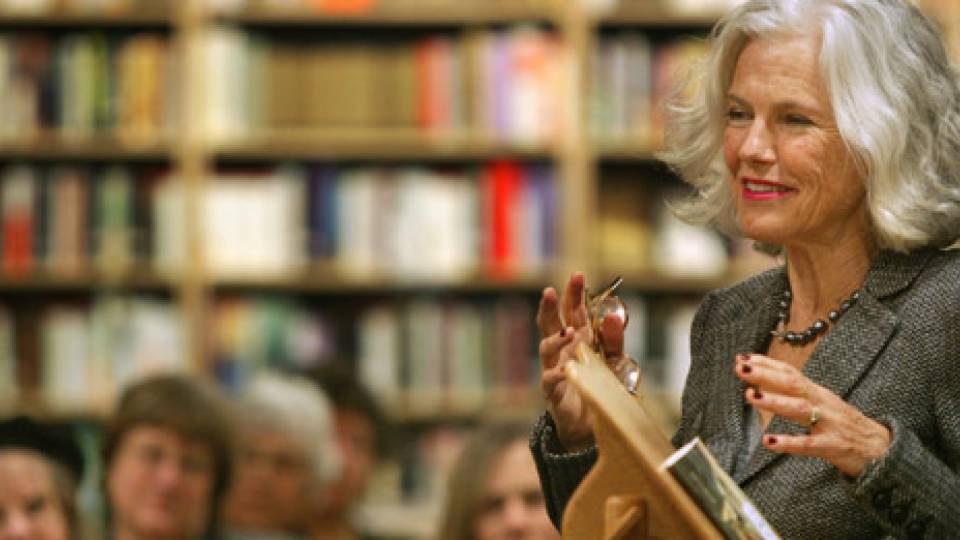

From the April 3, 2006, Princeton Weekly Bulletin

In his latest work, professor of creative writing Edmund White transports us to his childhood in Illinois in the 1950s — and to a world in which being gay was commonly viewed as something reproachful.

At age 14 or 15, after years of struggling with his identity, White told his mother that he was gay — or rather, homosexual. “That was the word, back then, homosexual, in its full satanic majesty, cloaked in ether fumes, a combination of evil and sickness,” White writes.

White’s mother, a child psychologist and divorcée who held nothing back from her son, sent him off to a Freudian psychiatrist and reported his diagnosis back to the teenager: He was “unsalvageable.”

So begins White’s “My Lives,” an autobiography as unconventional as its author, which is being published by Ecco Press this month. Rather than recount his life in chronological order, White — who already has been the subject of two biographies — offers chapters titled “My Shrinks,” “My Blonds,” “My Europe” and “My Hustlers.”

A professor at Princeton since 1999, White is known for autobiographical fiction such as “A Boy’s Own Story” and “The Beautiful Room is Empty,” lyrical novels that mine his experiences coming of age as a gay man. In the halls of 185 Nassau St., he is known as a dedicated teacher who is attentive, supportive and candid with his students.

In “My Lives,” White doesn’t attempt to map the business of his life with dates and places. Nor does he spill much ink discussing the typical fare of many writers’ autobiographies, such as how he got his first novel published or how he approaches the creative process.

“I primarily wanted the book to be entertaining,” White said. “I’ve always wanted everything I wrote to be entertaining — not on a vulgar level, but on a high level, if you will, something that will engage your feelings and your intellect and your passion all at once.”

As a writer on the vanguard of the gay rights movement, White felt the book needed “a lot more about relationships and sex and probably a little less about the professional details of my career.”

There are some graphic scenes depicting White’s sex life, but the most compelling parts of the book are his characterizations of his parents: his mother, a squat, overdressed Texan whose “egotism and incessant chatter could be truly punishing;” and his father, a tyrannical, reclusive misanthrope whose son failed to interest him.

“I tried to portray them as honestly as I could, but it was painful going back into all that stuff, especially the chapter on my father. I never really let myself think that much about it,” said White, whose parents died more than a decade ago. He worried about his sister’s reaction to the book, but “after she read it, she said, ‘Oh God, you let our parents off so lightly. They were much more monstrous than that.’”

