Yes, there are reasons to worry about the Chinese housing market. But they may not be the reasons you expect.

That's the message from researchers at Princeton University, the University of Pennsylvania and Peking University who have built housing-price indices covering 120 major Chinese cities from 2003 to 2013 and analyzed detailed information on mortgage borrowers.

The good news: the enormous rise in Chinese housing prices has largely been accompanied by equally impressive income growth, and high down-payment requirements help keep leverage under control in the housing market.

The concern: borrowers at the low end of the market are enduring severe financial burdens to purchase homes at a cost of eight or more times their annual income. While that strategy can pay off if prices and incomes continue to rise, it also creates a risk if the nation's economy suddenly slows, said Wei Xiong, one of the researchers.

"They're stretching to buy now because they think their income will continue to grow and pressure will be lower later. And if prices continue to rise, of course it is better to buy now. The risk is how sustainable these kinds of expectations are," said Xiong, the Hugh Leander and Mary Trumbull Adams Professor for the Study of Investment and Financial Markets and a professor of economics at Princeton.

So while the Chinese housing market is unlikely to cause a big slowdown in the nation's economy, it could amplify such a slowdown as falling prices affect borrowers, builders and local governments, said Xiong, who is affiliated with Princeton's Bendheim Center for Finance.

The research is detailed in a working paper titled "Demystifying the Chinese Housing Boom" recently circulated by the National Bureau of Economic Research. The other authors are Hanming Fang of the University of Pennsylvania and Quanlin Gu and Li-An Zhou of Peking University.

Here are five charts from the research that help explain the Chinese housing market:

Before they could address concerns about the Chinese housing market, Xiong said the researchers first had to know how much prices have risen. Anecdotal evidence has suggested much larger price increases than official measures, he said.

The researchers used mortgage data from a major Chinese commercial bank to build new home-price indices, which measure prices by sequential sales of similar units in housing developments.

