In exploring the racial underside of political communications, Princeton University politics professor Tali Mendelberg has found that unspoken words can be the most damaging.

Mendelberg is a political psychologist who studies the ways in which individuals' thoughts, emotions and behavior affect political processes. Her research focuses on communication about race in political campaigns -- particularly the varying effects of implicit and explicit racial messaging -- and the role of race, gender and other factors in citizen deliberation.

Trying to understand why some groups of people harm or exploit others, and how to prevent this, is the impetus for Mendelberg's work. By studying inequitable treatment, she hopes to gain insights into the possibilities for political inclusiveness and fairness.

"Inequality is often unjust and harmful, so finding ways to understand and ultimately reduce it is a way to improve the lives of many people," said Mendelberg, an associate professor of politics who joined the Princeton faculty in 1994. Though inequality may be seen by some as benign, natural or inevitable, she said, "in politics, inequality is rarely any of those things."

Nolan McCarty, the Susan Dod Brown Professor of Politics and Public Affairs at Princeton, said Mendelberg is a "member of a very strong group of political behavior scholars" at the University. Among that group, she is the "most focused on the application of psychological theories and methods to problems in American politics," he said.

In addition, Mendelberg has been a "committed citizen" of the politics department who has worked hard to enhance the diversity of the faculty and graduate program, McCarty said, and she is popular as a teacher and mentor among graduate students "for her high level of engagement with their work."

Class participation is required in Mendelberg's "Racial Politics in the United States" course, as is respect for all views. Nelson Chiwara (right) of the class of 2011 contributes his thoughts to a discussion about the civil rights movement.

At Princeton, Mendelberg has taught courses in race and American politics, political psychology, deliberation and cultural conflict, race and democratic discussion, and public opinion.

Mendelberg's research is grounded in the social sciences -- she majored in psychology at the University of Wisconsin and received her Ph.D. in political science from the University of Michigan.

"When I started studying American politics and political psychology in graduate school, I became interested in the political psychology of racism. Race is one of the primary lines of demarcation in American society," Mendelberg said. "I wanted to understand how race is used to stigmatize socially, exploit economically and subordinate politically. Studying the ways that people think and feel about race is a way for me to understand the broader problem of racial subordination."

Mapping the race card's impact

Mendelberg's 2001 book, "The Race Card: Campaign Strategy, Implicit Messages and the Norm of Equality," documents the unspoken ways that race plays out in political campaigns. Mendelberg examines issues -- such as crime and welfare dependency -- that white voters have associated with minorities, and how those issues are raised (often with accompanying photos or video) to send coded messages to voters. Mendelberg concludes that "racial stereotypes, fears and resentments shape our decisions most when they are least discussed," because most people believe in fair treatment for all races and reject explicitly racist appeals but may be swayed subconsciously by subtle, coded references to longstanding stereotypes.

One example featured in the book is the 1988 presidential campaign and Republican candidate George H.W. Bush's focus on Willie Horton, a convicted murderer in Massachusetts, where Bush's rival Michael Dukakis was governor. Horton, a black man, brutally assaulted a white couple in their home while on a weekend pass from prison. Beginning in June 1988, the Bush campaign used the incident to charge that Dukakis was soft on criminals, and though race was not mentioned, a stereotype of black criminality existed in popular culture. Mendelberg notes that the Bush campaign knew Horton's race, and evidence suggests the campaign intended to send an implicit racial message to voters. Television ads and the news media often showed Horton's mug shot but neither the campaign nor the media made explicit mention of Horton's race for months, as Bush moved ahead of Dukakis in the polls.

In late October, civil rights activist Jesse Jackson, who had been a Democratic presidential candidate in that election cycle, charged the Republicans with using a racial appeal. The media then echoed that message every time the issue was raised, and Bush's ratings began a steep decline, though he won the election. Mendelberg analyzed survey data and supplemented the analysis with experiments to show that the message evoked racial stereotypes rather than nonracial considerations such as ideological conservatism; these experiments also demonstrated that the message loses its power when it is explicit.

"The Race Card" won the American Political Science Association's Woodrow Wilson Foundation Award for the year's best book on government, politics or international affairs. Princeton's Martin Gilens, an associate professor of politics, called it a seminal book on race in American politics that combines "historical, sociological and psychological approaches in analyzing when and why racial appeals in political campaigns succeed or fail."

The research has been "validated and extended by numerous scholars over the past decade," he said, noting that Mendelberg's work is characterized by methodological rigor, high-quality data and careful analysis.

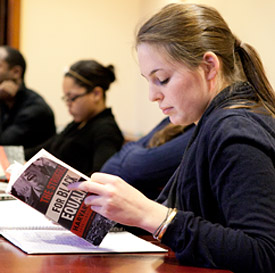

Rising senior Emily Myerson refers to the text "The Struggle for Black Equality" during a class discussion in Mendelberg's racial politics course.

Mendelberg has continued to study the role of race and racial messages in political campaigns. In a 2010 paper co-written by researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, University of Michigan and Princeton, Mendelberg and her colleagues found that sex scandals had a larger impact on black candidates than white candidates, both in terms of harming the candidates' overall favorability ratings and influencing perceptions of their ideology.

