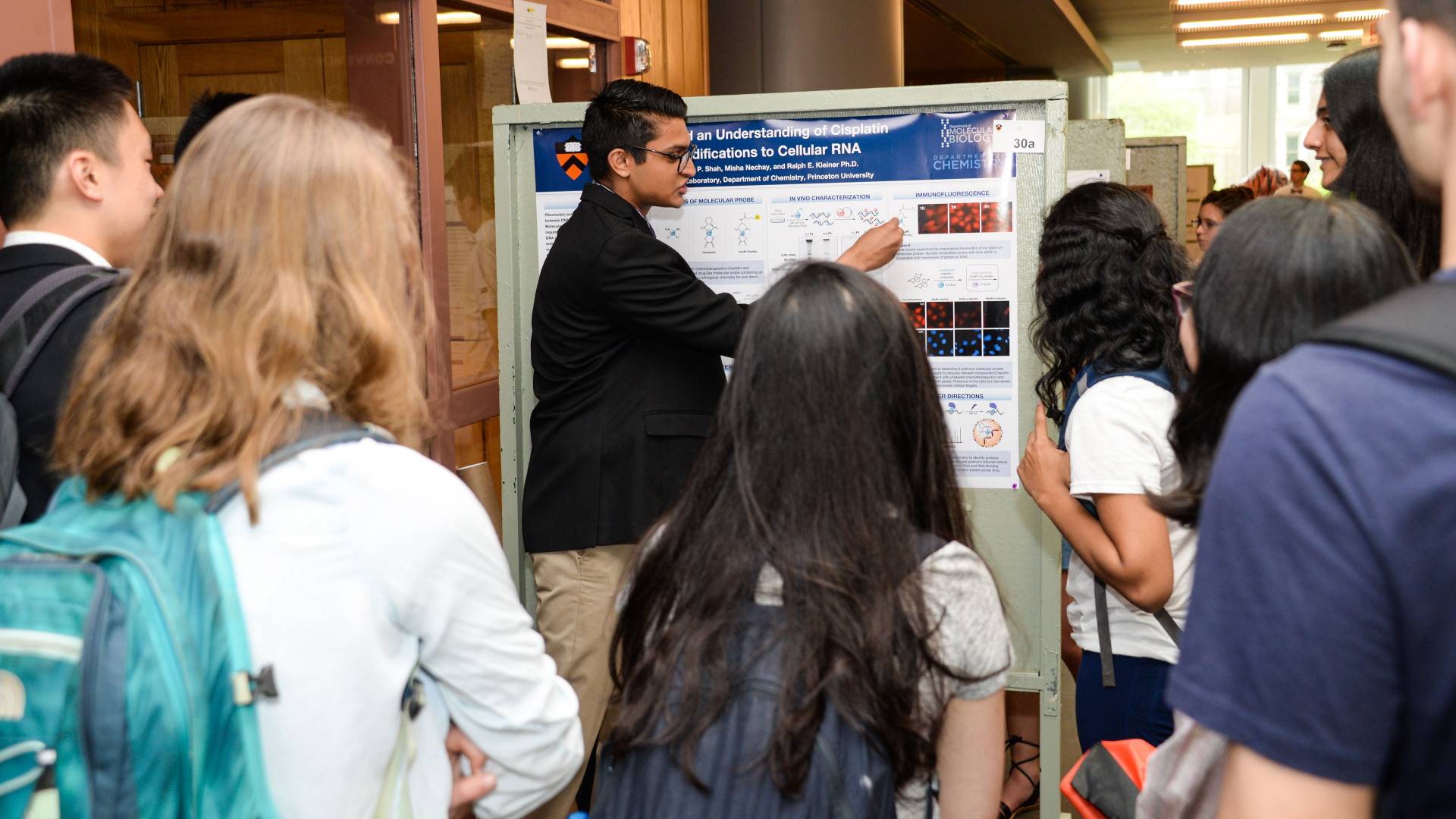

The University's annual Princeton Research Day allows researchers from across the disciplines to present their work to the public. Here, sophomore Rohan Shah presents his poster titled “Toward an Understanding of Cisplatin Modifications to Cellular RNA.” The event was held May 10 in Frist Campus Center.

Spend the day — or an hour — at Princeton Research Day, and you get an eclectic tour of research at Princeton University shared through presentations designed to make cutting-edge work accessible to the general public.

For Sarah-Jane Leslie, dean of the Graduate School and the Class of 1943 Professor of Philosophy, that tour included learning how engineers can learn lessons from plants; about new techniques to fight disease; and about novel ways to address the world’s energy crisis.

Speaking at the event’s concluding awards ceremony in Frist Campus Center on Thursday, May 10, Leslie said she came away thinking that “Princeton students and researchers might just save the world.”

The third annual event featured more than 190 talks and posters by undergraduates, graduate students, postdoctoral researchers and other campus researchers from engineering, social sciences, natural sciences, humanities and the arts.

