Hugo Meyer, a professor of art and archaeology emeritus at Princeton University whose scholarship focused on Greek sources of Roman art and Hellenistic and Roman sculpture, died from an accident at his home in Munich on Sept. 12. He was 66.

Meyer joined the Princeton faculty in 1988 and was promoted to professor in 1992. He retired in 2012.

"Hugo's many years in the department, and at Princeton, will be long remembered by many," said Michael Koortbojian, the M. Taylor Pyne Professor of Art and Archaeology and chair of the department.

According to a department statement on the occasion of his retirement, Meyer was an extensive traveler throughout Europe and the Middle East and was known among colleagues to have fluent conversations in an astonishing number of what he liked to call "European dialects" — and could recite major works of poetry in Celtic.

Meyer earned his Ph.D. in Classical art and archaeology from the University of Göttingen in 1978 and his "habilitation" in 1986 at Ludwig Maximilians-Universität Munich (LMU). He spent the first decade of his academic career in Germany, teaching at the Institut für Klassische Archäologie at LMU, as a visiting professor at Marburg University and taking on a curatorial position responsible for a collection of plaster casts of Classical sculptures at the Bavarian National Museum in Munich.

When he joined the Princeton faculty, Meyer worked to rebuild the art and archaeology department's cast collection with William Childs, professor of art and archaeology emeritus. The rebuilt collection became a teaching tool made up of numerous examples of Classical sculpture housed in various European museums, many of which were borrowed from the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. While the department promotes worldwide travel for undergraduate and graduate students to see the originals, the cast collection, now housed on McCormick Hall's third floor, is still in use for precepts.

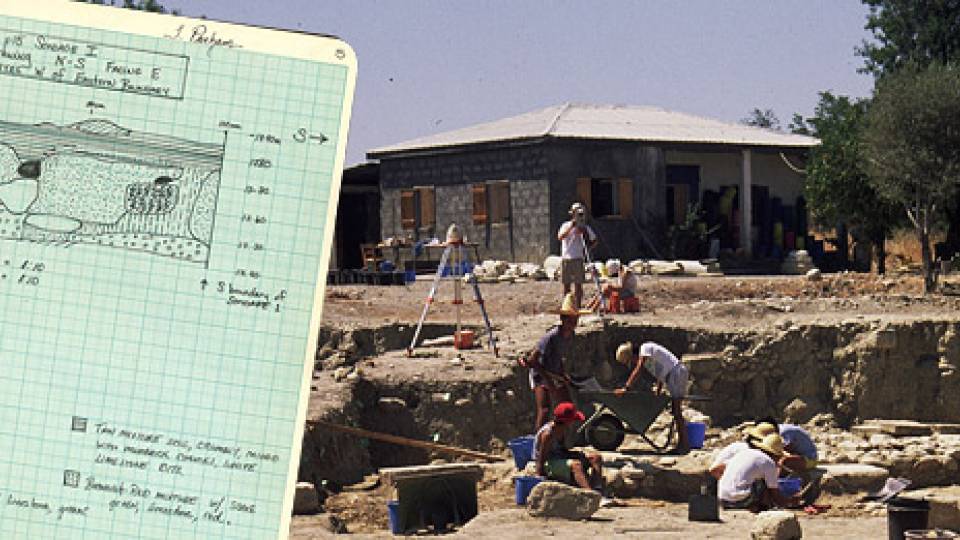

"His scholarly work ranged over many areas of Greek and Roman art, but his particular interest was in Roman portraiture, a field in which he made important and lasting contributions," said Childs, who remained close colleagues with Meyer throughout their time at Princeton. In 1998 and 2000, Meyer joined Childs at the excavation of Marion-Polis in Cyprus, which Childs oversaw for three decades.

Childs also noted the many ways Meyer's expertise supported broader academic efforts at the University. "Hugo read everything not only in his main field of Roman art, but Greek art, [and] European art and retained everything he read," he said. "He carried this diligence over into vetting candidates for the Graduate School and especially faculty appointments in all fields. Given his broad interests he had many devoted undergraduates; graduate students found him a strict task-master."

While at Princeton, the two courses Meyer taught most frequently were "Roman Art" and "Roman Cities and Countryside: Republic to Empire." He also taught "Magic in Ancient Art and Literature," "From Golden Age to Crumbling Border: The Antonine Era," "Roman Painting," "Problems in Roman Art," and "Art History, Basic Aspects and Recurrent Concepts," among others.