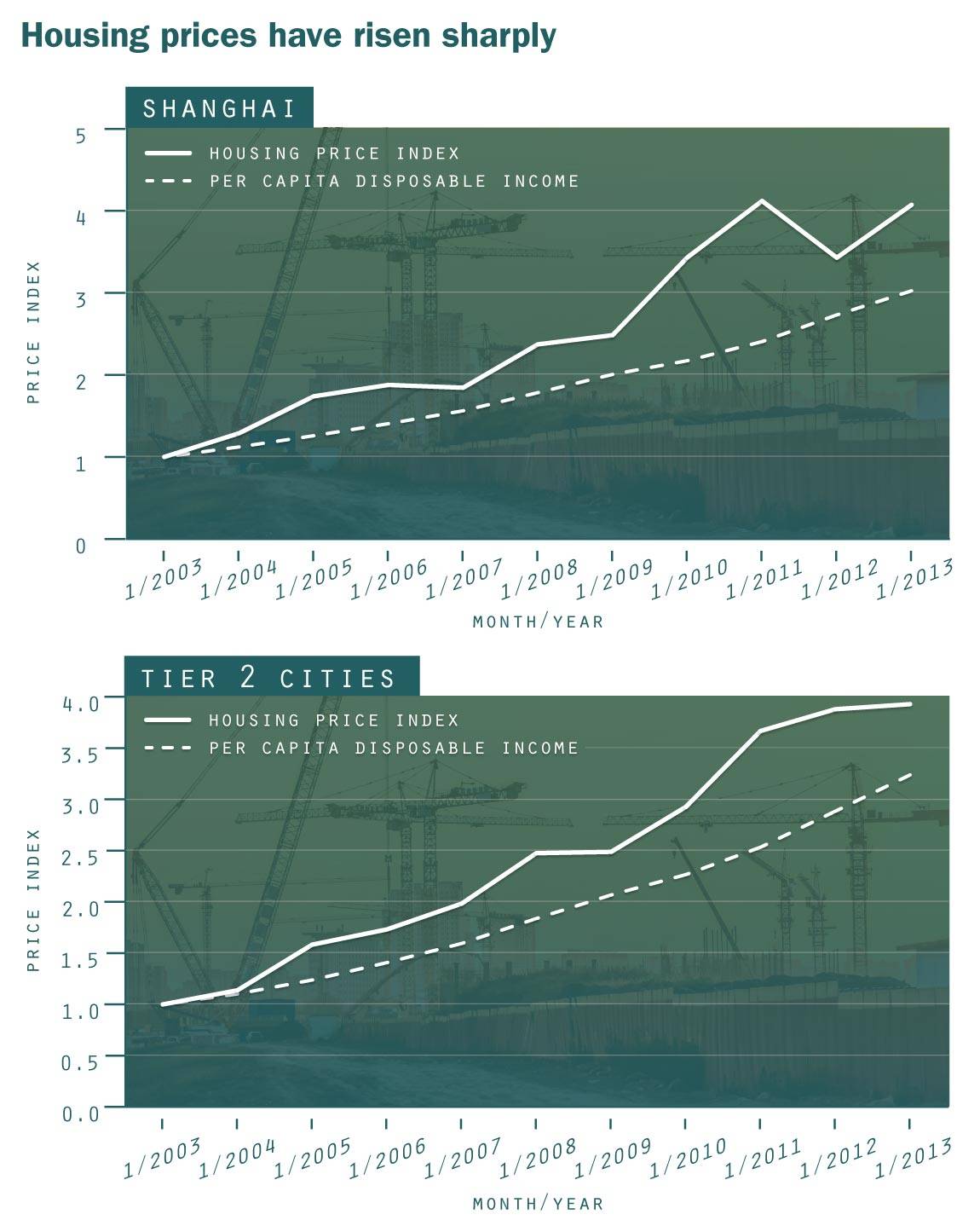

From 2003 to 2013, the indices show prices rose by an average of 13.1 percent annually (after adjusting for inflation) in China's four first-tier cities — Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou and Shenzhen. In smaller but still significant second- and third-tier cities, prices rose 10.5 percent and 7.9 percent annually, respectively.

Meanwhile, income increases largely mirrored the rise in housing prices.

"This housing price appreciation may be large compared with the usual standard, but if you benchmark it with income growth, they are more or less similar," Xiong said.

Chinese banks generally require down payments of more than 35 percent for middle-income borrowers and more than 40 percent for borrowers with the lowest incomes. That makes a debt-fueled housing crisis like the one experienced by the United States beginning in 2007 unlikely, Xiong said.

"Leverage isn't a big concern," Xiong said. "Even if housing prices drop by 30 percent, these borrowers are still above water and household default isn't a particular concern. That's reassuring."

Lower-income Chinese borrowers generally paid more than eight times their annual income for a home. (For comparison, a frequently cited guideline for U.S. home buyers is three times annual income.)

"Even after the big down payment, they still have a huge mortgage," Xiong said. "They have to pay the interest on the mortgage as well as pay down the mortgage, so they're consuming about half their income every month. That's a huge burden."

The researchers think those buyers are willing to struggle with the heavy mortgage burden because they expect incomes and housing prices to continue to rise.

"It's not our intention to say whether this will or will not persist," Xiong said. "But the risk is there. If the economy slows down, especially if there is a sudden stop, the housing market is going to crash."

Xiong says any drop in housing prices would affect more than homeowners. Real-estate developers are often heavily leveraged in China, Xiong said, exposing them to substantial risk if the housing sector slows. Also at risk, he said, are local governments. Local governments, which have a monopoly on land sales in China, often depend on such sales for more than half of their fiscal budgets. In smaller cities, the percentage can be above 90.

"Really these cities live on selling land," Xiong said. "So if housing prices crash, land prices will crash and all these local governments will be in trouble. The household sector seems to be the relatively safer part, followed by real estate companies and local governments."