At the awards ceremony, Jill Dolan, dean of the college, the Annan Professor in English and professor of theater in the Lewis Center for the Arts, tells participants and audience members that all research needs to be communicated broadly to be effective.

“Princeton Research Day is an incredible display of the breadth and the vitality of Princeton’s research enterprise,” said Pablo Debenedetti, dean for research, the Class of 1950 Professor in Engineering and Applied Science, and a professor of chemical and biological engineering.

Provost Deborah Prentice, the Alexander Stewart 1886 Professor of Psychology and Public Affairs, emphasized the University’s commitment to research and said, “This gives us an opportunity to celebrate it.”

Princeton Research Day is a collaborative initiative by the offices of the Dean of the College, the Dean of the Faculty, the Dean of the Graduate School and the Dean for Research, with support from the Office of the Provost. Sixty graduate alumni, 50 undergraduates and 70 faculty, staff and community members served as judges for the event, and more than 150 volunteers helped everything run smoothly for the presenters and hundreds of attendees.

Writers for the Princeton Correspondents on Undergraduate Research blog fanned out during the day and offered their perspectives on the event, sitting in on each of the presentation types: 90-second elevator pitches, 10-minute talks, 15-minute PRD Talks and posters. Here are their reflections:

Chemical and biological engineering graduate student Lena Barrett gives her talk, “Stiff Airways May Exacerbate Asthma,” on her work to improve the understanding of how asthma develops.

Session: “Elevator Pitch II”

In the session "Elevator Pitch II," presenters were asked to provide the most intriguing and enticing description of their research in a mere 90 seconds. It was incredible to see how much information presenters were able to squeeze into such a short period of time and provide plenty of fodder for the questions-and-answer session that followed.

Topics ranged from cybersecurity to mental health reform to simulating the earth’s magnetic field fluctuations. The research was also presented from many different stages in the research process — from complete senior thesis research, intriguing leads from junior paper research, and the beginnings and snippets of graduate dissertations.

As a result of this variation, each presentation focused on a different aspect of research. The senior thesis presentations tended to highlight the results of research projects — how to protect anonymous search engines from privacy breaches, the importance of pastors and church communities in urban areas with high rates of mental illness, and the best simulations to model extreme localized fluctuations of the Earth’s magnetic field.

However, other projects that were not as full-fledged, such as junior paper research, focused more on the limitations and future directions for research, such as discovering a surprising and interesting gender difference in people’s views of their friends.

Finally, presentations on just the beginnings of large projects — like dissertations — focused primarily on the methods of the research. One presentation was especially interesting in the sense that it was unexpected to listen to a research presentation completely about methods, in this case analyzing notes in the margins of ancient Yemeni manuscripts.

Having such little time to present research means you can only include the most central aspect of a research project. The choice to focus on methods made me rethink how we often stress the importance of results. While such results are often thought-provoking, they may not always be the most interesting or influential aspect of the research process.

— Ellie Breitfeld, Class of 2020

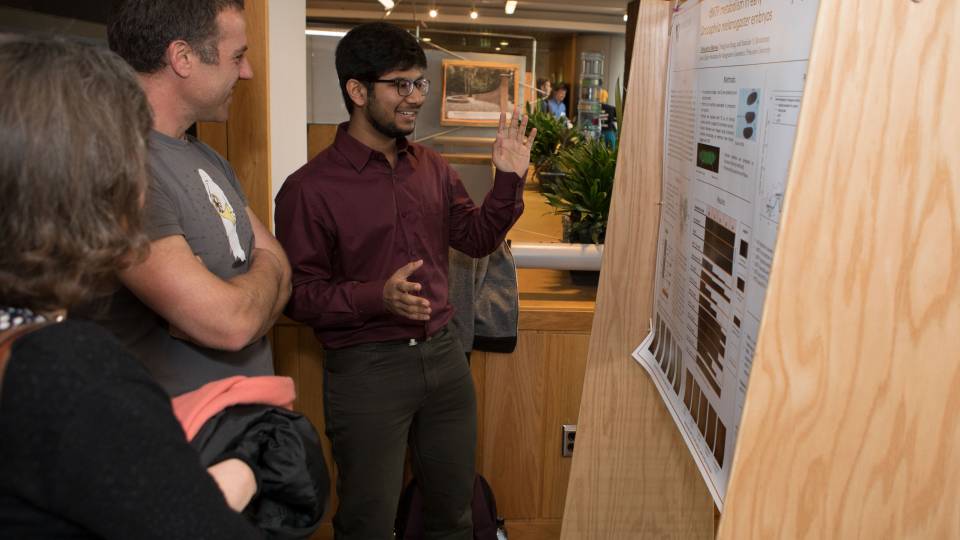

Undergraduates, graduate students and other researchers filled the main atrium of Frist Campus Center with 72 posters exploring research from across the University.

Session: “On the Move”

As the session’s title, "On the Move," would suggest, these 10-minute talks focused on movement-related research. The talks featured presenters from a range of departments (chemical and biological engineering, politics, operations research and financial engineering, and French and Italian), as well as a range of education levels (three undergraduate students, one graduate student and a postdoctoral researcher).

