalistic writing; this year, we wanted to shed light on Aix’s ‘linguistic landscape’ by giving the students an opportunity to conduct their own ethnographic work,” said Sagnier.

As she explained, Provençal had been the city’s regional language for centuries. Today, the language is hardly spoken or heard, yet references to its existence are still omnipresent in Aix, visible on things like street signs.

To learn more about the discrepancy between the displayed language and the realities of the Provençal dialect for Aix’s residents, students prepared their own questions and used a sociolinguistics questionnaire written by Sagnier to interview their host families and a diverse group of “les Aixois.”

The students were surprised by the results. “Following our in-class discussions of the significance of Provençal and the measures the government was taking to preserve the language, it was almost jarring to speak to my host family and the other Aix residents I interviewed,” said Glenna Jane Galarion. “It was evident that there was a disconnect between official and unofficial sentiments towards the language within the city; although the government instituted numerous measures to maintain the presence of the language within Aix, the general sentiment shared by the public was that the language was a dying dialect.”

She added: “To residents, Provençal is a mode of life, rather than an official language.”

Tatijana Stewart came to a similar realization. “The citizens of Aix are choosing to preserve Provençal culture by embracing ways of marketing it to the regional and global communities who visit Aix.” She cited the owner of a traditional soap-making shop whom she interviewed for her ethnographic project as an example. “By doing things like renovating the interiors of public buildings to keep up with changing demands, the people of Aix are contributing to the protection and promotion of Provençal culture — it's just not the more obvious language-based role that I was expecting when we first began our projects.”

Students were also surprised by the extent to which globalism has impacted Aix. “There were so many signs in English aimed at tourists, like a restaurant was top-rated on TripAdvisor, next to authentic French institutions like Béchard; it was quite an interesting juxtaposition,” said Johnson.

“I had never realized how many different languages were spoken in France before coming to Aix. The linguistic landscape is so much more diverse than I thought,” said Qadir.

Princeton partnered with the Aix-Marseilles University sociolinguistics department to enhance the Princeton students’ experiences in Aix and Marseilles. In this photo, the group leaders take a break from the heat at a café in Aix. From left: Sylvie Wharton, Murielle Perrier, Heloïse Giese, Fathia Benali, Médéric Gasquet-Cyrus, Christine Sagnier, Fatine Kahli, Rhian Wolstenholme.

A tale of three cities

Students got an even deeper understanding of this sociolinguistic diversity through day trips to two other Provençal cities, Arles and Marseilles, which enabled them to compare and contrast their findings in Aix.

Thanks to a new partnership between Sagnier and two researchers from the University of Aix-Marseilles, Sylvie Wharton and Mederic Gasquet-Cyrus, Princeton students benefited from the expertise of graduate students at Aix-Marseilles University, who accompanied them on fieldwork in different neighborhoods.

In Arles and Marseilles, students observed the urban landscapes for the presence of minority languages, collecting data on public signage and official displays, as well as traces of unofficial “voices in the city,” such as graffiti, looking at ways in which the public space is symbolically constructed, and reflecting on the configurations of the cities they visited.

“The work we did in the course allowed me to understand some of the demographic breakdown in France, specifically in Aix and Marseilles and more generally the southeastern French area, and how language intermingles with these concepts both on a psychological and systemic level,” said Erica Dugué.

“I found each town's unique identity particularly interesting,” said Stewart. “Geographically speaking, Marseilles and Aix aren't so far apart, yet they have such different vibes and values; that really seemed to be the case with every town we visited on our excursions, big and small alike.”

“There is always so much more to learn”

With the help of Ben Johnston, senior educational technologist at the McGraw Center for Teaching and Learning, Sagnier launched an interactive website for students to upload their data and post their ethnographic interviews and personal reflections throughout the course.

The program culminated with student presentations of their ethnographic projects, which many students have continued reflecting on after the program’s end.

“The ethnographic project helped dispel the idyllic image I had in mind when I thought of Provence as a region, and it opened my eyes to the grittier realities of balancing the welcoming of immigrants with their assimilation into the culture,” said Regina Lankenau. “It's an issue I had seen on the news, but it didn't feel concrete until I saw the traces of that struggle on the graffitied walls of Marseilles.”

“After this class, I've noticed myself observing places I visit more critically and thoroughly. I'm starting to notice more about the writing, the people, the buildings, and am starting to think more about what each of these things mean or add to the overall identity of each space,” said Stewart.

Another important takeaway from the program? “There is always so much more to learn,” said Allen. “There are always more vocabulary words, more idiomatic expressions and more subtleties of culture to try to understand. That being said, I did feel very proud by the end of the experience. I feel like I truly improved my listening and speaking skills, and I was able to compose creative and journalistic writing in French that didn't feel like it was at a lower level than similar assignments in English. As a writer, that meant a lot to me!”

The group poses for a picture atop the Roman amphitheater in Arles, France.