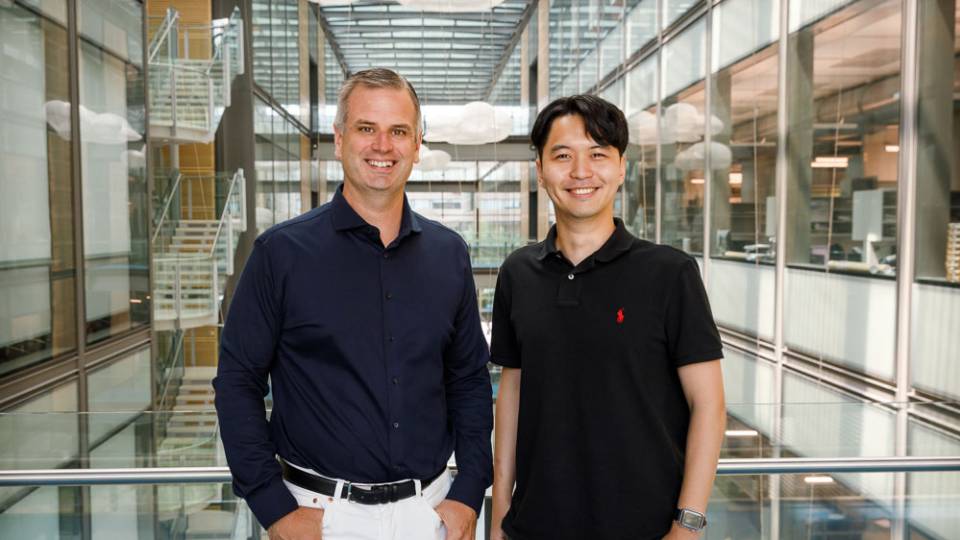

Emily Carter, the dean of engineering at Princeton, and John Mark Martirez, a postdoctoral researcher, have developed a method that could drastically reduce the energy needed to manufacturer synthetic fertilizer and other important industrial chemicals.

Nitrogen-based synthetic fertilizer forms the backbone of the world food supply, but its manufacture requires a tremendous amount of energy. Now, computer modeling at Princeton University points to a method that could drastically cut the energy needed by using sunlight in the manufacturing process.

Manufacturers currently make fertilizer, pharmaceuticals and other industrial chemicals by pulling nitrogen from the air and combining it with hydrogen. Nitrogen gas is plentiful, making up about 78 percent of air. But atmospheric nitrogen is hard to use because it is locked into pairs of atoms, called N2, and the bond between these two atoms is the second strongest in nature. Therefore, it takes a lot of energy to split up the N2 molecule and allow the nitrogen and hydrogen atoms to combine. Most manufacturers use the Haber-Bosch process, a century-old technique that exposes the N2 and hydrogen to an iron catalyst in a chamber heated to more than 400 degrees Celsius. The method uses so much energy that Science magazine recently reported that manufacturing fertilizer and similar compounds represents about 2 percent of the world’s energy use each year.

A research team led by Emily Carter, Princeton’s dean of engineering and the Gerhard R. Andlinger Professor in Energy and the Environment, wanted to know if it would be possible to use light to weaken the bond in the atmospheric nitrogen molecule. If so, it would allow manufacturers to cut radically the energy needed to split nitrogen for use in fertilizer and a wide array of other products.

“Harnessing the energy in sunlight to activate inert molecules such as nitrogen, and greenhouse gases methane and carbon dioxide for that matter, is a grand challenge for sustainable chemical production,” said Carter, who is a professor of mechanical and aerospace engineering and of applied and computational mathematics. “Replacing traditional energy-intensive high temperature, high-pressure chemical manufacturing with sunlight-driven, room-temperature processes is another way to decrease our dependence on fossil fuels.”

The researchers were interested in taking advantage of the unique behavior of light when it interacts with metallic nanostructures smaller than a single wavelength of light. Among other effects, the phenomenon, called surface plasmon resonance, can concentrate light and enhance electric fields. John Mark Martirez, a postdoctoral researcher and member of the Princeton research team, said that the researchers believed it would be possible to use plasmon resonances to boost a catalyst’s power to split nitrogen molecules.

“It is a different method of delivering energy to break the bond,” he said. “Instead of using heat, we are using light.”

