Revamping the K-12 education system and improving federal research

funding are crucial to maintaining America's edge in innovation and

competitiveness, Princeton President Shirley M. Tilghman said in a

panel discussion Wednesday in Washington, D.C.

The discussion on "The Importance of Innovation to the Future of the

Nation" at the Library of Congress was organized by Microsoft to kick

off its Tech Fair 2005.

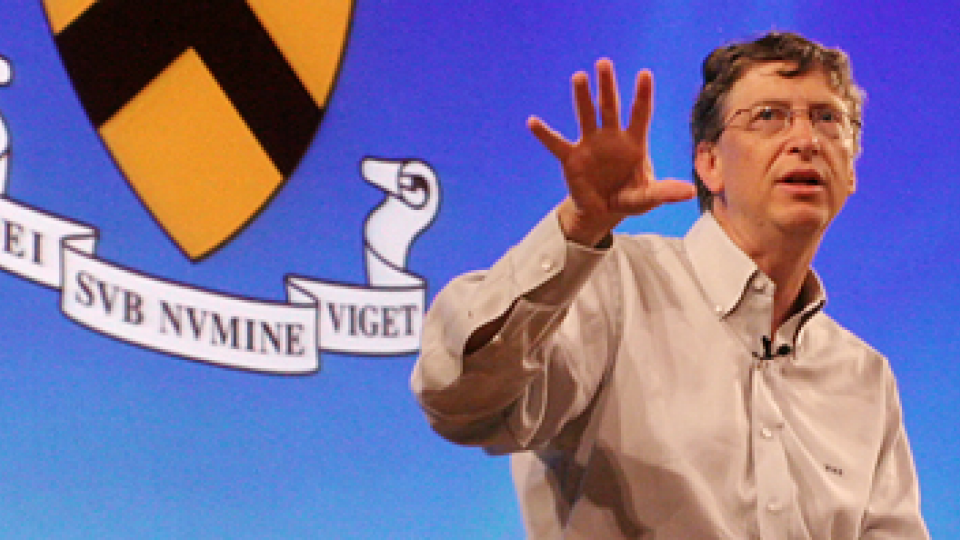

It opened with comments by Microsoft Corp. Chairman and Chief Software

Architect Bill Gates, who termed today's climate for innovation "a bit

scary," noting a declining interest in science among U.S. students as

well as a downturn in investment in education and research. "We're

quite concerned that the U.S. will lose its relative position in

something that's very critical to the economy," he said. "The

high-paying jobs are there, but the pipeline is just not what it needs

to be."

Tilghman said that universities are doing a "stellar job" of training

scientists and engineers, but that students often lose interest in

those fields long before they reach the postsecondary level.

"There's a deep paradox in American society," she said. "The United

States has the finest higher education system in the world -- that’s

indisputable. We have a really failing K-12 education system, and

that's simply incompatible with the long-term goals" of remaining

globally competitive in science, technology and innovation.

"Too often, by the time they get to us, [students] are 'mathphobic',

they're 'sciencephobic,' despite the fact that I'm convinced many of

them have the talent to become great scientists," added Tilghman, a

world-renowned scholar and leader in the field of molecular biology.

Gates and Tilghman also pointed to another pipeline problem: the

declining number of students from other countries who study science

here and stay in this country. Tilghman said that the number is

shrinking in the wake of post-9/11 changes in visa policy. She cited a

report issued last month by the Council of Graduate Schools indicating

that there was a 5 percent decline in international graduate student

applications in 2005, following a 28 percent decline in 2004.

In addition, she said that many of the international students who

graduate from universities in this country are finding better

opportunities back home than they once did, reducing the pool of

talented scientists and engineers who remain in the United States.

Other panelists for the program were: U.S. Sen. Patrick Leahy of

Vermont; U.S. Rep. David Dreier of California; Phillip Bond,

undersecretary for technology in the U.S. Department of Commerce; and

Rick Rashid, senior vice president of Microsoft Research. The

discussion was moderated by James Fallows of The Atlantic Monthly.

Turning to the topic of federal funding for basic research, Tilghman

agreed with other panelists that investment in high-risk research is

pivotal to major advances in technology. She pointed out, however, that

the largest source of federal funding for this type of research comes

from the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, which has been cut

by 20 percent in President Bush's fiscal year 2006 budget request.

She added that the country needs to make an investment where the "focus

is long term and the vision is bold," citing energy research as an area

that needs significant attention, given the 50-year outlook for the

availability of fossil fuels.

During the audience question-and-answer period, Tilghman was asked if

she thought the U.S. over-invests in health research and under-invests

in physical science research. "We don't over invest in health research,

but we do under-invest in the physical sciences -- and that really does

have to change," she said.

On the issue of increasing the number of women in science and

engineering, Tilghman said, "There is an enormous amount we can do."

She credited former Massachusetts Institute of Technology President

Charles Vest for bringing the issue to the fore, and said that most

major research universities are now working very hard on a number of

initiatives to encourage more women to pursue careers in science and

engineering.

"If you need a good reason why we should do it, it comes back to

manpower (or womanpower) issues," she said. "If we are essentially

ignoring half of the population as a potential pool from which to draw

scientists and engineers, we will have a less distinguished scientific

enterprise."

Tilghman was asked at what point girls appear to lose interest in math

and science. She said that there seems to be a drop-off at every level

-- from middle school to graduate school. "There's no period in the

entire career path where work does not need to be done," she said.