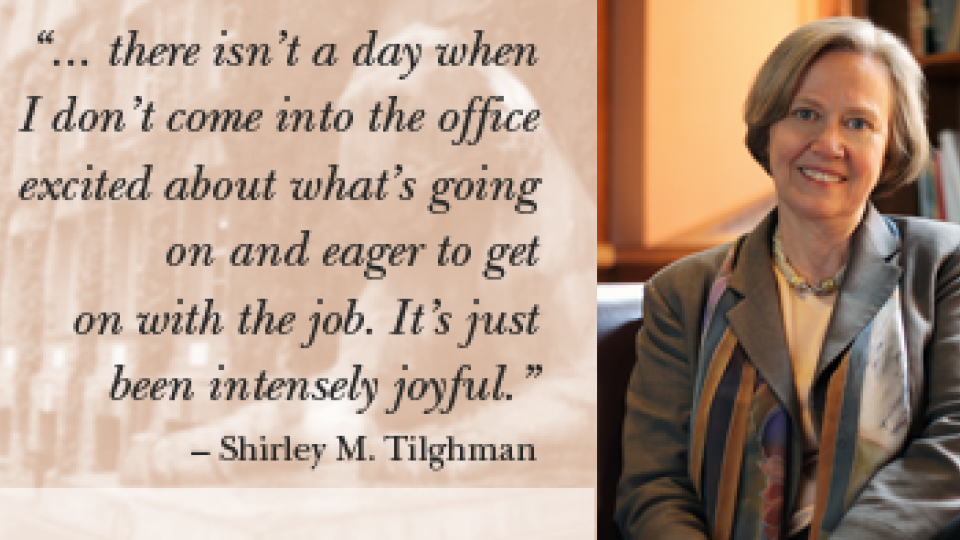

In a recent address on the under-representation of women in science

and engineering, Princeton University President Shirley M. Tilghman

offered "a rationale for why universities in particular and Americans

in general should care about this issue."

Tilghman spoke March 24 at the launch of the ADVANCE Lecture Series at

Columbia University's Earth Institute, part of a program intended to

increase the recruitment, retention and advancement of women scientists

and engineers.

"First and foremost," she said, "the future vitality and prosperity of

the United States fundamentally depend upon the scientific and

technological creativity and innovation that is nurtured within its

research universities. Universities like ours are the research engines

of this country, a role that is based on a social contract between the

federal government and universities that was forged just after the

Second World War. … For this partnership between universities and

government to thrive in the 21st century, we will have to attract into

science and engineering more than our fair share of the best and

brightest young minds from all over the world.

"To restrict the pool, either intentionally or unintentionally, by

discouraging women – or under-represented minorities for that matter –

from pursuing careers in science and engineering is to guarantee

that the outcome, and thus the future prosperity of the United States,

will be less than it could be," Tilghman said.

The full text of her speech, "Changing the Demographics: Recruiting,

Retaining and Advancing Women Scientists in Academia," is posted below.

Good afternoon. I am delighted to be able to join you for the launching of your ADVANCE program to strengthen the presence and enhance the experience of female scientists and engineers at Columbia University. I must say, however, that when I accepted this invitation in the fall, I did not foresee that speaking as a university president on the subject of the under-representation of women in science and engineering would become a form of risk-taking behavior that makes bungee jumping and going over Niagara Falls in a barrel seem like child’s play.

I want to begin with the images of the women on the first slide. These

are among the most successful women working in the fields of science

and engineering today – Linda Buck, who received the Nobel Prize in

Medicine last year for her work on the molecular basis of olfaction;

Jackie Barton, a member of the National Academy of Sciences and a

chemist at Caltech; Ingrid Daubechies, a mathematician at Princeton and

another NAS member; Barbara Meyer, a NAS member and brilliant

geneticist; Barbara Grosz, a computer scientist who works on artificial

intelligence and serves as Dean of Science at the Radcliffe Institute;

Sharon Long, a NAS member and plant biologist who is Dean of Humanities

and Sciences at Stanford; Vera Rubin, an astrophysicist and NAS member;

Susan Kieffer, a geoscientist at Illinois and NAS member; Liz

Blackburn, a cell biologist whose discovery of telomeres has won her

many wards, including membership in the NAS; and Pam Bjorkman, a

structural biologist and a very young NAS member at Caltech. While

hardly a random sample, this slide could have included dozens of other

successful women scientists.

