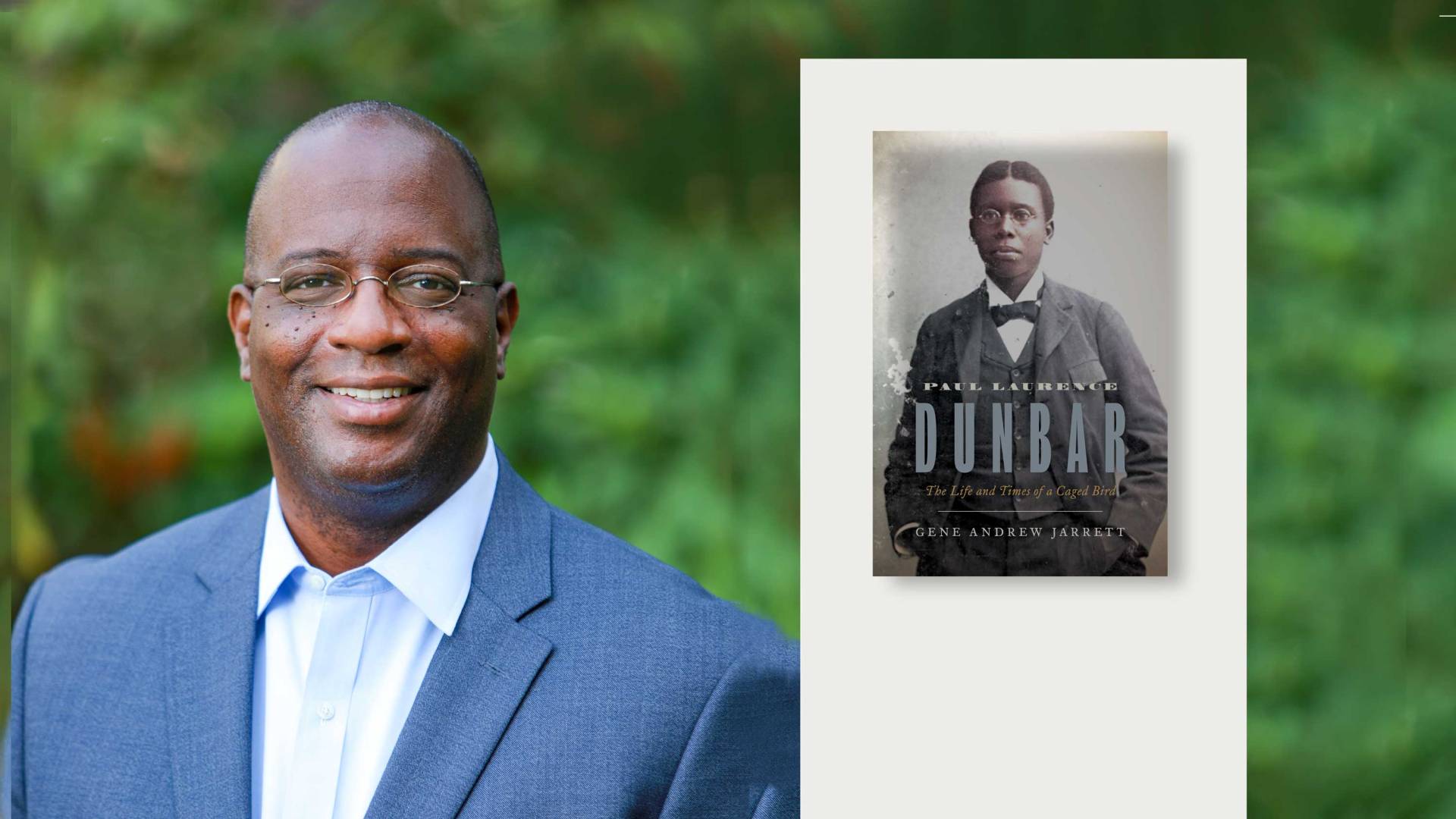

Gene Jarrett, Princeton’s dean of the faculty and the William S. Tod Professor of English, has taught students about Paul Laurence Dunbar for two decades and published book articles and chapters on the popular and accomplished writer. But it wasn’t until 2008 that Jarrett decided to tackle a biography of Dunbar, who rose to prominence in the Gilded Age.

