At Princeton Research Day, senior Julia Peiperl explains her research and costume design for a production of "Charles Francis Chan, Jr.'s Exotic Oriental Murder Mystery," which served as the basis for her presentation poster, as judge David Redman listens in. The second annual event featured more than 140 presentations by undergraduates, graduate students, postdoctoral researchers and other campus researchers from engineering, social sciences, natural sciences, humanities and the arts.

From Aristotle explained through the lens of a soccer match to a technique for measuring a human's heart rate by using a webcam, the second annual Princeton Research Day served up a day full of intriguing findings from across the University.

The Thursday, May 11, event on campus featured more than 140 presentations by undergraduates, graduate students, postdoctoral researchers and other campus researchers from engineering, social sciences, natural sciences, humanities and the arts. Even a few high school students who work with campus researchers participated.

President Christopher L. Eisgruber, speaking at the day-ending awards presentation, said Princeton Research Day highlights a key aspect of the University's mission.

"Research is obviously one of the things that distinguishes us in our mission," Eisgruber said. "We aspire to contribute to the world through the research we do, the discoveries we make and the ideas we're able to get out to the world. But it's also an indispensable element of the teaching we do here."

(For more on student research, see "Zebras, peppers and philosophy: PEI Discovery Day showcases diversity of student research in environmental studies.")

Philip Gleissner, a graduate student in Slavic languages, presents his 10-minute talk on "Soviet Journals Reconnected: Periodicals and Their Networks under Late Socialism."

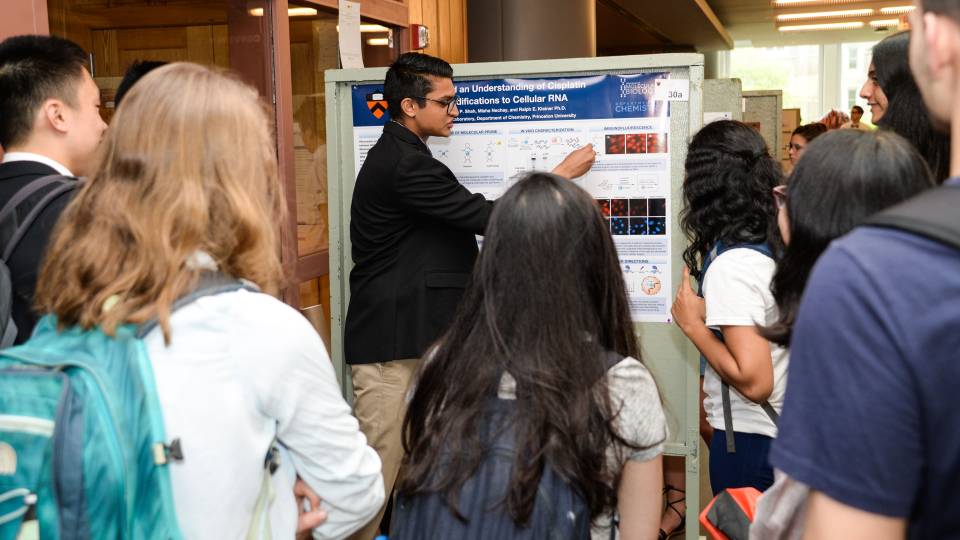

The event drew hundreds of students, faculty members and staff, who explored poster presentations throughout the first floor of Frist Campus Center and filled rooms for talks that reached across disciplines.

"This is a wonderful way of inviting the campus community and the community beyond campus to come and take a look at the very exciting range of research activities we have at Princeton," said Pablo G. Debenedetti, dean for research and the Class of 1950 Professor in Engineering and Applied Science and professor of chemical and biological engineering.

The event was a collaborative initiative among the offices of the dean of the college, dean of the faculty, dean of the Graduate School and dean for research, with support from the Office of the Provost.

Senior Angela Kim, who is majoring in molecular biology, discusses her poster, titled "Roles of RpoS and Efflux Pumps in Strengthening the Permeability Barrier of Stationary Phase Escherichia Coli Cells," with judge Yaakov Weinstein.

Valerie Wilson, a member of the Class of 2018 majoring in history, gave a 10-minute talk on her research on "plague searchers," poor women employed to search dead bodies for signs of the plague in 17th-century London. The event offered her the opportunity to share her work with a new audience and to take a fresh look at it herself, she said.

"Presenting today really made me think about the wider context of what I'm doing in a way that research, or even presenting to other people studying history, doesn't always lend itself to," Wilson said.

Her session, titled "In and Around the Clinic," also featured presentations by a graduate student in chemical and biological engineering on what happens when cells don't divide, an undergraduate in neuroscience on efforts to increase the inclusion of women in random controlled trials, and a postdoctoral researcher on new approaches to fighting multidrug-resistant bacteria.

"I really liked the diversity of the presentations," Wilson said.

Melanie Weber, a first-year graduate student in applied and computational mathematics, said she hoped Princeton Research Day would help her connect with others interested in her work on mathematical characterization of neural networks.

"It's a good opportunity to talk about my work and maybe connect with some of the great mathematicians and neuroscientists here to get them interested in the methods so they can be applied to new data," she said.

For Jonah Hyman, a member of the Class of 2020 who presented a theory on why big projects like New York City subway expansions always seem to run behind schedule, the event was a payoff for many lonely hours of research.

"After all the time you spend looking through records and watching (Metropolitan Transportation Authority) board meetings, it's nice to get your research out there," he said.