I wanted to have their images in our minds during my address because in

our eagerness to find ways to increase the participation of women in

science and engineering, we should not lose sight of how far we have

come. This slide could not have been constructed 30 years ago when I

was completing my Ph.D., and I find the successes of the women it

depicts to be a tremendous source of inspiration and guidance going

forward. Last spring, the first woman in the history of Princeton

University to be granted tenure, Professor of Sociology Suzanne Keller,

retired. When describing the Princeton of 1966, when she joined our

faculty, she commented, “I really thought I was from Mars. It was as if

the men had never seen a woman.” Today, within the span of one career,

105 members or just under 20% of Princeton’s tenured faculty is female,

28% of the junior faculty are women, and last year 36% of all new

appointments to the faculty were female. Two traditionally male

domains, the School of Engineering and Applied Science and the Woodrow

Wilson School of Public and International Affairs, are currently headed

by female deans. Today’s Princeton would be unrecognizable to the young

Suzanne Keller, and that alone gives me enormous hope for the future.

In thinking about this talk, I concluded that it made little sense for

me to review once again the numbers – I suspect everyone in this

audience knows them by heart. Instead, I want to begin with developing

the rationale for why universities in particular and Americans in

general should care about this issue.

First and foremost, the future vitality and prosperity of the United

States fundamentally depend upon the scientific and technological

creativity and innovation that is nurtured within its research

universities. Universities like ours are the research engines of this

country, a role that is based on a social contract between the federal

government and universities that was forged just after the Second World

War. New industries that were born in this country and grew up in the

second half of the 20th century – like the biotechnology industry, the

microchip industry, wired and wireless telecommunications, and internet

commerce – all have their roots in the work of faculty and their

students and fellows in universities like Columbia and Princeton. For

this partnership between universities and government to thrive in the

21st century, we will have to attract into science and engineering more

than our fair share of the best and brightest young minds from all over

the world. To restrict the pool, either intentionally or

unintentionally, by discouraging women – or under-represented

minorities for that matter – from pursuing careers in science and

engineering is to guarantee that the outcome, and thus the future

prosperity of the United States, will be less than it could be.

The second argument for increasing the participation of women in

science and engineering is that the scientific interests of women may

not be completely coincident with those of their male colleagues. I am

not suggesting that women conduct scientific inquiry differently from

men – the scientific method is universal – but it has been my own

experience that the problems that intrigue women about the natural

world are not always exactly the same as those that attract men. By

encouraging women to embrace science, we likely increase the range of

problems under study, and this will broaden and strengthen the entire

enterprise.

The third argument is unquestionably true. If women continue to be

under-represented in science, engineering, and mathematics, these

fields will look increasingly anachronistic to students, and we risk

losing the most talented among them, who will, after all, have an

infinite range of career options from which to choose. As law, medical,

and business schools reach gender parity in their student bodies,

science and engineering will become increasingly unattractive vis-à-vis

those fields. Today the difference is there for all to see. For

example, the Association of American Medical Colleges reports that

45.2% of medical school graduates in 2003 were female, whereas,

according to the American Society for Engineering Education, only 17.4%

of Ph.D. degrees in engineering were awarded to women that year.

I am reminded here of one of the reasons that was offered as to why the

schools in the Ivy League became co-educational. It was argued at the

time that the schools were afraid that they would lose the most

talented male students to co-educational schools. Now, as a reason to

admit women, it may not ring with high principle, but it was a

realistic concern. Those schools back in the late 1960s knew that men

did not want to be educated any longer only with men.

Finally, it is simply unjust for a profession to exclude – whether by

sins of commission or omission – a significant proportion of the

population on the basis of gender. For every girl who dreams of

becoming a scientist or engineer, there is a moral obligation on our

part to do everything we can to even the playing field so her chances

rest on her (dare I say innate?) abilities and her determination, just

as it does for her male counterparts. It is not sufficient to shrug our

shoulders, invoke all the historical reasons for the situation, call

upon the leaky pipeline, or bemoan the difficulty of changing culture.