"It was sad, but on the same day that news reached us of Hugo's untimely death, the mail brought a copy of a new book by Margaret Laird [an advisee of Meyer's who earned her doctorate in 2002], whose acknowledgments page begins with her recollection of 'Hugo's infectious love of Roman art' and its impact on her," Koortbojian said.

Laird, an adjunct associate professor of Latin and classics at the University of Delaware, said she came to Princeton intending to study Greek art and archaeology, but Meyer convinced her to "relocate" to Rome.

"His delight in his subject bubbled over, his curiosity was unlimited and his enthusiasm was infectious," Laird said. "He also had the finest eye for style and iconography I have ever encountered and a near-encyclopedic ability to recall practically every sculpture he had seen. One autumn, when I returned to Princeton, Professor Meyer took one look at my (very) short haircut and immediately exclaimed, with a laugh, 'Aha! Pompey the Great!,' comparing my locks to those of a first century B.C.E. general."

Meyer's interests extended to folk music, ethnology, geography and other topics, striking a chord in students and colleagues.

"He was gifted with an eye for detail I have rarely seen," said Zehavi Husser, an associate professor and chair of the art department at Biola University in La Mirada, California, who earned her doctorate from Princeton in classical archaeology in 2008 with Meyer as her adviser.

Husser said Meyer had an indelible impact on her scholarship and her own teaching. "I learned from Hugo how to approach Roman art and how to evaluate it critically," she said. "Perhaps, most importantly, he taught me always to be open to new ideas. He certainly was. He empowered his students to be the professionals he was training them to be. Consequently, in my own teaching, I have tried to emulate him in this way."

Heather Russo, a 2004 alumna pursuing a doctorate at Princeton with a focus on Roman art and archaeology, first studied the subject with Meyer as an undergraduate. "For him, the ancient world was very much alive and tangible. He reminded his students that looking — truly looking — at objects was a skill to be practiced and developed in just the same way that one practices translating ancient texts," she said.

While Meyer was born in Lüneburg, northern Germany, he spent most of his life in Bavaria. According to Russo, Meyer wore a traditional Bavarian wool jacket in winter — often to visit the newsstand in Palmer Square in downtown Princeton to pick up international publications to keep up his reading skills. "On more than one occasion, casting agents approached him on the street and asked him to be photographed as Santa Claus," said Russo. "He himself acknowledged that he looked the part, but Hugo Meyer was humble when it came to recognizing that he embodied and exuded the accompanying qualities: generosity, kindness of spirit, thoughtfulness and a perpetual twinkle in his eye."

Edward Champlin, the Cotsen Professor of Humanities, also noted that "constant twinkle in his eye" as well as Meyer's keen observation skills as a scholar and teacher — revealed in particular during a graduate seminar on the "Age of Augustus" he co-taught with Meyer several years ago.

"His erudition was massive and his critical standards fierce, and my fondest memory of all comes from one of our seminars on a grey Friday afternoon," Champlin said. "I offered some timid observations on an artwork in one of his slides. He made no comment but as we walked over for a drink afterwards, he dissected what I had said and concluded, 'You have a good eye.' I've been absurdly proud of that remark ever since."

In the 1990s, Meyer embarked on a comprehensive history of imperial Roman art and published two books on sculptural works, the first on the figure of Antinous — Emperor Hadrian's lover and the subject of Meyer's habilitation — and the second, contributions to a catalogue of Roman sculpture in the Princeton University Art Museum. The latter led to the exhibition "A Seleucid Prince in Egypt," which Meyer curated for the State Museum of Egyptian Art in Munich, along with an exhibition catalogue. He also published dozens of essays in books of collected works, journal articles and reviews, and lectured widely.

He continued his scholarship from Munich upon retirement with research trips and travel to sites, museums and landscapes of the Mediterranean world. His interests remained wide and varied; he published on German folk tales and was writing a book on Albert Einstein.

He is survived by his wife, Michaela Fuchs; his daughter, Sibylle Meyer; and her husband, Gabriel Matt.

Donations may be sent in Meyer's memory to the Institut für Klassische Archäologie at LMU by emailing Claudia Herkommer at herkommer@lmu.de.