John McPhee

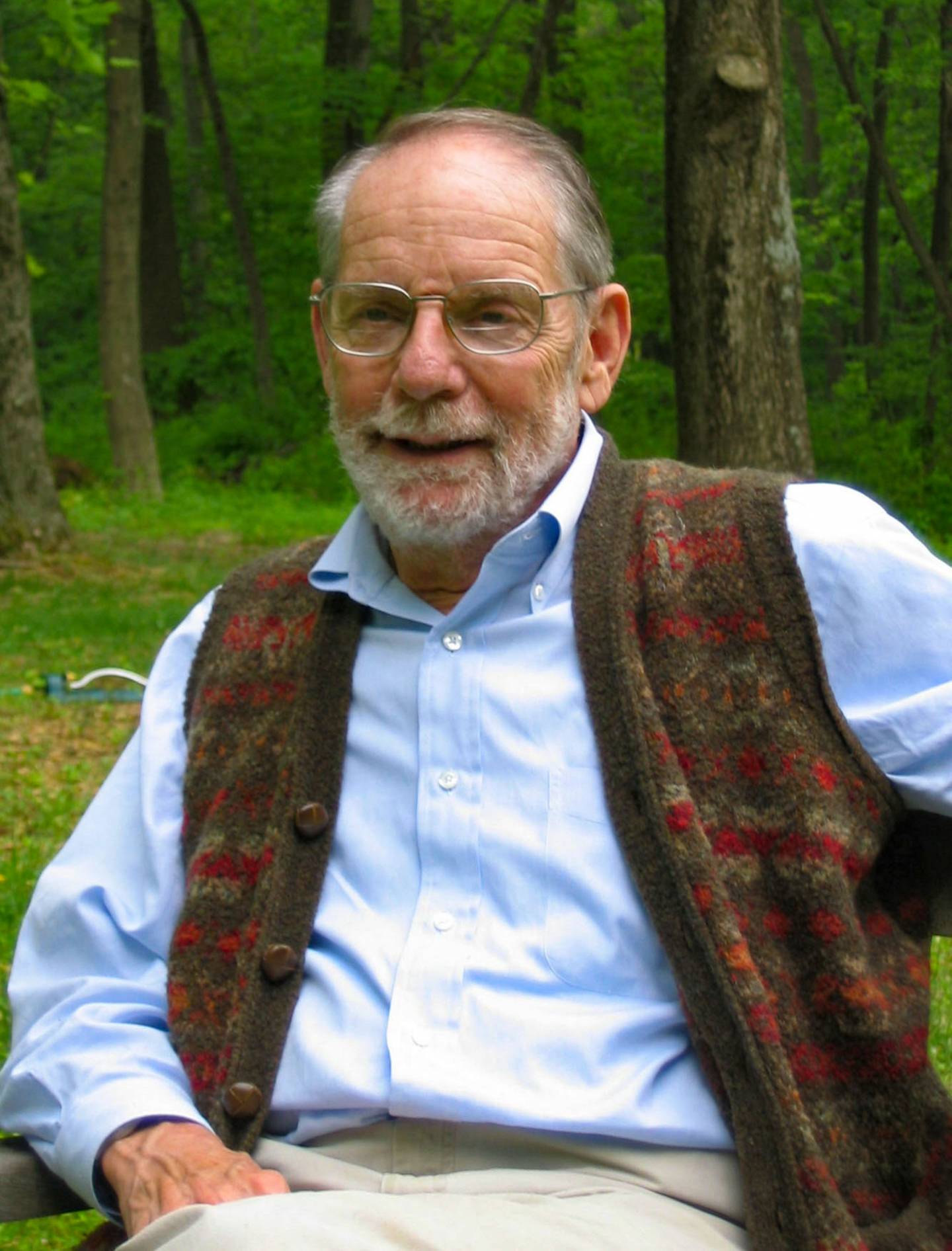

From his office in the fifth floor tower of Guyot Hall, home of the Department of Geosciences, John McPhee can look down through two vertical windows and see the office in McCosh Health Center where his father served as a medical doctor for Princeton University Athletics from 1928 until the late 1960s. McPhee, a Ferris Professor of Journalism in Residence, was born and raised in Princeton and attended elementary school at 185 Nassau St., now the home of Princeton's Program in Visual Arts. A 1953 alumnus, he has taught writing at Princeton since 1975: his course, "Creative Nonfiction" (originally called "Literature of Fact"), offered each spring, is open to Princeton sophomores, by application, and limited to 16 students. To date, nearly 450 students have taken the course.

