Spam — that shelf-stable "miracle meat" — made its way to Hawaii with the U.S. military as part of standard rations during World War II. The soldiers eventually left, but Spam entered the Hawaiian diet permanently. Spam musubi — made by wrapping nori, or seaweed, around a pan-seared piece of Spam on top of a small rectangle of sticky rice — is one of Hawaii's best-known foods.

Spam musubi also ended up as a final project for one group of Princeton students in the spring course "Food, Literature and the American Racial Diet" taught by Anne Cheng, a professor of English and African American studies. The class embarked on a comparative racial-ethnic literary journey, delving into works by Asian American, African American, Jewish American and Latino authors, journalists and film directors.

Assignments included writing analytical essays, experimenting with food writing, and conducting research into the history of food, which, noted Cheng, is often a history of imperialism and colonization. For their final project, students went food shopping, rolled up their sleeves and created dishes that illustrated some aspect of how food interacts with racial identity.

Divided into 30 small teams, the students discussed readings and shared their own experiences with culture and food. As part of a new Campus Dining initiative led by Executive Director Smitha Haneef to support students' academic experience, each team was paired with a chef who advised them on food ingredients, preparation and presentation. The dishes were presented and tasted at the "Princeton Feast" held April 30 in the Frist Campus Center.

Below are highlights of the "Princeton Feast," including audio clips of students talking about the dishes they prepared, a peek into the kitchen with one group who learned how to make traditional Neapolitan pizza, and insights from Cheng and Haneef.

A culinary-literary experiment

The multipurpose room in Frist Campus Center resembled the bustling floor of a convention center food show. At long tables, the student groups set up their dishes alongside a written explanation of their project. Students, faculty and staff roamed the room, indulging in bite-sized samplings of dishes while listening to the students explain the inspiration for their choices.

