From the April 23, 2007, Princeton Weekly Bulletin(Link is external)

Investigating where she comes from is a central theme for Anne Cheng(Link is external), an Asian American, who uses her wide-ranging interests in 20th-century American literature, film, psychoanalysis, history, law and the arts to explore how racial identity is perceived and promulgated in American culture.

Part of where she comes from is Princeton.

Cheng earned her bachelor’s degree in English, summa cum laude, from the University in 1985. She returned to Princeton last fall as a professor of English(Link is external), becoming the first tenured faculty member in the department to specialize in Asian American literature. She is also a core faculty member in the Center for African American Studies(Link is external).

Cheng’s office in McCosh Hall is familiar to her; until recently it was occupied by John Fleming, emeritus professor of English and comparative literature, who taught her Chaucer. Since being back on campus, Cheng has reconnected with other teachers who helped her develop her intellectual roots.

There is Maria DiBattista, a departmental colleague and ongoing role model, who helped her realize that women could thrive in an academic setting. There also are Michael Cadden in theater and dance, P. Adams Sitney in visual arts and Samuel Hunter, emeritus professor of art and archaeology, who were instrumental in opening Cheng’s eyes to new ideas that would shape her professional life.

The establishment of the new Center for African American Studies makes this an especially opportune time for Cheng to be at Princeton, where the dialogue about racial dynamics in the United States promises to deepen and expand. Committed to a comparative approach in her scholarship and teaching, Cheng is bringing new perspectives to the discussion.

“I believe the center welcomed me because I am interested in thinking about African American studies as an interdisciplinary field — in understanding African American history and literature as part of a larger American racial dynamic,” Cheng said. “Race studies have been around for 50 years, at least. Princeton wants to take a step ahead and ask, ’What does it mean to do race studies today?’”

Valerie Smith, the Woodrow Wilson Professor of Literature in the English department and the director of the Center for African American Studies, said Cheng is “one of the leading scholars working on the politics of racial identity and psychoanalysis.” She added, “We can always count on Anne to ask bold and probing questions and to imagine exhilarating, unconventional and paradigm-altering courses, programs and conferences.”

Finding a voice

Cheng came back to Princeton from the University of California-Berkeley, where she had been on the faculty since 1995, following a year teaching at Harvard. She earned her master’s degree in English and creative writing from Stanford and her Ph.D. in comparative literature from Berkeley.

At age 12, Cheng and her family emigrated to the United States from Taiwan, settling in Savannah, Ga. She did not speak a work of English.

Her father’s immediate task was to hire an English language teacher — a native Parisian who also ended up teaching Cheng French. “I went from learning to read Dr. Seuss to D.H. Lawrence to Proust,” Cheng said.

While her family adjusted to their new home, Cheng marveled at how rarely her parents asked about her homework, something they regularly had done in Taiwan. “Their expectations changed. They only hoped that my brother and I would survive the dislocation,” she said.

Then in high school, Cheng read Ralph Ellison’s “Invisible Man,” which changed her life.

“I thought I loved it because he was a great writer,” she said. “Later I realized that there was a deep reason for my interest in Ellison — it was because of his explorations of the politics of inclusion and exclusion.”

At Princeton and as her studies progressed, Cheng noticed that she was drawn to those characters in books who “seemed to fall out of time or plot.”

Emotionally and intellectually, she was starting to engage more deeply with her own identity, and what it meant for her to be both American and, specifically, Asian American.

In her book, “Melancholy of Race: Assimilation, Psychoanalysis and Hidden Grief,” which was published by Oxford University Press in 2000, Cheng connects the emotional with the intellectual in exploring the discourse on race, using Freudian psychoanalysis as a starting point.

“Psychoanalysis raises questions about identity and provides a certain vocabulary that is crucial to thinking about racial dynamics — vocabularies about desire, fear, revulsion — some of the psychical elements of race relations that link to the material aspect of race in America,” Cheng said.

Examining what she calls “racial loss,” Cheng studies the differences between the language associated with racial “grievance,” which typically has legal and quantitative connotations, and racial “grief,” which has emotional and qualitative connotations.

“In the United States we are very comfortable with the language of grievance, but not with the language of grief,” she said. “Focusing solely on grievance is a way to not talk about grief. It’s easier to say, ‘This is what’s wrong,’ rather than to talk about how this wrong has affected me, the person I am.”