In 1999, the same year he received the Pulitzer Prize for his book "Annals of the Former World," McPhee received the President's Award for Distinguished Teaching from Princeton. He has been a staff writer for The New Yorker for over 50 years, where much of the content of his 32 books originally appeared. His new book on writing, "Draft No. 4," was released Sept. 5 (Farrar, Straus and Giroux). At 6 p.m. Tuesday, Oct. 24, McPhee and two former students, authors Joel Achenbach and Robert Wright, will appear in conversation at Labyrinth Books, 122 Nassau St.

These musings are from a June 27 interview.

In fourth or fifth grade, I would go to [Princeton] football practice every day and hang around the players. On Saturdays when they played, I ran into the stadium with them and I had a shirt with orange and black stripes on it and the number 33. One November day, it was bitter cold with a rain that came down at a 45-degree angle and wind. It was miserable down there on the sidelines. I looked up at the press box and I realized that those people up there were in heated space and they were under a roof and they were earning their living just by tapping out words. Then and there, I decided to be a writer.

A very high percentage of my work derives from things I got interested in at the camp I went to in Vermont, where my father worked in the summers. I have described it as "a classroom of the woods." You had to learn a whole hell of a lot of trees, at least 25 species of trees. I could rattle off the names of the trees, and the names of ferns and rocks. There were 150 canoes, and we went on many canoe trips; that's what I loved more than anything else. And backpacking trips. All that relates to a lot of my later interests and ultimately my books.

"Draft No. 4," McPhee's 32nd book, was published Sept. 5 by Farrar, Straus, Giroux.

A fundamental thing that I picked up from Mrs. McKee, my high school English teacher, was her demand that you turn in with every piece of writing some kind of structural outline. Could be anything: Roman numerals, doodles, it didn't matter, but something that the writer had done beforehand in order to plan and shape the material. That has been a requirement in all the 43 years that I've taught the [Princeton] course. That came straight from her. I get some really elaborate drawings from Princeton students.

I was rejected by The New Yorker for 15 years. I really worried a lot when I was in my 20s about being a writer and what kind of a writer. The first professional writing I did was live plays for television. You try different things. I was trying to get hired by The New Yorker and they wouldn't have me.

A New Yorker "staff writer" is an unsalaried freelancer and has to think up subjects. So where do they [the subjects] come from? Certain accidents can happen. After a vacation with my daughters, I go to the home of a Deerfield roommate in Rhode Island and I'm playing doubles against this tennis club's so-called pro and a man named Mason Willrich, a total stranger. Afterward, Mason says he is a law professor, and he asks me what I do. I tell him I'm a writer of nonfiction pieces in The New Yorker. This wakes Mason up and he starts talking to me about the possibility of clandestine theft of special nuclear material from private industry — that is to say, what terrorists could do with the nuclear material. They could make a bomb. He is doing a study of the problem for the Ford Foundation. So he plants that idea in my head. And that's out of nowhere. I'm a professional writer and I'm looking for things to write about. I write about real people in real places. So I got into that subject and it took, almost on the nose, a year.

As an interviewer, I don't think I come on very strongly, and I think that's an advantage. I'm shy, and I get into people's worlds and I don't know anything. I think that in my sort of work a person who perhaps had more confidence might end up with less material, if you see what I'm saying. I mean, if you obviously need help, who's going to help you but the person you're trying to write about?

"There are many things I learned from John — the value of a roadmap as you sit down to write your story, so you have some sense of the arc of the journey, is probably the most valuable. But I learned so many more things just by observing how he conducted himself, asking more questions than talking, how meticulously he prepared for class and the notion that all the torture involved in getting it right was worth it."

— Jim Kelly, Class of 1976. Contributing editor at Vanity Fair; former editor of Time magazine; New York City

Time is the thing that has always favored me. My pieces take a long time and I'm around the subject a lot. Then they get used to me and we're kind of working on it together. And that's the nature of it. I'm awestruck by the skill of daily journalists who go out and come back and get this whole thing done in a day.