The biography, “Paul Laurence Dunbar: The Life and Times of a Caged Bird,” was published in June by Princeton University Press and was recently selected as one of The New Yorker's best books of 2022. Other Princeton faculty with books on the list include Yiyun Li for "The Book of Goose," Fintan O'Toole for "We Don’t Know Ourselves," Imani Perry for "South to America," and Keith Wailoo for "Pushing Cool." Jarrett will appear Thursday, Nov. 3, at Labyrinth Books in Princeton, in conversation with Simon Gikandi, the Robert Schirmer Professor of English at Princeton.

Jarrett, a 1997 Princeton graduate who returned to the University last summer, said that the genre of biography allowed him to tell a new story of the complexities of Dunbar’s journey as a writer. Biography, which is “rooted in storytelling and scholarship alike,” as he writes in the book’s acknowledgements, allowed him to illuminate “those interior forces that guided [Dunbar’s] literary pen.”

Born during Reconstruction to formerly enslaved parents, Dunbar (1872–1906) excelled against all odds to become an accomplished and versatile artist and has been called the “poet laureate of his race.” But while audiences across the United States and Europe flocked to enjoy his literary readings, Dunbar privately bemoaned shouldering the burden of race and catering to minstrel stereotypes to earn fame and money. He died at the age of 33.

Below, Jarrett reveals the backstory of several moments in the book and reflects on how his Princeton professor Toni Morrison helped shape his own story as a writer.

This story is being published on the 150th anniversary of Dunbar’s birth. For all of Dunbar’s renown as a pivotal figure in American literary history, contemporary readers might not be familiar with him. What moment from the book do you think Dunbar himself would choose on his birthday to illuminate the impact of his life as a writer?

Of course, it is difficult to speculate on what Dunbar would choose, since he was such a complex person! However, I am inclined to say that he appreciated his own recurring literary success and wide impact on people who read his literature or those who listened to him perform it.

One moment that comes to my mind is his recitation of a poem, “Ode to the Colored American,” at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893. His mentor, the great African American orator and statesman Frederick Douglass, had just delivered an impassioned address, titled “The Race Problem in America,” in which he rails against the stereotypical images of African Americans at the exposition. Not only did Dunbar witness the greatness of Douglass’ ability to move a crowd with oratorical suasion; he recited his poem right afterward in commemoration of African Americans, including his father Joshua Dunbar, who fought decades earlier on behalf of the Union Army in the Civil War. An ovation followed Dunbar’s performance, signaling the pleasure of the audience with his verse but also its genuine recognition of his walking in Douglass’ footsteps — both literally and figuratively — on the public stage.

One of the lines from Dunbar’s 1899 poem “Sympathy” — “I know why the caged bird sings” — was made famous again in 1969 when Maya Angelou paid homage to it as the title of her first memoir. Your book’s subtitle refers to Dunbar himself as “a caged bird,” and in it you write about “the perennial relevance of Dunbar’s original song.” How does this poem strike you as a sounding bell of its own time that continues to resonate into the present moment?

The arc of historical meaning that connects Dunbar to Maya Angelou’s uses of the “caged bird” symbol is the individual’s struggle against societal prejudices: the degree to which a person, who has a unique sense of self and a set of future ambitions, is constrained by, or beholden to, the preconceptions imposed by the world.

Dunbar and Angelou ultimately employed this trope for different purposes: in one case, Dunbar’s poem presumably (if autobiographically) attests to the strife of a young Black man at the turn of the 20th century; and in the other case, Angelou’s work is an actual autobiography which conveys this circumstance in the life of a maturing Black woman in the modern era. I would argue that, beyond race and gender, this notion of a caged bird can have great universal meaning for individuals hailing from a variety of social backgrounds and identities.

In the Gilded Age, Dunbar won fame giving public readings of his work, but he came to regard the popularity of his poems in dialect as a curse as well as a blessing. While he knew white audiences loved lines like “G'way an' quit dat noise, Miss Lucy—/Put dat music book away...,” he was conflicted about being limited to this stereotyped genre when he knew his artistic gifts were deeper than that. What is an experience from Dunbar’s life that you pay special attention to in the book to show how this conflict played out in his writing?