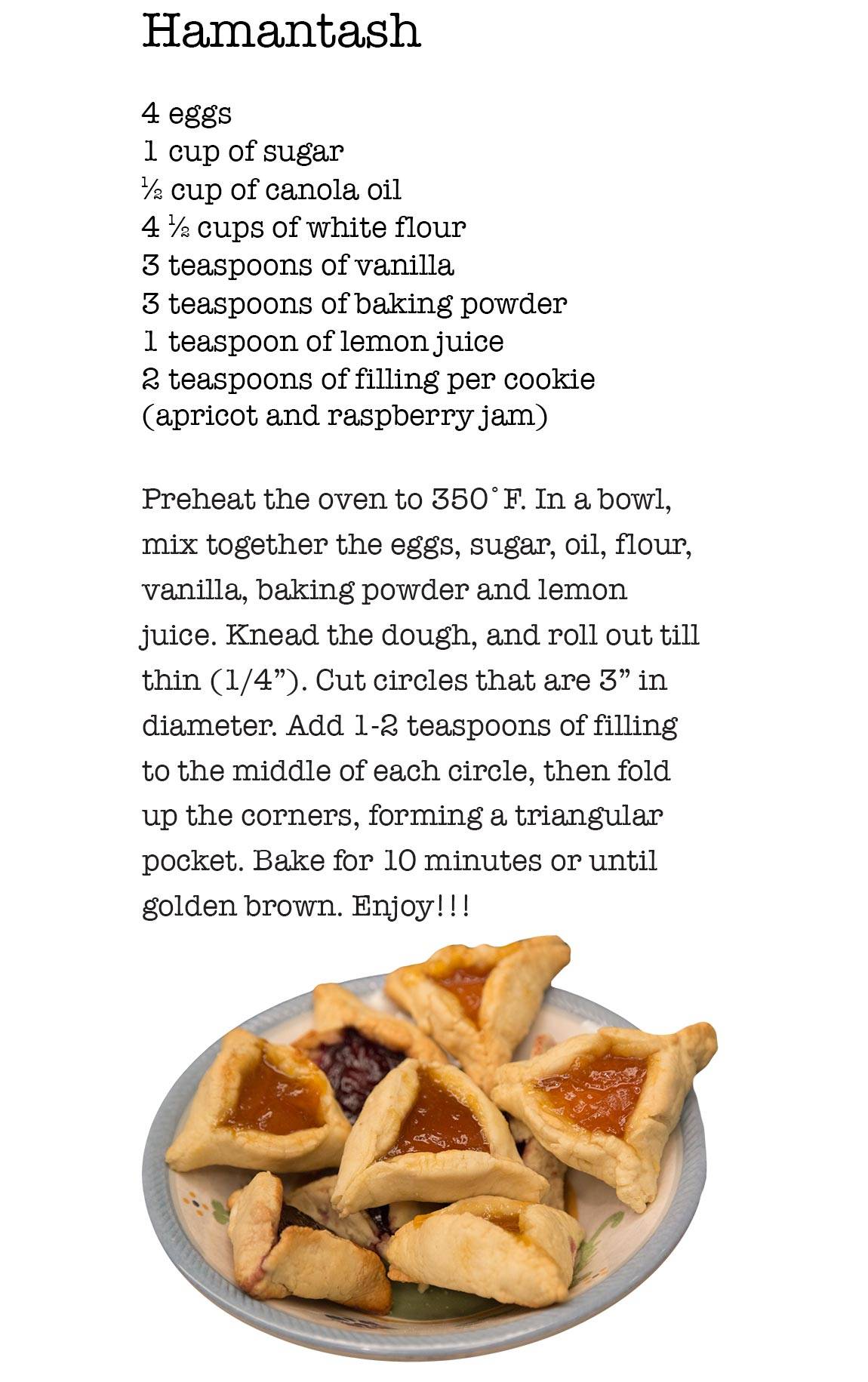

Hamantash. One team baked the Jewish dessert Hamantash — a cookie resembling a tri-cornered hat that is eaten during the Purim holiday and symbolizes Haman, a figure who plotted against the Jews but was foiled. The group compared the consumption of this pastry to the candy eaten by a character in "The Bluest Eye" by Toni Morrison, one of the assigned books for the class. See the end of the story for the recipe of Hamantash provided to the group by Gitty Webb, the wife of Rabbi Eitan Webb of Princeton's Chabad House.

Listen: Kate Prucnal, Class of 2015, tells the story of her team's dish, the Jewish dessert Hamantash.

Janet Schirm, a member of the Class of 2015 (left), and Gabriela Villamor, a member of the Class of 2016, pose with their identically tasting blueberry pies — one "conventionally attractive," the other not — to illustrate the theme of racialized beauty standards in Toni Morrison's novel "The Bluest Eye."

Blueberry pie. Another team baked two identically tasting blueberry pies — one "conventionally attractive" and the other not — to illustrate the theme of racialized beauty standards in "The Bluest Eye."

Listen: Mathilda Lloyd, Class of 2015, compares blueberry pie to the racialized beauty standards in "The Bluest Eye."

The dishes were presented and tasted at an event called the "Princeton Feast" held April 30 in the Frist Campus Center, attended by students, faculty and staff. Above, the Cookie Sushi team's written explanation of their project stands beside bite-sized samples for visitors to try.

Cookie sushi. Another team was inspired by the depiction of sushi in the short story "Bottles of Beaujolais" by David Wong Louie and created their own fusion dish to explore culture as a fluid, dynamic concept.

Listen: Rebecca Schreff, Class of 2015, describes how her team mixed ingredients from diverse cultures to make a fusion dish, cookie sushi.