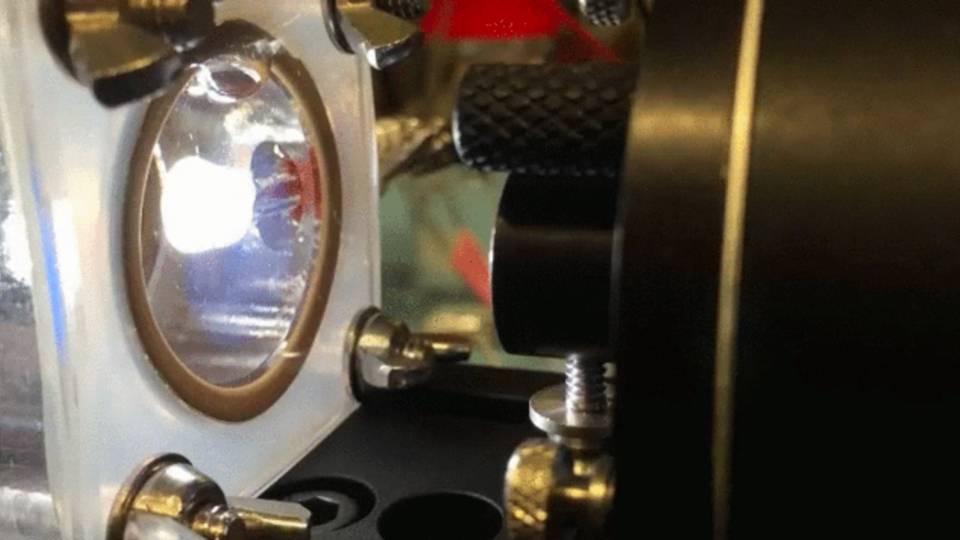

Nanostructures made from gold concentrate light and boost molybdenum’s ability to pull apart the two nitrogen atoms in an N2 molecule.

In a Jan. 5 article in the journal Science Advances, the researchers describe how they used computer simulations to model light’s behavior in tiny structures made from gold and molybdenum. Gold is one of a class of metals, including copper and aluminum, that can be shaped to produce surface plasmon resonances. The researchers used a set of computer modeling tools to simulate nanostructures made of gold, and added molybdenum — a metal that can split nitrogen molecules — to its surface.

“The plasmonic metal acts like a lightning rod,” Martirez said. “It concentrates a large amount of the light energy in a very small area.”

The concentrated light energy effectively boosts the molybdenum’s ability to pull apart the two nitrogen atoms.

“The interaction of light magnifies the electric field close to the surface of the catalyst, which helps break the bond,” Martirez said.

The researchers’ calculations indicate that the plasmon-resonance technique should be able to reduce substantially the energy needed to crack the atmospheric nitrogen molecules. Carter said the modeling indicates it should be possible to dissociate the nitrogen molecule at room temperature and at lower pressures the Haber-Bosch process requires.

Simulating the process while also considering the effect of light was challenging. Most computer models that can accurately assess chemical reactions at the molecular level, and account for changes induced by light, can only simulate a few atoms at a time. While this is scientifically valuable, it does not usually suffice for evaluating industrial processes.

So the researchers turned to a technique originally developed by Carter that allows scientists to use highly accurate methods for modeling a small fragment of the surface and then extend those results to get an understanding of a wider system. The technique, called embedded correlated wave function theory, has been repeatedly verified and extensively used within the Carter group, and the researchers are confident in its application to the nitrogen-splitting problem.

Carter said her team is collaborating with Naomi Hallas and Peter Nordlander of Rice University to test the plasmon-resonance technique in the lab. The researchers have worked together on similar projects in the past, including demonstrating the dissociation of hydrogen molecules on pure gold nanoparticles.

As a next step, Carter said she would like to extend the plasmon resonance technique to other strong chemical bonds. One candidate is the carbon-hydrogen bond in methane. Manufacturers use natural gas to supply the hydrogen in fertilizer as well as other important industrial chemicals. Finding a low-energy method to break that bond could also be a boon to manufacturing.

Support for the project was provided in part by the Air Force Office of Scientific Research, the High Performance Computing Modernization Program of the U.S. Department of Defense, and Princeton’s Terascale Infrastructure for Groundbreaking Research in Engineering and Science.