Tension mounted at the Lewis Center for the Arts' Lucas Gallery as Julia Wilcots, a civil and environmental engineering major at Princeton, hung small sandbags from the graceful wood bridge that spanned the gallery's clean white walls.

The bridge — thin strips of ash crossed in an X and mounted at their four ends — bowed and shimmied with each new weight. Its stresses and deflections seemed to transmit directly into the intently watching students gathered for the final session of "Extraordinary Processes," a seminar offered jointly by the Program in Visual Arts and the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering.

Having succeeded in meeting the course requirement of loading the bridge with 16 pounds, Wilcots and fellow student Neeta Patel tried radically shifting all the weight to one end, and Wilcots could not bring herself to fully release her hand from the last weight as the asymmetrical structure danced near the edge of its stability.

"Go for it," said Patel, a senior majoring in Program 2 studio arts in the Department of Art and Archaeology and Wilcots' partner in making the bridge.

"I love it," said Joe Scanlan, director of the Program in Visual Arts who co-taught the class this fall. "The artist is saying 'Let go!'"

It was the sort of moment that Scanlan and his collaborator Sigrid Adriaenssens, assistant professor of civil and environmental engineering, had hoped for as they invented a course to nudge students beyond their comfort zones at the boundary of art and engineering. The two began talking a couple years ago about teaching a class together and looked for a theme that appealed to both of them and was not grounded specifically in either art or engineering.

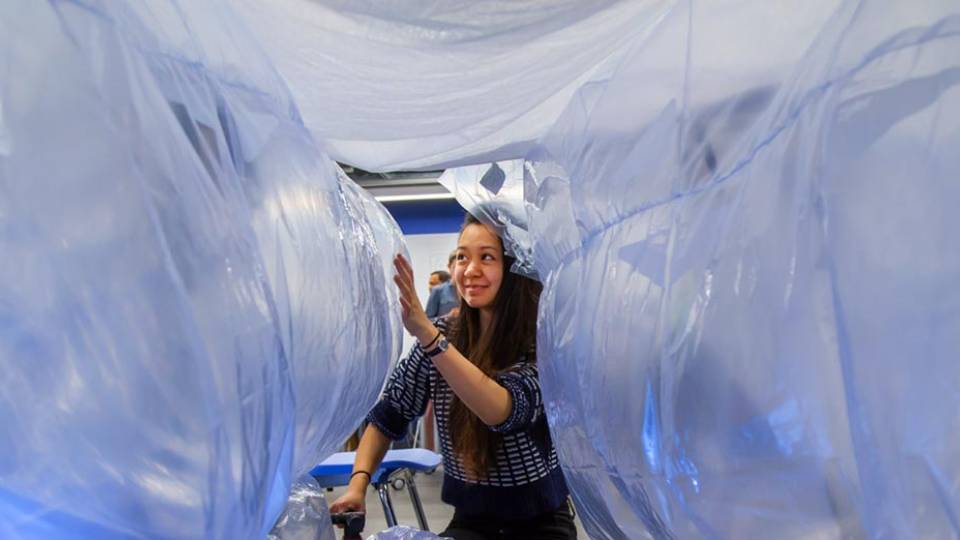

Neeta Patel, an art and archaeology major (left), and Julia Wilcots, a civil and environmental engineering major (right), hang weights from their bridge in the Lucas Gallery of the Lewis Center for the Arts as their classmates look on. The constructions will be on view in the gallery through Tuesday, Feb. 9.

An environmental crisis provided the impetus they needed: the recent decimation of ash trees by an invasive insect, the emerald ash borer. First discovered in Michigan in 2002, the insect's destruction of ash trees has spread across the Eastern United States, reaching New Jersey in 2014. With tens of millions of trees lost, ash lumber is temporarily plentiful. As Scanlan and Adriaenssens researched ash and its plight, the more intrigued they became.