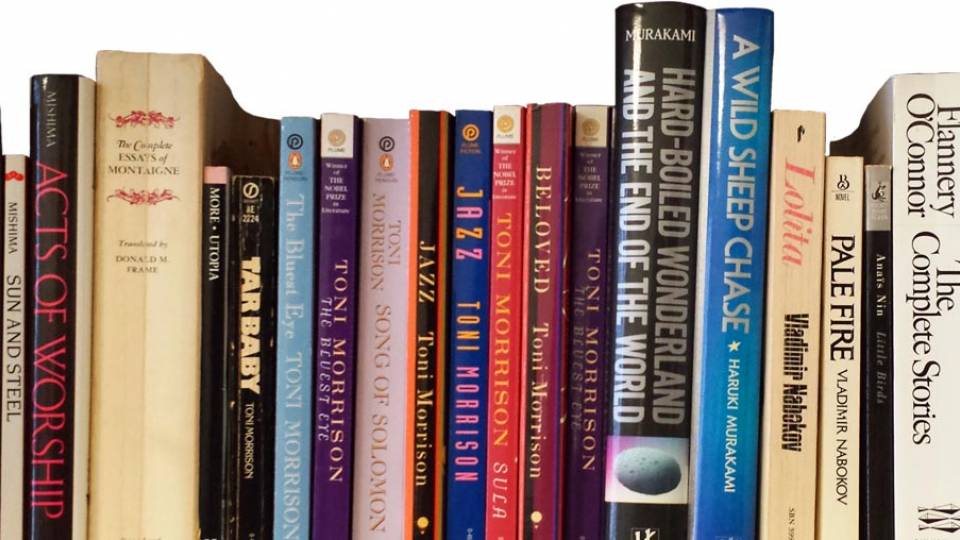

Cheng uses literary figures to illustrate the grief associated with racial loss, such as the feeling of not being seen, or of not being considered good enough. She points out that such grief is experienced by Ellison’s invisible man; by the African American girl in Toni Morrison’s “The Bluest Eye,” who prays each night for her brown eyes to turn blue; and by the narrator in Maxine Hong Kingston’s “The Woman Warrior,” who abuses an Asian American girl at school because she reminds her of herself.

Making connections

Professor of English Diana Fuss said Cheng’s presence is generating new intellectual possibilities. “Anne has already made her mark, bringing a new sense of excitement to a department in which she was once herself a star undergraduate,” she said.

Describing Cheng as “a genuine intellectual border-crosser,” Fuss noted how her work “stages serious encounters between figures one might not ordinarily put together — [Princeton creative writing professor] Chang-rae Lee and [French psychoanalyst] Jacques Lacan make an inspired pair.”

Michelle Coghlan, a doctoral candidate in English who is in Cheng’s class “Race and Psychoanalysis,” said that what she finds most compelling about Cheng’s work is how she “productively and proactively questions the boundaries of categories and disciplines, and encourages her students toward genuine interdisciplinarity.”

A current undertaking of Cheng’s that speaks to her intellectual elasticity is her new book project on Josephine Baker, who danced and sang her way to fame in Paris — most famously in a banana skirt — in the 1920s. What engages Cheng about the African American performer is not so much her biography, but the implications behind the vastly different responses she solicited as a cultural icon.

“On the one hand she is seen as this terrible fetish, an embarrassing primitivist figure, a sellout,” said Cheng. “And on the other hand she’s seen as powerful and subversive, especially due to her work with the French resistance during the Second World War.”

Faced with these conflicting viewpoints, Cheng asks, “What are our cultural assumptions about race and sex that have allowed this paradox to exist, and what do these assumptions teach us about the politics of representation and the interface of primitivism and modernity?”

Cheng also grapples with the contradictions that infuse the politically charged language used in America to talk about race. She observes that “the discourse about race, whether from the conservative side or the liberal side, is always passionate but often unexamined.”

She notes that even “progressive language about marginalized subjects tends to reproduce the stereotypical language it is trying to critique in the first place.” As an example, she points to the so-called affirmative rhetoric about Asian Americans as “studious” and as the “model minority.”

“This is just offering a positive image in the place of a bad one, but it is still a stereotype,” Cheng said. “With my work, I want to give people the vocabulary to understand the limitation in these kinds of identities.”

In her current undergraduate class, “Shades of Passing,” Cheng delves into many of these complexities, inspired by novels such as Chang-rae Lee’s “A Gesture Life,” William Faulkner’s “Light in August,” Toni Morrison’s “The Bluest Eye,” and films such as Woody Allen’s “Zelig” and Douglas Sirk’s “Imitation of Life.”

Upcoming courses she plans on teaching include exploring Chinatown as a “historical and imaginary construction”; studying the staging of race and gender in American film comedies from different ethnic traditions; and “looking at how style might inform rather than merely reflect racial and gender expectations,” as seen through the diverse examples of Josephine Baker and Edith Wharton’s “The House of Mirth.”

Cheng, who received an award for her student mentoring at Berkeley, is the adviser for English major Sunshine Yin’s junior paper, which compares Chinese short stories of the Ming dynasty with contemporary short stories in English.

Yin said she is “privileged to be able to work with Professor Cheng because of her background in both Chinese and English literature.” She added, “Professor Cheng is extremely vivacious and knowledgeable, and is just spilling over with intriguing ideas for me to take in new directions.”

Cheng also is enabling broader conversations on campus that speak to her far-reaching interdisciplinary interests. She has started a public lecture series called “Critical Encounters,” where invited speakers conduct conversations across the disciplines. Already, a historian and a novelist have discussed their research on slavery, and earlier this month Cheng talked about Constitutional history and its relationship to racial discrimination with Kenji Yoshino, a law professor at Yale.

Cheng may be back to where her scholarly career started, but she is in a very different place. “I never wanted to be an academic when I was growing up,” she said. “But now I know it is a luxury to have a profession that nourishes my inner life and a privilege to be able to raise difficult questions about the world in which we live.”