Writers for the Princeton Correspondents on Undergraduate Research blog fanned out across Princeton Research Day and offered their perspectives on the event:

Sophomore Debopriyo Biswas presents the poster he created with Yonghyun Song and Stanislav Shvartsman titled "dNTP Metabolism in Early Drosophila Melanogaster Embryos." Joining the conversation are Adam Maloof, associate professor of geosciences, and Amanda Irwin Wilkins, director of Princeton Writing Program.

Emma Kaeser, Class of 2018

Session: "Challenging the Status Quo"

This session, which consisted of four 10-minute presentations, featured researchers ranging from an undergraduate in geosciences to a graduate student in religion. Despite their diverse focuses, each presentation challenged pre-existing notions. I was struck by how the presentations' strategies for challenging the status quo resonated with each other and revealed common themes in research across disciplines.

In his presentation, "Physics in Exotic Number Systems," graduate student Sarthak Parikh discussed how we can develop a new language of numbers, or an "exotic number system," to understand particle forces that cannot be described using real numbers.

This theme of invoking a new language to understand something familiar in a new way surfaced in other presentations as well. Mary Nickel, a graduate student in religion, gave a presentation titled "Is It Not a Sharing? A Christian Politics of Koinona" in which she used certain Biblical language to reframe Christian politics of individualism. Nickel used this specific language to explain how the community, rather than the individual, is the unit of condemnation and redemption.

I was struck by how the theme of language connected these two presentations from quite distinct disciplines. Both Parikh and Nickel challenged the status quo in their fields by applying a new vocabulary that enabled them and the PRD audience to re-envision concepts we thought we fully understood. To me, this connection reinforced the notion that language is the lens through which we comprehend what we study. In research, altering that language can serve as a tool for digging deeper into our assumptions and discovering something novel and remarkable.

Senior Jennifer Lee, who won a Gold Award for her poster on "Using Optogenetics to Investigate How Cells Make Decisions," poses with Dean of the Faculty Deborah Prentice, who presented the award.

Vidushi Sharma, Class of 2017

Session: "Elevator Pitch I"

This was an incredible and quick way to get a taste of my peers' research in different disciplines, including history, philosophy, population studies and engineering. The first presenter talked about the Schleswig-Holstein War, the second (me) talked about argument mapping as a tool for reducing people's political biases, and the third, a philosophy student and Princeton soccer coach, talked about Aristotle's conception of the good life. Finally, we heard from a graduate student in population studies about immigrant fertility rates and another graduate student working on engineering microbes to produce chemicals.

Usually, learning about someone else's research takes a huge time commitment in the form of either a long conversation, presentation or paper — but this was a wonderful way to expose myself to many different kinds of research, with the ability to follow up later on the topics that I enjoyed the most. The event had a good mix of presenters and audience members including undergraduates, graduates, administrators and professors.

Witnessing different presentation styles was important and illuminating. Three presenters spoke with notes from short PowerPoints, one used a whiteboard to draw out his argument, and another simply stood on stage and talked. It was helpful to realize how different styles suit different topics depending on the importance of visual materials.

Zoe Sims, Class of 2017

Session: "New Ways of Knowing"

What do helical music, laser-generated X-radiation and bread mold have in common?

I attended "New Ways of Knowing" to find out. The presenters took us on a journey from medieval monasteries to 19th-century test tubes to modern particle accelerators. Along the way, they convinced me that their disciplines — music, physics and history — aren't as different as I had thought.

Our first presenter, visiting student research collaborator Rodrigo Batalha, spoke about the history and surprising mathematics of musical notes. A musical scale, represented spatially, makes a helix: starting with do…re…mi…and finishing back at do, this time an octave higher. The scale spirals upwards. At the presentation's conclusion, Batalha asked the audience to clap in rhythm. Joining the beat, he demonstrated how the same mathematical intervals used in the notes of a scale are also used in musical rhythms.

The second presenter, Matthew Edwards, a graduate student in mechanical and aerospace engineering, shifted the discussion from sound waves to light waves, and from the beats of music to the beats of attoseconds. At 18 orders of magnitude shorter than a second, attoseconds are the timescale associated at which electrons whiz around the nuclei of atoms. Attosecond-scale X-ray radiation, generated in huge, expensive particle accelerators, is very useful for studying molecular structures. Edwards explained how the same kind of radiation can be generated by shooting a laser into plasma, shrinking a kilometer-scale facility to a tabletop.

Junior Kyle Berlin gives his 10-minute talk titled "In Search of Eleanor Rigby, Or, The Sadness Project: Melancholy, Memory, and Ruin," which encouraged listeners to embrace their sadness.

Finally, Charles Kollmer, a graduate student in the history of science, took the stage to explain how scientists started studying microbes as models for all of life. When I was growing E. coli and prodding the tiny lab worm C. elegans in introductory biology, it never occurred to me to question the circumstances leading us to study such small, simple organisms as representative of big, complicated ones like humans. Kollmer's research shows this shift occurred mostly in the early 1900s, facilitated by a few seminal publications and a flood of new technologies including better microscopes and synthetic media for culturing bacteria.

Like microbes and men, these three research presentations appeared very different, but had their most fundamental elements in common. The session's title, "New Ways of Knowing," summarized one unifying theme. But I'd also propose several alternative titles. The session focused on scientific discovery: of ancient musicians, modern physics and the mid-1900s microbiologists. It covered the role of timing: in musical rhythm, particle acceleration and scientific change. And, of course, it was all about waves: of sound, light and innovation.

Presenters, judges and guests celebrate Princeton Research Day at a day-ending reception that included the presentation of awards.