I found each of the talks to be engaging on its own — all of the presenters did a commendable job of clearly articulating their ideas and making their findings accessible to the audience. What struck me the most about “On the Move,” however, was the way in which the four talks found common ground despite the range of disciplines represented.

In the first talk, “Using Drying to Heal Cracks in Soft Materials,” chemical and biological engineering graduate student Nancy Lu and postdoctoral researcher Jeremy Cho discussed their research on how to model, understand and control cracking in clay. Lu and Cho explained that clay cracking is a serious practical issue because clay often fills important roles, such as serving as the foundation of a building or as a nuclear waste container.

Deniz Cekirge, a senior in operations research and financial engineering, presented the third talk, “Maximizing Safety, Minimizing Cost: A Long-Term Solution to Syrian Refugee Crisis through Optimization.” Cekirge explained how she attempted to determine the best location for refugee camps with a cost-minimization model while taking into account safety concerns.

I was struck by how these two talks, despite their disparate subject matters, addressed markedly similar issues and invoked similar strategies for solving them. Both framed movement in terms of a destabilization problem that can be modeled, and both used their models to mitigate the destabilizations’ negative consequences. For me, these two presentations underscored how models and thoughtful research designs can transform problems on both a small scale (like cracking in clay) and a large scale (like mass migrations of people) into concepts that are easier to understand.

— Emma Kaeser, Class of 2018

Senior Soléne Le Van, a French and Italian major, discusses her poster, “Music as Intangible: Arthur Rimbaud and the Antithesis of Representational Poetry,” with judges.

Session: “PRD Talk II”

On Friday afternoon, I observed two 15-minute PRD talks in Frist Theater: “Popular Science and Literary Criticism” by Elspeth Green, and “Design, Construction and Supersonic Wind Tunnel Testing of an Aerospike Rocket Nozzle” by Isabel Cleff. Green is a Ph.D. student in the Department of English, and Cleff is a senior in the Department of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering.

Though totally different, both of their research projects were fascinating, and I loved hearing about exciting new work outside of my own field [social sciences]. But what impressed me most was their dazzlingly polished and gripping presentations.

Speaking to a diverse crowd, the presenters engaged everyone in their talks — from established scholar to total beginner. For beginners, they not only provided the requisite background information for their projects, but also advocated for the importance of their guiding question. Within the first few minutes, they convinced me that their research was important not just for their field, but for me. At the same time, though, they did not reduce the sophistication of their material — engaging with scholars while still empowering a beginner like me to invest in their work.

Additionally, both used clever visuals in their presentations. In fact, they completely avoided the all-too-familiar PowerPoint drowning in text. Instead, their visuals felt interactive, with real photographs and videos from their work mirroring their discussion.

Public speaking is hard. Speaking about your own high-level research to a mixed group is even harder. I was amazed at both speakers' grace and clarity and so appreciated their generosity in sharing their work with the larger campus community.

— Rafi Lehmann, Class of 2020

Luis Gerra, a graduate student in chemistry, gives one of the day's 10-minute talks — of which there were 103 — titled “Investigating Nonequilibrium Systems with Diffusion Integrated Nanoscale Temperature-Shift Spectroscopy.”

Session: “Slice of Princeton II”

Sometimes research proposals emerge when you’re least expecting them. Senior Sophia Alvarez was home with her family in New Orleans over the summer when sections of the city unexpectedly flooded.

“I was doing ethnography in New Orleans for a month, and I happened to arrive three days after a very substantial flood,” she explained. From then on, she decided to write her thesis as an ethnography of New Orleans’ flood infrastructure. She found that the breakdown of infrastructure leads to elective action by the city’s residents and hopes to use her research to spur further political action to address the city’s crumbling flood infrastructure.

The poster summarizing this research was one of dozens your social sciences correspondent observed during the session "Slice of Princeton II." Other researchers used more unorthodox methods to explore their topics.

Nora Benedict, a postdoctoral researcher, used network mapping methods through the Center for Digital Humanities to explore the connections between Victoria Ocampo, a 20th-century Argentinian writer and her contemporaries. This application of modern research methods to humanities studies allowed her to glean greater insights into Ocampo’s influence on Argentinian literature.

“So much of what we focus on in Latin American literature is about men,” Benedict said, “but what we see here is a lot of literary production from women.”

The beauty of the project was that Benedict planned to code datasets for this research and then release them to other researchers to spur further analysis.

For this correspondent, Princeton Research Day offered key insights into how our peers conduct their research projects. Hopefully many other students were also able to enjoy the plethora of projects at this year’s PRD — and then draw from those projects for their own research.

— Nicholas Wu, Class of 2018

The Princeton Research Day awards ceremony Thursday afternoon brought together presenters, judges, volunteers and audience members to celebrate Princeton’s commitment to research and the day’s best presentations.