Global headlines about Iran and nuclear weapons abound, but for her thesis one Princeton University senior is tackling an aspect of the country that is rarely discussed.

“There’s so much focus on Iran’s nuclear program, but there are other amazing things going on in the country that people don’t even know about,” said Miranda Kalvaria of New York City, a Near Eastern studies(Link is external) major.

Kalvaria’s thesis examines the impact of sex reassignment surgery and assisted reproductive technologies on various social groups in Iran.

In the mid-1980s, Iran legalized sex reassignment surgeries. In 2003, Iran legalized assisted reproductive technologies, including various types of in vitro fertilization and third-party egg donations. The country has a high infertility rate, particularly among males, and the second-highest rate of sex change surgeries in the world, after Thailand, Kalvaria said. In addition to making these technologies available to its own citizens, Iran has also become a destination for medical tourism, in particular for people from other Middle Eastern countries seeking these surgeries and procedures.

“I was intrigued by that, and I felt that most people would definitely not know that and would be very surprised,” she said.

Kalvaria’s original thesis idea focused only on the impact of sex reassignment surgeries. Her adviser Mirjam Künkler(Link is external), an assistant professor of Near Eastern studies whose research interests are in the politics of law and religion in Iran and Indonesia, suggested Kalvaria also look at assistive reproductive technologies, as she had never seen scholarship that examined these technologies together.

“I am focusing on how different groups — including lawmakers, religious leaders, doctors and affected constituencies — use the sex reassignment surgery and assisted reproductive technologies in contradictory ways that produce both intended and unintended negative and positive outcomes,” Kalvaria said.

“Miranda brings out the nuance to these complex issues, highlighting both the opportunities that come with the availability of these medical technologies as well as discussing their risks — both the health and social risks,” said Künkler.

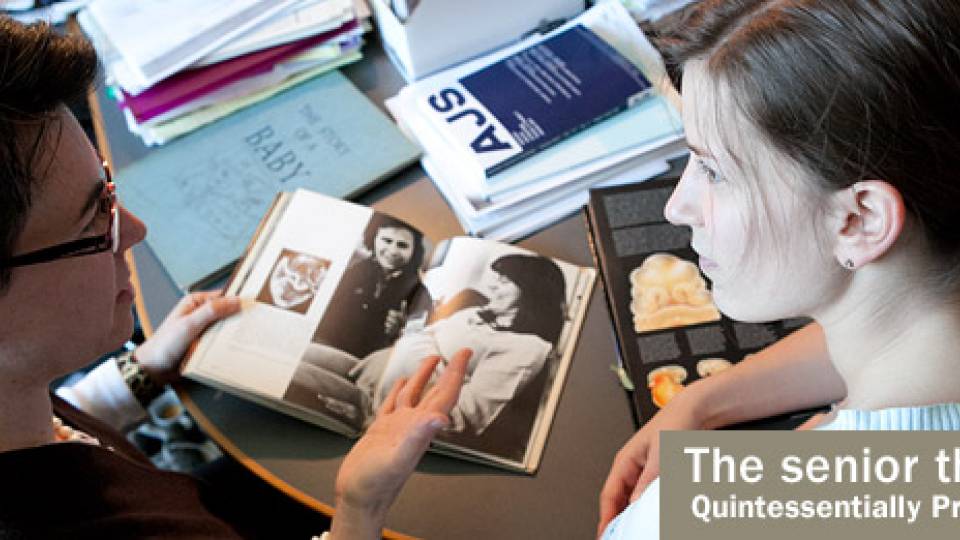

Kalvaria (right) credits her close working relationship with her adviser Mirjam Künkler (left), an assistant professor of Near Eastern studies, for helping to build her confidence to “do justice” to the emotional topic of her thesis. “She’s so reassuring,” Kalvaria said. “I don’t think any Princeton student has written about this topic, so I think she’s as excited about it as I am.”

While the technologies are legal and promoted by the government, the people who use them keep it a secret, Kalvaria said. For example, she learned that infertility is stigmatized in Iran, a largely Shiite country. “Having children is one’s ‘divine gift’ in Iranian culture. For those who can’t have children, assisted reproductive technologies have been called ‘marriage saviors’ — but the people who use them don’t want anyone to know that these children, for example, from third-party egg donors, are not their real biological children,” she said.

During her research, Kalvaria combed newspaper articles and scholarship and found that conclusions about how these issues reflect Iran’s culture fell into different camps.

Regarding sex reassignment surgeries, “one camp says the legalization of these technologies shows that Iran is progressive with respect to gender and sexuality issues,” she said. “The other says it’s a ploy of the government exerting social control over the population, even going so far as to pressure homosexuals to change their sex so that they’re in heterosexual relationships.”

While researching scholarship on fertility treatments, Kalvaria also found two groups, “those that believe the government legalized assisted reproductive technologies to help infertile couples have children and keep couples together and the other camp — related to the first — which focuses on how the government legalized the treatments to promote pronatalism [pro-birth],” she said.

In addition to making sex reassignment surgery and assisted reproductive technologies available to its own citizens, Iran has also become a destination for medical tourism, in particular for people from other Middle Eastern countries. (Illustration by the Office of Communications)

Kalvaria also reviewed human rights documentation and activists’ reports, and watched documentaries such as “Be Like Others” (2008), which was filmed in Iranian clinics that offer sex change surgeries and includes interviews with women and men before and after their surgeries.

She conducted interviews with several LGBT activists from Iran, now exiled for their sexual identities in Turkey and Canada. She also spoke with a legal analyst from the Iranian Human Rights Documentation Center in New Haven, Conn.

She said one of the greatest challenges she’s faced while writing the thesis has been the emotional nature of the topic. She is both passionate about raising awareness of the topic and concerned that her thesis will adequately present the many different outcomes — positive and negative — these technologies have on people’s lives.

“To not do the topic justice would be so upsetting to me,” Kalvaria said.

She said that Künkler’s support has built her confidence. “She’s so reassuring. She’ll email me out of the blue: ‘You’re doing great!’ She sends me sources all the time. I don’t think any Princeton student has written about this topic, so I think she’s as excited about it as I am.”

Kalvaria said she was drawn to the Near Eastern studies department because of its small size. “Everyone in the department is so close and involved,” she said. “I’ve spoken to about four different professors about my thesis, and anytime I can walk into their office.”

Kalvaria calls the thesis experience “a beautiful end to your four years of college — to have this book that you’ve written all on your own. What Princeton has taught me most is about writing,” she said.

After graduation, Kalvaria plans to become an investment banking analyst and is also considering law school.