You're always looking for framework for your story. Sometimes, it just presents itself. A good example is the ending of "Looking for a Ship," which is about the decline of the U.S. Merchant Marine. A merchant ship loses its power in the Gulf of Panama, goes dead in the water and is creaking back and forth, and up the halyards run two big black balls, just great balloon-like things, jet black — "Not under command" is what that means. We've lost all power. And we're wallowing and creaking in the swells, and right there you think, this is where the book should end. So I had to work out how to end with a flashback, which is a totally legitimate thing to do.

"After a spring of seminars with John, I returned to spend the summer in the small town of Gilmanton, New Hampshire — as I had done for 14 years. This time, it was different. I spent afternoons listening to a 100-year-old neighbor, feeding calves with sixth-generation farmers, learning the art of raking wild blueberries, and scouring the town's 33 graveyards to find a man who was buried twice (once with each of his wives). It led to my first book, 'Driving Backwards' (2014). John made me see the extraordinary in the ordinary."

— Jessica Lander, Class of 2010. ELL/social studies teacher, Lowell (Massachusetts) High School; contributing writer, Boston Globe, Harvard Education Magazine, Huffington Post, Princeton Alumni Weekly

When I teach in the spring semester, I let the writer lie fallow. I've never written anything during the spring semester. Then I go back to writing with fresh vigor and I'm writing through summer, fall and January. I have no way to prove this but I think I've written and published more, over the years, than I would have had I not spent those semesters teaching. Teaching and writing have been symbiotic for me.

People will say to me at some party, it's really impossible to teach writing, isn't it? The analogy I would use is I'm like a swimming coach. The swimmers can swim really well, but the coach is watching them and showing them how to be a little more efficient and how to develop that stroke to shave some seconds off.

The real core of the [creative nonfiction] course is the weekly private conferences. It takes me all of Saturday and Sunday to prepare. The students come here one at a time, and we go through each paper a comma at a time. I do a combination of what an editor does and what a copy editor does. I go through their papers with a fine-toothed comb and fill up the margins with comments.

I'm amazed by the students. There are no deadbeats. The reason that all this stays the same from year to year is because the students differ and because their choices of subjects differ.

I very much want to try to relax young writers — as much as is possible — about how things go in their 20s. I'm hoping young people will fret less if I help them fret less, which is not necessarily going to work.

"John's tiniest edits have stayed with me for 40 years. I once wrote that victorious Frisbee teams drank from the disk, chugging ‘48 ounces of beer or champagne, a choice governed by the class of the challenger vanquished.’ John suggested, How about 48 ounces of beer or ‘48 ounces of champagne’? Since then, I have dwelled on the cadence of every sentence I composed. Following Princeton, my own ‘Literature of Fact’ has consisted of 500 scientific papers in molecular biology, including the sequencing of the human genome. John has shaped every one and doubled its impact."

— Eric Lander, Class of 1978. President and founding director, the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, Cambridge, Massachusetts

Editor's note: Eric Lander and his daughter, Jessica Lander, are among three parent/child "alumni" of McPhee's course: The others are Alex Gansa, a member of the Class of 1984, and Will Gansa, a 2017 alumnus; and Bart Gellman, two-time Pulitzer Prize winner and a member of the Class of 1982, and Lily Gellman, a 2017 alumna.

A central component of writing is the faculty of knowing why something isn't good, of being aware of what's wrong. How else would you be able to fix it if you didn't know that there was something not working? You'd just leave it.

A deep belief of mine is that writers are unique. It's like the idea of a thumbprint or a snowflake — or, I learned the other day, a whale's fluke. They're all different. You are you, and you consist of countless components. In your writing, all of that is going to produce something nobody else is ever going to write in that way. So, a writer develops herself. These are mantras of mine.

In the first assignment of the semester, I pair them by the alphabet and send them off to interview each other and do a profile of the other student. The next assignment is a set piece, described as a certain component of a longer piece of writing. For example, you're narrating a journey in canoes through the north Maine woods and you pause to describe a loon. The loon is a symbol of the north Maine woods, so you spill out everything you know about loons and then get back to the main thing. The students imagine books they are writing and do set pieces for the books on any subject of their choice. The next assignment is to describe some building or other structure on this campus so that a reader who has never been to this campus could get an idea of what the building is and what it looks like.