"It wasn't any old tree," Scanlan said. "It was the wood that made the 20th-century leisure culture — tennis racquets, picnic baskets, canoe paddles. It has a lot of interesting structural properties — you can work with it really thin as a veneer, you can work with heavy pieces, and it's very amenable to steam-bending."

During the semester, the students heard talks by experts engaged in the ash tree crisis and visited the studios of legendary woodworker George Nakashima in New Hope, Pennsylvania. They built their own apparatus to steam-bend wood, a process of exposing wood to high-temperature steam until it becomes pliable, and conducted lab sessions that explored the difference between mathematical predictions and actual experience. They made self-portraits out of ash and culminated the semester with the bridge project.

During the semester, the students mastered a variety of woodworking techniques, including cutting thin strips and using steam to soften and bend pieces of wood. As a final project, the students built bridges that were required to support 16 pounds and also to deform and spring back when the weights were added and removed.

The title "Extraordinary Processes" came from the idea that "extreme amounts of invested time and manual labor are capable of transforming the ordinary into the extraordinary," according to the course description.

"To work with one material so intensively for one semester is really enriching," Adriaenssens said. Immersed in cutting, carving, bending, weaving, buckling and simply handling the ash wood, the students' creativity grew.

"Their bridges show systems that I haven't really seen before," Adriaenssens said. "They were really playing with it."

At first, the two professors noted that the students' approaches to the class were firmly rooted in their respective disciplines. "Arts students bristled at the measuring and utility that was woven into the class," Scanlan said. "Engineers were dubious about discussions of aesthetics."

As the semester progressed, however, arts students developed forceful ideas about utility and engineers were appreciating the aesthetic success that is possible even in something that failed a structural test.

"In the end there was not so much a split — here is an engineer and here is an artist," Adriaenssens said. "The boundaries softened and the two had really merged."

The course was taught by Joe Scanlan, professor of visual arts (left), and Sigrid Adriaenssens, assistant professor of civil and environmental engineering (center with white notebook). At right, senior Michelle Chang, a civil and environmental engineering major, ties candies to her team's bridge to test its strength.

One group made a looping chain of veneer-thin strips bent into figure eights and fastened with a combination of rivets and embroidery thread. Their first challenge had been making the strips. "The more we did it, the better we got at making a consistent thickness," said Veronica Nicholson, a senior majoring in Program 2 studio arts in art and archaeology, as she hung fruits to weight the bridge during the class demonstration.

"Then we were surprised by how strong and versatile the loops were," said her teammate Lu Lu, a senior majoring in civil and environmental engineering.

With the strips in hand, the group did not make detailed drawings or calculations beforehand like those in traditional bridge design. "The process was very tactile," Lu said. "It was respecting and exploring specific properties and potentials of the material, instead of focusing on a drawing which might hinder that process."

Michael Cox, a junior majoring in civil and environmental engineering, said it was the first class he's had that not only focused almost entirely on hands-on problem solving but also incorporated an aesthetic viewpoint. "It is really interesting having both Joe and Sigrid's perspectives," he said.

He built a bridge with seniors Olivia Adechi, who is concentrating in Spanish and Portuguese languages and cultures, and Lauren Frost, who is concentrating in Program 1 history of art in the Department of Art and Archaeology. The team wanted their bridge to compress horizontally like an accordion when loaded. Adriaenssens helped them think about a system of hinges and a pulley-like arrangement of strings that pulled their structure sideways. But Scanlan suggested turning the whole plane of the mechanism from vertical to horizontal.

"It was a suggestion that would only come from the two perspectives combined," Cox said.

In the end, their bridge consisted of two arms, each made of four hinged segments, that crossed the gallery in a large horizontal polygon. The weights pulled segments closer, while others moved apart. "It was spectacular how it moved," Adriaenssens said.

From left, sophomore Katie Kennedy, Patel, Adriaenssens and Wilcots watch as a bridge is loaded.