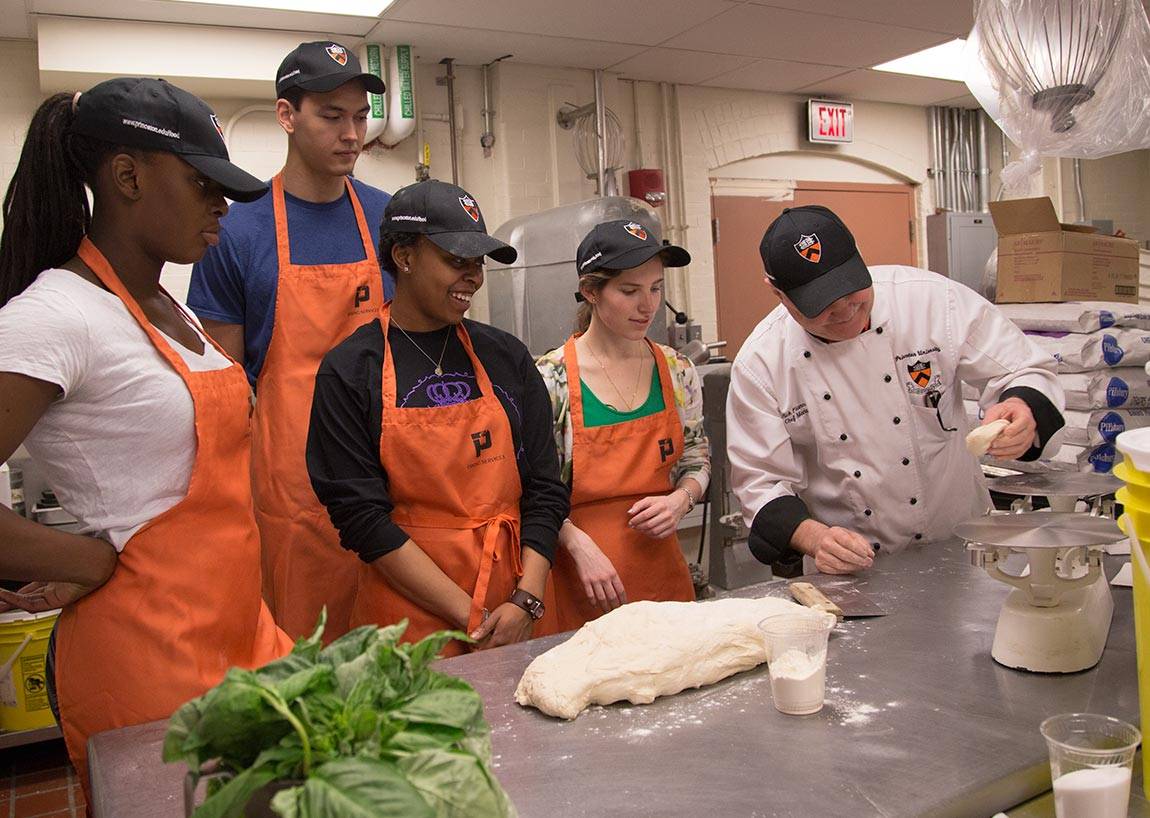

Each team was paired with a chef from Campus Dining who advised them on food ingredients, preparation and presentation. From left, Chelsea Johnson, Class of 2018; Alexander Schindele-Murayama, Class of 2016; Dominique Ibekwe, Class of 2016; and Cordelia Orillac, Class of 2015, get a lesson in making traditional Neapolitan pizza dough from Chef Rick Piancone, in the kitchen of Rockefeller and Mathey colleges.

In the kitchen: The Americanization of pizza

One group chose to compare two kinds of pizza: Neapolitan pizza prepared with traditional ingredients — very finely ground 000 flour, San Marzano tomatoes from Italy, fresh mozzarella and fresh basil — and the typical Americanized version, which uses commercial ingredients such as baker's dough with added sugar, sugary processed tomato sauce and packaged pre-shredded mozzarella.

The students met with chefs Rick Piancone and Mike Gattis in the kitchen at Rockefeller and Mathey Colleges and gathered around a large metal worktable and industrial mixer.

Dominique Ibekwe, a member of the Class of 2016, said: "We wanted to do pizza because it's a familiar comfort food that has been very commercialized. The chefs taught us how the art and craft in traditional Neapolitan pizza compares with the U.S. version and how the taste changes."

Chef Piancone tore off a little piece of dough for each student to feel. "The way you test the dough is with your hands," he said. He added flour. "Now you see it starts to feel more pliable." He asked a student to grab some olive oil and added a splash to the dough. "In two minutes I'm going to put it on high speed and really activate that gluten." He indicated the huge mixer, saying, "This machine is a workhorse."

Chef Gattis told the students that dough made with 000 flour needs to rest or "proof" for three days in the refrigerator. "It will get the consistency of an English muffin, very airy. Commercialized pizza uses all-purpose flour, not as fine. 000 is more like talcum powder. The fresh Buffalo mozzarella and San Marzano tomatoes contrast with the pre-shredded mozzarella that has a coating of flour as well as tomato sauce that has added sugar. Also, our whole being goes into the preparation — that's the difference between ours and the commercial version," he said.

"We're exploring the process," Ibekwe said. "You have to engage all your senses."