As Pogo famously said, “I’ve seen the enemy, and he is us.”

The under-representation of women in science and engineering has many

causes, some of which are rooted in childhood, when boys and girls

confront divergent parental, scholastic, and societal opportunities and

expectations. Indeed, part of our challenge is that universities stand

at the end of a long and imperfectly constructed pipeline that is

partially controlled by others, yet this does not excuse us from fixing

leaks – and there are many – in the section of the pipeline that we do

control. Nor should we forget that universities sit at the pipeline’s

terminus and, therefore, add more value to the knowledge flowing

through it than any other stakeholder.

When we place a premium on creating an equitable and supportive

environment for female students and scholars, when we empower women to

fulfill their potential in science and engineering, and when the human

face of these fields is diversified, we send a very powerful message

all the way back to the wellhead. The message we communicate is this:

women can and do excel in disciplines where men have long predominated.

So if you are persuaded that we have good reasons for making science

and engineering more inclusive, the question becomes one of “how do we

get there?” There is no silver bullet – no instantaneous solution – but

with determination and imagination, universities can surely change the

climate for women where they are under-represented. Programs like

ADVANCE will help Columbia University and, indirectly, all of us to

identify the ways in which universities must change in order to achieve

better representation of women in science and engineering. I salute Lee

Bollinger, Jean Howard, and Robin Bell for the dynamic leadership they

are providing.

The first and most intractable obstacle that many female scientists and

engineers confront in our institutions is the sheer fact that they are

sometimes overwhelmingly outnumbered by men. For, simply put, numbers

really matter. I suspect that most of us, male and female, black and

white, young and old, have been in the minority at some point in our

lives. As a teacher in Sierra Leone in the late 1960s I learned what it

means to stand out in a crowd, but I also knew that my time in Africa

was limited and that this was an interlude in my life rather than a

state of being. Female scientists and engineers do not have the luxury

of going home, at least in a professional context.

Social psychologists have documented the disparate experience of men

and women in male-dominated disciplines, particularly in those fields

where there is a cultural assumption that women are less able. This can

lead to “stereotype threat,” a phenomenon originally identified by

Professor Claude Steele of Stanford and his colleagues in which targets

of stereotypes perform less well when they are reminded of the

possibility that their performance may confirm a negative stereotype

about a group to which they belong. For example, psychologists Michael

Inzlicht and Talia Ben-Zeev looked at the mathematical performance of

male and female undergraduates in mixed and single-sex groups. They

found that women performed more poorly in the presence of men than they

did when men were absent and that this deficit actually grew as the

number of men increased. Men, in contrast, were unaffected by the

number of women in the room. Unfortunately, the women most likely to

suffer in such circumstances are those with the greatest ability,

precisely because they are so intent on disproving the negative

stereotype. This may help to explain the fact that the gap between male

and female scores on the math SAT is largest in the most gifted

population.

Just in case you think that negative stereotypes are beginning to

recede from view, consider this exchange between a Rhodes Scholar in

mathematics, studying at Oxford University, and the Queen of England:

The Queen turned to me and said “And what about you?” “I’m from California and I’m studying pure math,” I said. The Queen made a little face that was trying to be friendly and uncritical, but showed playful disgust – at least I think that was it. “Ah…pure maths,” she said. “What are you going to do with it?” “I’m going to become a mathematician. I’d like to go into academia and be a professor.” She paused, looked at me, and then looked away, and said, “Not many girls have the head for…” and paused, wiggling her fingers up by her head, “pure maths.” Looking at her, amazed that the Queen of England thought not only that many girls do not do math, but that many girls cannot do math, I said “Well, actually, I think that most women are told that they can’t do math, and then they don’t.” “Ah…” she said, taking a step backward. Looking at me again, she moved on down the line.

The problem with the numbers game, of course, is that it poses a

chicken and egg dilemma. It will not be possible to erase stereotype

threat until we enhance the number of women in science and engineering,

which we cannot easily do because of stereotype threat. While

strategies to combat this vary widely – from exposing the dangers of

stereotype threat to those at risk, thereby blunting its effects, to

positive reinforcement through mentoring, to single-sex instruction –

all should affirm the innate abilities of women while challenging them

– indeed, expecting them – to exceed their present level of achievement.

