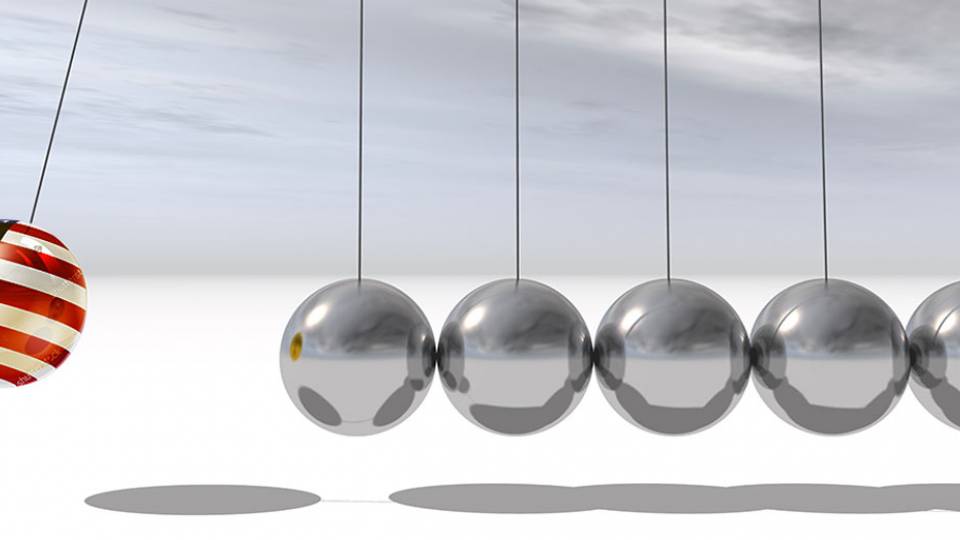

The term "populist" has been used to describe a wide range of politicians around the world in recent years, from Hugo Chávez to Nigel Farage to Donald Trump.

But what does the term actually mean, and who is a populist?

Jan-Werner Müller, a professor of politics at Princeton, explores those questions and their significance in his new book, "What Is Populism?" (University of Pennsylvania Press).

Müller, a Princeton faculty member since 2005, specializes in democratic theory and the history of modern political thought. His other books include "A Dangerous Mind: Carl Schmitt in Postwar European Thought"; "Another Country: German Intellectuals, Unification and National Identity"; "Constitutional Patriotism"; and "Contesting Democracy: Political Ideas in Twentieth-Century Europe."

He has also addressed issues related to populism in recent pieces in The Guardian, The Financial Times, the French weekly L'Express and the German weekly Der Spiegel.

Müller answered questions about populism, his book and its relevance to the 2016 presidential campaign.

"What Is Populism?" is politics professor Jan-Werner Müller's latest book. (Book cover image courtesy of the University of Pennsylvania Press)

Question. Why did you tackle this question, "What is populism?"

Answer. I wanted to confront two issues in particular. First, populists — especially, but not only, in Europe — often present themselves as the real champions of democracy. I wanted to know whether that self-presentation was at all valid. Second, I was disturbed by commentators' lazy — I'd even say unthinking — way of suggesting some kind of symmetry between, for instance, Bernie Sanders and Donald Trump (or, in the European context, left-wing parties such as Podemos in Spain and Syriza in Greece on the one hand, and right-wing populists such as Marine Le Pen [France] and Viktor Orbán [Hungary] on the other). I sought to understand if all these actors really have something in common.

Q. What is the biggest misconception about populism?

A. Today, we read in virtually every second op-ed piece that the world is witnessing a growing alienation between elites and the people, or that across the West there is a "revolt of the masses" against the establishment. However, not everyone who criticizes elites is a populist (in fact, any standard civic-education book will positively encourage us to be critical citizens). Rather, populists always claim that there is a homogeneous, morally pure people of which they are the only authentic representatives. For them, it follows that all other contenders for power are corrupt or in some other way immoral. Less obviously, they hold that whoever does not support them among citizens does not properly belong to the "real people." Think of Nigel Farage celebrating the Brexit vote by claiming that it had been a "victory for real people" (thus making the 48 percent of the British electorate who had opposed taking the U.K. out of the European Union somehow less than real — or, rather, questioning their status as members of the political community). Figures like Sanders or Britain's Jeremy Corbyn criticize elites, of course, but they are not anti-pluralist in the way Le Pen, Farage and Trump are. And only the latter are a danger for liberal democracy.

Q. What can we learn from recent populists, such as Silvio Berlusconi in Italy and Hugo Chávez in Venezuela?

A. Many observers think that populists offer very simplistic policy prescriptions which will quickly be exposed as unworkable. Conventional wisdom also has it that populist parties are primarily protest parties and that protest cannot govern, since, logically, one cannot protest against oneself. In fact, though, populists can govern specifically as populists, in line with their claim to a moral monopoly of representing the real people. This explains why populists with sufficient majorities and weak countervailing institutions — such as Orbán in Hungary, Erdoğan in Turkey, or, indeed Chávez in Venezuela — have taken their countries in an authoritarian direction. Berlusconi was dangerous, but he was much more constrained by the existing political and legal system than these other figures; he also had no large ideological project to reshape society in line with a conception of the "real people"; and, not least, he always had to worry about his own troubles with the law.

Q. How can claims that populists speak exclusively for "the silent majority" be countered?

A. In a diverse democracy containing many interests and identities, populists' anti-pluralism opens the path to excluding entire groups — and to authoritarianism. Those fighting populists have to be absolutely explicit about this danger and should not shy away from calling a racist a racist, in a case like Trump's. But they also have to avoid a trap: they end up contradicting themselves if they, in turn, demonize the supporters of the demonizers, or effectively end up saying: "because you exclude, we exclude you." It's the trap that Hillary Clinton fell in when she criticized Trump voters as "deplorables." Above all, liberal democrats have to offer both substantive policy ideas that can work for voters of populist parties and conceptions of a pluralist collective identity that are more attractive than the populists' fantasies of pure peoplehood.

Q. How does Donald Trump fit in this picture of populism?

A. Trump has said so many horrendous things over the course of the past year and a half that one remark at a rally in May passed virtually unnoticed — even though that statement clearly showed the populism at the heart of Trump's worldview: "The only important thing," he said, "is the unification of the people — because the other people don't mean anything." Like all populists, Trump engages in a certain form of exclusionary identity politics (which is not to say that all identity politics has to be populistic): he decrees who belongs to the real American people and who doesn't. What is unusual is the openness with which he has incited hatred against minorities in this process.

It is also worth saying that Trump, contrary to what some academic observers have claimed, is not an "elitist," just because he himself is so obviously part of a certain elite. It's naive to assume that one has scored a decisive point against populists by pointing out that they themselves are not exactly commoners. Populists promise not that they themselves are authentically "ordinary," but that, contrary to the corrupt elites, they will faithfully implement the real will of the real people.

Q. How does this book fit in the broader scope of your work?

A. As political theorists, we should engage with actual political challenges; that engagement can at the same time help in rethinking long-standing theoretical puzzles. Confronting populism has pushed me further in addressing hard questions about the relationship between ideals of self-government and the institutional machinery of political representation, as well as the difficult issue of where the boundaries of "the people" should be drawn.