The benefit of my biography is its insight to Dunbar’s private life through his letters of correspondence to family, friends and acquaintances. In this setting, we encounter, if you will, a truer, more authentic sense of his unvarnished views on the personal and professional challenges of writing literature when the commercial vogue for dialect, such as in the lines you excerpt, happens to be so strong.

In a March 1897 letter to an acquaintance, Dunbar remarked of William Howells, the so-called Dean of American Letters who could either make or break a literary career but also who happened to praise Dunbar’s 1895 book “Majors and Minors” in a book review: “I see now very clearly that Mr. Howells has done me irrevocable harm in the dictum he laid down regarding my dialect verse.” As much as Dunbar prospered from Howells’ review, he was haunted by its framing of his public persona as a dialect poet. Dunbar would capture this conundrum in the verse of a poem, “The Poet,” which he published in his 1903 collection “Lyrics of Love and Laughter”: “He sang of love when earth was young,/And Love, itself, was in his lays./But ah, the world, it turned to praise/A jingle in a broken tongue.”

Dunbar had some famous friends, including Orville Wright, Frederick Douglass, Booker T. Washington, Theodore Roosevelt and the British composer Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, among others. Would you share a detail about one of these friendships that you focus on to show readers a transformative moment in Dunbar’s journey as a writer?

Dunbar and Orville Wright were entrepreneurial partners in a short-lived newspaper which circulated in Dayton, Ohio, called the Dayton Tattler, in late 1890. They were classmates in Dayton’s Central High School and respected each other as collaborators: Dunbar edited the newspaper to cater to Dayton’s African American community; and Orville, along with his brother Wilbur, ran the shop in West Dayton where the paper was printed.

Not to leave you in too much suspense, but you can read my biography to learn about how a Black boy and a white boy, in Dunbar and Orville, improbably came together despite the specter of racial segregation in America, and how this relationship was a key backdrop to Dunbar’s transformation into a professional writer (and, it so happened, Orville’s own development into an iconic aviator).

In the book’s introduction, you call Dunbar, who died at age 33, a “prodigious and prolific” writer who produced “a body of work that showcased his mastery of literary genres.” Tell us about one of Dunbar’s poems, essays, novels, short stories or Broadway libretto or lyrics that has particular meaning for you.

Dunbar is understandably well known for being a poet, but, as you note, he was also a writer of other genres. His first novel, “The Uncalled,” was published in 1898 — right after his poems launched him onto the international stage — and it turned out to be a rather fine piece of literature.

Not only does the novel curiously avoid the traditional cast and vernacular of African Americans commercially expected of an African American author; it also tells the story of a young man whose race is not explicitly signified but whose life similarly, in an autobiographical way, reflected the issues Dunbar faced in his own life: the turbulence of living in a household with his parents, his vexed relationship to provincial life, and his spiritual anxieties about the perceived indignity of his past and how the latter can predetermine his future.

The novel contains the formal and thematic traits that one would encounter in the American naturalistic novels of the turn of the 20th century, such as by Theodore Dreiser and Stephen Crane, in which there is a presupposition of the environment compromising the strength of your agency to determine your own future. I have enjoyed studying and talking about Dunbar’s first novel in this way.

Toni Morrison won the Pulitzer Prize in fall semester of your first year at Princeton, but you didn’t meet her until your junior year, when you took her class on “American Africanism,” which examined African American characters in American literature. Was there a moment while you were writing Dunbar’s biography when you felt Morrison on your shoulder or whispering in your ear?

Fascinating question! Well, there are different ways of interpreting what it means for a legendary figure to be peering over your shoulder as you seek to craft sentences. I will say that she had very high standards for her students and for fellow writers and scholars. I was honored to be her student at Princeton, to read her edits to my sentences and her marginalia beside my paragraphs, seeking to plumb the essence of my concepts and to hone the contours of my arguments.

As I have grown older and matured as a person and a writer, I am inclined to say that I endeavored in writing my biography to make her proud that one of her former students could excel in a genre that seeks, in a way different from her fiction but still in the same mode of thinking and expression, to paint the full life and times of an individual. I could well imagine that she would have despaired over how some of my sentences ultimately sprawled onto the page. On the other hand, I am hopeful that she also might have appreciated the other sentences as promising examples of the inevitable pain and pleasure that result from any serious literary attempt to pen the right word at the right time.

This story first appeared on princeton.edu on June 27 and has been updated with details of The New Yorker recognition and upcoming author appearance.