Listen: Chelsea Johnson, Class of 2018, describes reactions to both pizzas at the Princeton Feast.

David Exume, a member of the Class of 2018 (left), and Jessica McLemore and April Liang, members of the Class of 2015, pose with their dish, Spam musubi — a combination of Spam, which made its way to Hawaii with the U.S. military during World War II; rice; and seaweed molded into a sushi-like snack food.

Exploring the ways food engages the literary mind

This is the second time Cheng has taught this class. Here she expands on the link between food, literature and race:

The relationship between food and literature runs deep. When Virginia Woolf gets a rejection letter — and even the great ones get rejections — she goes and cooks haddock and writes a beautiful little song, an homage, to a filet of sole. Sylvia Plath's favorite book in the world is "The Joy of Cooking," which she calls a "big, juicy novel." And when she chooses to die in her kitchen, that makes its own statements about femininity, domesticity and hunger.

This class looks at how the intimacy between literature and food informs large social categories such as race, gender, sexuality, class and nationhood. For example, "The Bluest Eye" by Toni Morrison [Princeton's Robert F. Goheen Professor in the Humanities, Emeritus] gives us a complicated tale about white beauty and racial preference and their impact on black women and girls. One of the characters longs for blue eyes because she thinks that means approbation; yet another girl destroys white dolls out of a fierce sense of self-preservation. All these forms of emotional hunger and social consumption get played out through conceits about food. For one character, eating the candy called Mary Janes — these little candies that have a little blond, blue-eyed girl on the wrapper — feels like imbibing white beauty. But the "swallowing" does not go down easy: we find the little girl eating her candy with pleasure and pain, anger and desire — a complicated moment of internalization. The little black girl eating Mary Janes dramatizes both an act of self-fulfillment and self-erasure.

The challenge of this class is to think about the relationship between race and food beyond that of a simple equation between food and identity, beyond a cultural tourism, where one imagines that you get to take in another culture simply by eating its food. Instead, this class explores food as a complicated engagement with difference. Rather than looking at eating as a literal act, we examine the various ways in which we incorporate others into ourselves. This course explores both the joyful and the dark sides of eating and traces how "taste" informs the various ways in which we ingest the world and specifically "racial otherness."

Integrating Campus Dining with academic study

Haneef, who came to Princeton in 2014, explains her commitment to partnering with faculty members to enrich students' academic experience:

As part of the Campus Dining Transformation Plan, my strategic plan for the department, we have identified food as a subject of critical inquiry. Our vision is to provide support to the faculty in support of academic teaching and research in the subject of food, food systems and food experiences. Princeton Feast is a great example of this. Through this collaboration with Campus Dining the goal is to combine practice with research, to encounter food as material and as a critical site for reflection.

The students in the class were partnered with members of the Campus Dining Culinary Council — a consortium of nine senior chefs, which I lead. As subject matter experts in the field of food production, our Culinary Council is able to engage the students to support them with their course work.

Campus Dining has also partnered with other faculty members. This spring, for example, I gave a presentation on culinary principles for healthy and sustainable menus for the energy and environment course "Designing Sustainable Systems: Applying the Science of Sustainability to Address Global Change" taught by Forrest Meggers [assistant professor of architecture and the Andlinger Center for Energy and the Environment].

Anne Cheng, professor of English and African American studies (third from right) and Smitha Haneef, executive director of Campus Dining (second from right), listen to students discuss the inspiration for their dish. Chef Rob Harbison, the executive chef of Campus Dining (far right), was among the chefs who consulted with the student teams.

Food as a means of creating community

Cheng and Haneef see food and cooking as a way of creating community inside and outside the classroom.

"I think it's great for the students to work with the chefs," Cheng said. "There are all these different communities here — the students, the graduate students, the faculty, the staff — and they don't often connect altogether. I think the Princeton Feast is one of those special occasions where that can happen."

Haneef and her team work with students and faculty advisers in the residential colleges to cook communal dinners made with seasonal ingredients. In the fall, Campus Dining will create a special dessert, as they did last year, to debut with the Princeton Pre-read book for the freshman class, "Whistling Vivaldi: How Stereotypes Affect Us and What We Can Do." Other academic and co-curricular initiatives surrounding food and food preparation are planned.