The last third of the course is total free choice on their part. They don't have to leave Princeton, that's the one thing I tell them, to do a perfectly good piece, but they do. And they've done very interesting things over the years. Like kite fighting in India. [One student] was on a trip to Paris for another course and she went to a shop her father had been an apprentice in long ago to learn to make the bows of stringed instruments — there's a name for it, like a farrier makes horseshoes, and a fletcher makes arrows. I'm slipping on the term. Another student got in touch with the company that runs ferries back and forth between Lewes, Delaware, and Cape May, New Jersey, 17 miles across the mouth of Delaware Bay. He rode the ferry back and forth, he arranged to do it, arranged with the Humanities Council to help him get down there.

"John would read our sentences aloud slowly so that we could hear that they were hackneyed. It was never embarrassing, though. If I fought for a phrase, he listened with curiosity. 'Tell me your concept of paragraphs,' he wrote in the margin of an essay once. I'm weak at structure, which is an important part of John's class. By calling me an intuitive writer, he gave me the confidence to work harder at structure."

— Lilith Wood, Class of 2000. Research coordinator, Baird Financial Advisors, Seattle

In weekly one-on-one conferences with his students, McPhee goes over each essay "with a fine-toothed comb," scribbling his notes in the margin. Many of his students save their marked-up essays forever. This comment — "horses with wakes behind them? Both images are excellent -- They cancel each other, though" — is from an essay by Lilith Wood, a 2000 alumna and native of Alaska who asked her mother to unearth her essays from the family's attic for this story.

This is a perfect example of a nugget that a nonfiction writer runs into: One day, after my seminar ended in Joseph Henry House, out comes a student — same one who rode the Lewes ferry — with a fishing rod in his hand. He's going down to Carnegie Lake to try to get material for a story. He doesn't fish. He's a reporter with a prop. He goes along the towpath, encountering fishermen and interviewing them. And who does he find there but a guy — a voluble, interesting, quotable guy — who was once a prizefighter and fought George Foreman in the ring and sparred with Muhammad Ali!

I ride my bicycle every other day, about 15 miles. There's lots of great places to ride around here.

The danger in the thesaurus lies in someone wanting to pluck up some fancy word; that's not what it's all about. The essential thing is a dictionary with a very good synonym component. Some dictionaries will explain the difference between each synonym and the others it lists, which I think is fascinating. Webster's Collegiate is very good. I look up far more words that I know than ones that I don't know.

I'm a faculty fellow of men's lacrosse. Here's what we do: We're around. We're not there to advise, let alone coach. We're just there to be part of the team in any way that we want to. I go to practices as often as I can and we travel with the team. I really like it. Bill Tierney, the [former head] coach, asked me if I'd do it and I had no idea what it was about. I've been doing that for at least a dozen years. I described it in The New Yorker as voodoo.

"For years after I graduated, I used to feel John sitting on my shoulder like Jiminy Cricket, whispering 'excess verbiage' or 'move the comma' into my ear. He took you seriously. John always supported my crazy decision to move to Calcutta, where I grew up, because he said it was important to have the widest possible set of experiences at a young age, as that would fuel the writing."

— Kushanava Choudhury, Class of 2000. Author of "Epic City: The World on the Streets of Calcutta" (2017), based on his experiences working as a newspaper reporter; currently working on a book in Cochin, India

Nabokov is a precursive rapper. He'll go: "I went into the room and ruminated." He'll have line rhymes that go on and on, and alliterations that go on and on, and alliterative line rhymes out the door. He's verbally intoxicated. Pat Moran, who teaches in the Writing Program, was singing the praises of Jeremy Irons reading Nabokov's "Lolita." I had never finished the book so I thought it would be interesting to hear Irons doing this. Right now in my car, that's what's going on.

I fret about any piece of writing I get into, because nothing you do in the past is going to do the next thing, even when you're in your 80s. I would never sit down and think I was about to turn out something good. Quite the opposite.

I learn a lot of interesting stuff reading students' papers, what they've researched, what they're looking into. I really like doing this — or I wouldn't be here. As long as I can, dealing with these sophomores is an extremely healthy thing to be doing.