In England and Australia, where “My Lives” was published last year, it has been called “a vital and engrossing book” by The Guardian, while The Australian dubbed it “White’s best book, the one that channels his finest writing.” Excerpts have appeared in The New Yorker, Granta and Ontario Review, which is co-edited by Joyce Carol Oates, the Roger Berlind ’52 Professor in the Humanities.

Oates and White are close friends who often read each other’s work in its early stages.

“She’s incredibly warm and welcoming and a lot of fun,” White said of Oates. “She’s a great friend and a very discerning one who has been a real help to me with my writing, partly as an example. I think I’ve become much more productive since I’ve known her.”

Oates described White as “a remarkably generous reader of others’ work” and a “congenial, warm” colleague. “Edmund White is known in some quarters as a ‘revolutionary’ writer in the sense in which he has written frankly and without pretense of gay subjects, but perhaps more importantly, Edmund is a stylist in the precision of his language, and it’s likely to be for the writer’s unique voice that he is read and valued,” she said.

In this passage from “My Lives,” White describes Evanston, Ill., where he lived for part of his childhood:

“In Evanston there were hundred-year-old elms shading wood houses behind their underclipped hedges. Plain girls straddled cellos at home and practiced for hours. Boys wrestled with one another after school in piles of autumn leaves. Everything smelled of quietly smoldering leaves. Fathers were professors of geography at Northwestern. Mothers got out the vote for liberal causes.”

In addition to his eight novels, White has written several books of essays, a collection of short stories, a number of plays and two biographies, of Jean Genet and Marcel Proust.

Strategies for good writing

In the classroom, White is enthusiastic about his students’ work and offers meticulous criticism without coming across as harsh, said sophomore Chris Arp. “During our classes he listened as one listens to adults, and he was always careful and precise. Each student in our class blossomed in unique and exciting ways. Being in White’s class has, without a doubt, been the high point of my Princeton experience thus far.”

Many people contend that writing can’t be taught, but White said he does it by demonstrating to students that good writing has techniques they can learn.

“I think you can teach somebody as much how to write as how to paint or compose music,” he said. “The problem is since everybody can write a letter, they assume there’s no art to writing — it’s just telling a story the way you might recount an incident in a letter to a friend. But, in fact, there are all kinds of strategies — the use of dialogue, creating a character of suspense or mystery — that can be learned. We read short stories of established writers and analyze them, not as you would in an English class, for symbols and themes, but for writing tricks.”

His students relish the opportunity to delve into their imaginations. “Most of our students don’t want to become writers. What they really want is a moment in their Princeton career when they can express themselves and explore their own imagination,” he said.

And creative writing can become a forum for stimulating discussions of morality, White pointed out. “Looking at ethics is really looking at a particular moment in someone’s life, and fiction is almost an ideal medium for that. The students have some really interesting discussions about all kinds of issues.”

White currently is on leave from Princeton on a fellowship at the New York Public Library, where he is working on his next novel, “Hotel de Dream,” which takes place in the 1890s. The book begins with the writer Stephen Crane on his deathbed at the age of 28. In his delirium Crane is attempting to dictate something to his wife, which White imagines to be the unfinished novel he once wrote about a gay young man he met on a New York street corner who was prostituting himself.

“Crane had written 40 pages about this boy, and then Crane’s best friend, Hamlin Garland, a Wisconsin he-man writer, convinced him to tear the whole thing up,” White said. “Garland told Crane, ‘These are the best pages you’ve ever written, and if you write one more, you won’t have a career.’ This was 1895, the year of the Oscar Wilde trial,” in which Wilde was convicted of participating in homosexual acts.

White is consulting the New York Public Library’s collection of Crane’s letters. “I’ve become fascinated with the novel within the novel — the one that I’m calling Crane’s novel,” White said. “It’s sort of taken off and become autonomous.

“When you write a novel, the main thing you want to do is to silence the world and go really far inside yourself to find images, words, memories and observations that will be extremely resonant for you and, you hope, for your reader,” he said. “Anyway, I’m having fun with it.”