I attribute my own resistance to the stereotypical view that women are

not meant to do science to four things: an extraordinary father who

taught me that I could do anything I wanted, and “don’t let anybody

tell you differently,” highly supportive mentors who happened to have

been men, strong and inspirational senior women colleagues at the right

times, and an absolute inability to recognize reality. Let me amplify

the last point, which may be the least obvious. It has been my

experience that many successful women in science simply fail to

perceive that there are obstacles in their path. They are able to go

through life with metaphorical blinders on – not that they would deny

that there are forces working against the progress of women, but rather

that they refuse to acknowledge that those forces apply to them. A

blunt way to describe such women is to say that they refuse to allow

themselves to become victims. They are able to deflect any slings and

arrows that come their way. I do think that this is a tremendous

survival tool, but one that takes the kind of self-confidence that only

comes from strong parents and mentors. As mentors and as parents, we

should be encouraging this trait in young women, rather than engaging

in a lot of hand-wringing about how tough things are.

The importance of good mentors cannot be over-estimated. In the fall of

2001, I appointed a task force to examine the status of female faculty

in the natural sciences and engineering at Princeton University. The

task force found overwhelming support for mentoring on the part of male

and female faculty alike, but among untenured professors, only 33

percent of women, versus 64 percent of men, reported having had this

critical support. Other institutions face similar challenges. In a

fascinating survey conducted by Cathy Trower and Jared Bleak in 2002,

involving almost a thousand male and female tenure-track faculty at six

research universities, women were “significantly less satisfied” than

men in terms of 19 of 28 measures of workplace satisfaction, including

the perceived commitment of departmental chairs and senior faculty to

their success. In no areas were men found to be significantly less

satisfied than women.

It is a fair question to ask why women report a greater level of

dissatisfaction and a greater need for mentoring than men. One view is

that these are signs of weakness on the part of women, signs that they

need more nurturing than their tougher male colleagues. I would argue

that young women’s dissatisfaction and call for mentoring grow out of

their need to have the cultural milieu of science – a culture that was

formed when all scientists were men – interpreted for them. To give you

one example of what I mean – I attended a Gordon Conference in the

early 1980s when my children were quite small. After the evening

session a group of us were sitting around, drinking beer and talking

about our lives. The men were comparing their travel schedules,

bragging about how long they had been on the road and how long it had

been since they had seen their families. Longer, in this case, was

better. I was having precisely the opposite reaction – fretting about

being away for a few days. Imagine the impact of that discussion on the

female graduate students and postdocs at the table.

Let me give you another example where the culture – and the image of

the stereotypical scientist – works against women. Several years later

I was an organizer of a Gordon Conference. With my male co-chair, we

put together a list of 45 speakers, a third of whom were women. We did

not purposely think about gender, we just talked through names. The

next year, that same co-chair organized the same conference – on the

same topics – with a male co-chair, and when their list was published,

43 of 45 speakers were men. What had happened in just one year? The

difference is that when I close my eyes and think “stellar scientist,”

I can imagine a woman in my head. When my colleagues closed their eyes,

they only saw a man. This is not evil, it is human nature. In so many

circumstances we have to fight against the natural instinct to

associate with people who look and think most like ourselves. This

tendency is exacerbated by the fact that the world works by lists,

whether they are lists of individuals to hire, individuals to give

prominent lectures, individuals to nominate for prizes, or individuals

to appoint to important committees, and if women are not involved in

making up the lists, it is almost inevitable that they will be

overlooked.

I have taken a lot of criticism at Princeton for appointing women to

positions of influence in the university. I have argued – sometimes

successfully – that I did not do this deliberately or with a political

agenda in mind. When challenged to explain why other universities have

not hired as many women, my answer is always the same – that I have a

huge advantage, for when I close my eyes I can imagine that a female

candidate could actually be the best person for the position. Thus I

have a larger pool to choose from.

