Princeton economist Harrison Hong has spent much of his career working to understand how and why asset-price bubbles form. Hong, the John H. Scully '66 Professor in Finance, has studied the dot-com bubble in stock prices from 1997 to 2000 and the run-up in global commodity prices from 2003 to 2008.

His latest insights, though, come from the check-out line at your local grocery store.

Hong and colleagues from University College London and New York University dug into data on the shopping habits of more than 100,000 U.S. households and pricing information from 20,000 grocery and retail stores to learn more about the 2008 Rice Crisis — a brief but dramatic episode that saw rice prices soar worldwide.

Their findings offer a clearer picture of how individual households react when prices jump and could help guide government efforts to stabilize markets when there are fears of food shortages, said Hong, who is affiliated with the Bendheim Center for Finance at Princeton.

Hong and co-authors Àureo de Paula of University College London and Vishal Singh of New York University discuss their research in a working paper titled "Hoard Behavior and Commodity Bubbles," which was released in March through the National Bureau of Economic Research.

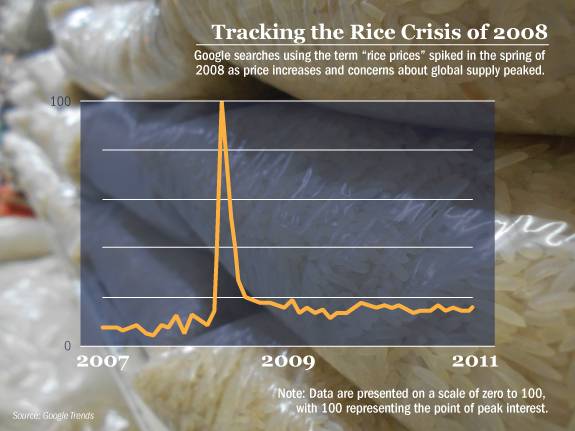

The crisis began when India moved to prohibit rice exports in late 2007, setting off a domino effect among other major rice exporters and sparking fears of shortages in nations that must import the basic foodstuff, including the Philippines. There were no significant shortages in the United States, Hong said, but prices spiked for several months.

Such episodes often spark concerns that large speculators are driving up prices by hoarding scarce supplies, Hong said. But the researchers found that in the United States, individual households were the ones hoarding rice — including households that purchased rice for the first and last time at the height of the panic.

"Each person wasn't hoarding that much — perhaps an extra couple of months' supply — but in aggregate it adds up to a lot," Hong said.

As prices increased in the United States, rising as much as 50 percent a week in April and May 2008, shoppers stepped up their purchases out of fear the price increases would continue, Hong said.

"When consumers see big price run-ups in a short amount of time — whether it's in the price of food, stocks or homes — that catches consumers' attention," Hong said. "You can call it survival instincts. You can call it speculative behavior. But people respond."

In a few places, the extra purchases emptied shelves of big retailers like Wal-Mart and Costco, prompting the stores to limit purchases. The sight of empty shelves and word of purchase limits — combined with the media coverage that followed — likely fed into the fears of buyers, Hong said.

Just as quickly as it began, though, the panic eased and prices fell in June 2008 after an agreement allowed Japan to sell some of its rice supply internationally. The same U.S. households that stepped up their purchases as prices jumped stopped buying rice as prices fell, using up their stored stocks, Hong said.

The information gleaned from the reaction of U.S. shoppers could have broader implications, Hong said.

"In a place like the Philippines where households have fewer resources and are more dependent on rice, you can imagine that hoarding behavior would be even more significant," Hong said. "Our findings suggest that one way to stabilize markets would be to basically promise households a certain ration of rice, which would reduce the fear of households about being able to obtain the food they need."

While the Rice Crisis of 2008 wasn't much of a crisis in the United States, Hong said it presented an unusual opportunity to study consumer behavior in the face of a price bubble.

"People have wanted to study hoarding for a long time, but it's difficult to simultaneously have an event that was big enough to study and also have available this very, very detailed data available that allow you to really trace every aspect of household and consumer behavior," he said.