Sarah Rivett

Sarah Rivett, an associate professor of English and American studies at Princeton University, specializes in early American and transatlantic literature, religion and indigenous history.

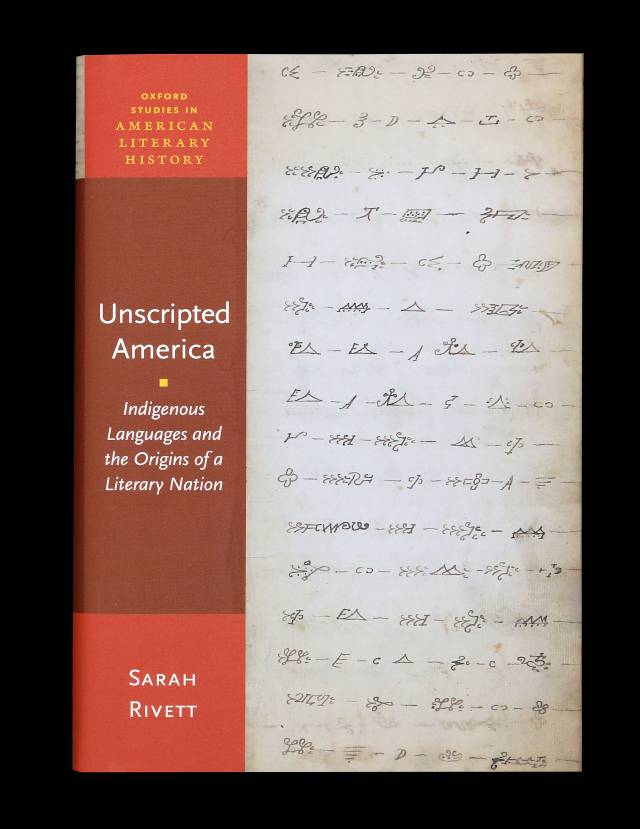

In November, Rivett's latest book, "Unscripted America: Indigenous Languages and the Origins of a Literary Nation," was published by Oxford University Press. "Unscripted America" explores the impact of colonial language encounters between indigenous and European populations on Enlightenment language philosophy and early American literary history.

Rivett's previous book is "The Science of the Soul in Colonial New England (Oxford University Press, 2011), which examines intersections between the scientific revolution and the rise of Protestantism in Anglo America. It was awarded the Brewer Prize of the American Society of Church History in 2013.

In 2016, Rivett and her colleague, Sophie Gee, an associate professor of English, won a $50,000 Innovation Grant for New Ideas in the Humanities through the Dean for Research Innovation Funds. Their project, "The Global Enlightenment," brought together leading scholars across disciplines at a conference to discuss the Enlightenment as a complex, global phenomenon that has had lasting impacts on religion, race, and geographic and cultural diversity.

How has your training and approach in literature, religion and history come to bear on this project?

I am attracted to research questions that cannot be answered within the limits of the discipline that I’ve been trained in, which is English. Part of the reason for this is that the field of early American literature requires us to read texts that wouldn’t be classified under the category of literature in the canonical sense.

My work on this book began with a fascination with a vast archive of American Indian language texts, consisting of vocabulary lists, grammars, translated catechisms, dictionaries and sermons, all written in indigenous languages by missionaries and Native American interpreters. The interpretive methods traditionally taught in an English department are insufficient for understanding these texts. I needed to know something about the ways that theology impacted the act of translation. I needed to know something about historical linguistics and about indigenous studies. My book tries to develop a cross-disciplinary model of interpretation, which is what I thought would be most useful in trying to understand colonial indigenous language encounters.

How are indigenous languages central to early American literary history, and why are they often forgotten?

Linguistic anthropologists have declared dead or dying most of the eastern Algonquian languages that I analyze in my book. Languages such as Massachusett, Narragansett, Unquachog and Mahican are believed to have disappeared sometime over the 19th century. Other languages such as Mi’kmaq have a few thousand speakers, while others such as Maliseet-Passamaquoddy have only a few hundred speakers. These languages are often forgotten because they are not believed to be living languages. However, language revitalization programs have taken off over the past two decades. In many cases such as Massachusett and Unquachog, tribal descendants have reconstructed their ancestral language from the colonial archive. So I’m not sure it’s the case that these languages are dead.

The claim that I make in my book is that these indigenous languages were not only spoken but also very present in the literary imaginary of the 18th and 19th centuries. Writers such as James Fenimore Cooper, Henry David Thoreau and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow were deeply influenced by indigenous languages. These authors mainly knew of these languages secondhand. For example, James Fenimore Cooper learned about Lenni Lenape from the Moravian missionary John Heckewelder. Nonetheless, ideas about Native American words had a profound impact on the style and form of early American writing.

How did colonial language encounters between indigenous and European populations transform early colonists’ understandings of language itself?

In the 17th century, Christian missionaries went to North America with clear ideas about the universality of biblical history. They largely believed that words were signs of divinely revealed truths. They also believed that the fall of the Tower of Babel dispersed human populations around the world and contributed to the great diversity of tongues. These Christian missionaries believed that by studying indigenous languages, they could recuperate an etymology of the biblical past.

As strange as this idea sounds to us today, missionaries were shocked to discover that this was not the case. Colonial linguistics forced missionaries to confront the reality of language as a human construct. By translating Christian texts into Mohawk, Mohican or Mi’kmaq, they came to understand that each language carried with it ideas of culture and of a distinct cosmos. So colonial language encounters actually led to more secular understandings of language even though this was opposite of what the missionaries intended.

‘Unscripted America’ is a close analysis of previously overlooked texts, including European scripture and literature and indigenous language texts. What were the challenges in analyzing these works, and what was the most surprising thing they revealed to you?

By far the biggest challenge was language. I wish that I spoke every indigenous language that I write about in my book.

Instead, I had to get by with dictionaries and learning what I could in a reasonable amount of time while still keeping the larger picture in mind. I think the reason that these texts are overlooked is because very few literary scholars know indigenous languages — though this is changing. So previous generations of scholars haven’t quite known what to do with these texts.

In "Unscripted America," I tried to sit with the discomfort of being a linguistic outsider in order to develop a formal, aesthetic and historical approach to the texts that did not require knowing 30 Algonquian and Iroquoian languages. There is something instructive about surveying a vast body of texts that are at least partially impenetrable, for it gives us insight into the resistant structures encoded in the languages themselves.

This project is more about the failures than the successes of translation. I suppose that this was the most surprising thing the texts revealed to me — by sitting with the limits of our own knowledge as scholars, we can glean valuable insights into historical processes that are themselves often attempts to overcome such limits.

What aspects of this period of U.S. history do your students find most eye-opening?

That depends on how well I teach. Early U.S. history is intrinsically eye-opening but in ways that are often not immediately apparent.

It’s hard to read a Puritan diary — or a sermon — and see relevance to the U.S. today. So navigating one’s way through this material requires a committed and enthusiastic guide.

What I love about early American literature is that it can seem incredibly historically distant at first but that historical distance illuminates aspects of our contemporary culture that we may otherwise miss.

Two genres, the captivity narrative and the jeremiad, were invented in 17th-century New England. Once one studies them, their form can be spotted across a range of news stories and political speeches. When my students see this dynamic—the way that what appears historically distant can be not only interesting but also relevant, colonial American literature becomes eye-opening.