The research also broadened the study of implicit and explicit associations with race, which previously had focused on how white candidates used racial messages in their campaigns against other white candidates. The study found that implicit racial messages were more harmful to a black candidate than explicit racial statements.

In the study, participants were shown fake news stories about allegations of infidelity by two candidates for the 2008 Democratic presidential primary, John Edwards and Barack Obama, and they were asked to rate their approval for the candidates. Participants also were asked to rate the level of the candidate's degree of liberalism, to test the hypothesis that white voters' racial predispositions would lead them to form politically damaging perceptions of black candidates as more ideological, especially because black candidates are stereotyped as more liberal than the average white male. The study was conducted before Edwards actually was involved in an infidelity scandal after dropping out of the 2008 presidential race.

In the Obama scenario, the narrative about infidelity was itself an implicit racial cue because of a stereotype among whites that blacks are sexually promiscuous. Both the explicit and implicit appeals used the false news stories that included a photo of Obama flanked by two white women as another implicit racial cue.

For the version of the experiment testing the effect of explicit racial messages regarding Obama, the fake news story identified the woman in the scandal as "Sally Smith, a white woman," and included a quote from a political consultant about "situations in which black candidates engage in sexual indiscretions with young women." (Participants were briefed after the experiment and were told the stories were false.)

Though both Obama and Edwards were nearly evenly matched at the start of the experiment, researchers found that Obama was seen as liberal by more participants after the experiment with implicit messages, and also less favorably overall.

Initially 48 percent of white respondents said that Edwards was liberal and 44 percent said that of Obama; after seeing the news story, 64 percent of white respondents said that Edwards was liberal (a 16 percent increase), and 71 percent said Obama was liberal (a 27 percent increase). In terms of overall feelings about the candidates, on a scale of 100, Obama fared worse than Edwards among politically interested white respondents who read the version with implicit racial connotations, suffering a seven-point drop as opposed to Edwards' one-point drop. However, Obama's overall approval ratings were basically unaffected by the overtly racialized version of the story.

The researchers concluded that the sex scandal story, when presented in a race-neutral way, boosted the participants' racial considerations in evaluating the candidates due to the sexual promiscuity stereotype. And because black candidates are also stereotyped as being liberal, study participants likely projected those views onto Obama as well.

"Messages that don't seem to denigrate African Americans can be potent because they manage to denigrate under the radar," Mendelberg said. The doubts raised by political opponents about Obama's statements that he was born in Hawaii and that he is a Christian "fit the category of implicit" messages that portray the president as ethnically different, she said.

Examining race, gender and civic debate

While political campaigns and elections often deal with mass media, other democratic processes involve interpersonal conversation, and Mendelberg's research on citizen deliberation examines some of these interactions. Examples of citizen deliberation include jury deliberations, municipal meetings and government committees.

Mendelberg currently is working on the Deliberative Justice Research Project, cosponsored by Princeton and Brigham Young University, which uses group experiments to examine the effect of gender on group deliberations. Researchers asks participants, as a group, to decide the fairest principles for income distribution in a new society and for their take-home earnings in the experiment. Then they are assigned a task and told its yearly salary, which is then recalculated according to their performance and the rules chosen by the group. After they perform the task and learn their "salary" before and after redistribution, participants are asked to rank the principles again and comment on their satisfaction with the group's decision.

Mendelberg also has examined group interactions in real-world settings, such as school board meetings. She has found that both race and gender affect outcomes of citizen deliberation, though in different ways.

"Race can make a big difference. For example, adding a Latino juror to a jury can change the outcome significantly even when the decision involves nonracial issues," she said. "But gender matters in more subtle ways. In many political settings where women are a minority, the average woman speaks less than the average man. … The more a person speaks, the more likely they are to be rated as influential by other participants. If women speak less, they are less likely to convince others and less likely to see their preferences enacted. Simple rules such as unanimous rule can help when women are a numerical minority."

Awareness of these group dynamics allows leaders of civic discussions to structure the conversations so that they are environments "where people become informed, well-reasoned and empowered citizens" and where all voices are heard, rather than forums for disempowering, polarizing and misinforming people, Mendelberg said.

Undergraduates (from left) Charles Wright, Danielle Pingue and Megan Bowen discuss the civil rights movement in Mendelberg's spring seminar "Racial Politics in the United States."

Mendelberg brings this awareness to her teaching by establishing ground rules for discussions in her classes, where views often span the ideological spectrum. This spring, she taught "Racial Politics in the United States," a weekly three-hour undergraduate seminar, where she and 11 students discussed topics such as race, ethnicity and immigration; racial stereotypes and the media; and minority candidates. Mendelberg told students that all views were welcome, and she made counterarguments when discussions became too slanted in one direction.

"Given the topics we covered in class, there was a wide range of opinions that emerged, said Danielle Pingue, a rising junior and major in the Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs. "Professor Mendelberg had each student lead discussion each week, which allowed a different vantage point to come to the forefront."

"The best classes I've taught are those in which students express diverse perspectives and engage each other directly," Mendelberg said. "When that happens, it's a wonderful teaching experience for me and a terrific learning experience for the students."