The lesson that follows from these stories is – in the immortal words

of Linda Loman – “Attention must be paid.” For the foreseeable future,

we will have to be eternally vigilant to the ways in which the societal

image of what constitutes a successful scientist or engineer is working

against the goal of increasing women’s participation in these fields.

The Linda Loman rule would argue that departments must be reminded by

deans to look harder for female candidates for admission to graduate

school and, most importantly, when hiring faculty. Deans must be

prepared to turn back searches that have not considered any female

candidates or have constructed the search in such a way that finding a

woman is unlikely. I am not suggesting that a different standard be

applied – I am perfectly confident that women scientists and engineers

compete effectively when given the chance. Because chairs of

departments are so critical in this regard, the choices deans make when

filling these positions are also very important.

Finally, it has been my experience over many years that the greatest

impediment to hiring a woman today is the two-body problem.

Universities that are prepared to be flexible and creative, and willing

to put some elbow grease into helping with spousal employment, are

going to do better over time. I can tell you that the single most

effective thing we did at Princeton to increase the number of women

faculty in the last three years was to appoint Professor Joan Girgus,

the former chair of Psychology, as a special assistant to the Dean of

the Faculty. About half her time is taken up with helping spouses find

employment.

It is clearly not sufficient to improve hiring practices. The same

vigilance needs to be applied to issues of equity once women are on the

faculty. That universities had been unconsciously treating male and

female faculty differently became clear when the then President of MIT,

Chuck Vest, a man of extraordinary character and courage, responded to

Professor Nancy Hopkins’ request for an investigation into conditions

for women faculty at MIT. What we all learned from their experience is

that the Linda Loman rule needs to be applied on a regular basis to

everything from salaries, to space, to resource allocation, to

committee assignments. I believe we owe President Vest and Professor

Hopkins a huge debt of gratitude for raising the issue and then

addressing it in such an open and forthright way. Their example spurred

many other institutions to make positive changes as well.

There is another – and profound – way in which women and men experience

careers in science and engineering differently, and that is not inside,

but outside the laboratory. Let me give you some statistics to make

this point. Over one-third of women scientists and engineers are

unmarried, compared to 17% of men. Ten percent of married women

scientists and engineers have an unemployed spouse compared to 40% of

men. In a survey conducted by the Amercian Chemical Society, 21% of

female chemists identified balancing family and work as their greatest

career obstacle, compared to 2.8% of men. These differences may help to

explain a very worrisome trend. In my own field of life sciences women

now constitute 50% of the bachelor’s degrees awarded and are closing in

on 50% of the Ph.D.s. Yet when my department and those at comparable

universities advertise an assistant professorship, the applicant pool

is composed of only 25% women. The same phenomenon is occurring in

chemistry as well – a field that has made tremendous progress in recent

years in attracting stellar women to graduate training. We have lost

half the Ph.D. pool between the awarding of the doctorate and the first

job application.

The underlying causes for this precipitous drop must be better

understood if we are to make further progress in bringing more women

into the academy in science, mathematics, and engineering. However, it

does not take much imagination to recognize that the drop coincides

with prime child-bearing years. Princeton’s task force on women faculty

in the natural sciences and engineering reported that “There is a

widespread sentiment among men and women, from junior faculty to

department chairs, that it is very difficult for women to succeed

professionally and to have children.” Indeed, as our task force also

noted, “In discussions with both department chairs and individual male

faculty, we were disturbed that several stated that childcare is not

compatible with success in the Natural Sciences and Engineering.”

I thought about naming this talk “Perception vs. Reality” because there

is both truth and fiction in these views. It is more difficult to have

a career as a woman and raise a family; there is no point denying this.

Some sacrifices are unavoidable, for no one, least of all mothers, can

do everything and have everything. There are books that will remain

unread, creative and athletic outlets that will never be pursued, and

friendships that will suffer. And there will always, always be late

nights and early mornings.

My most inventive coping mechanism as a young mother (actually, I was

quite an old mother, if the truth be told) involved my love of the

Sunday edition of The New York Times. In my desperation for a tranquil

moment to read this paper, I used to place my children – who are two

years apart – in the car and drive aimlessly until the motion put them

to sleep. As soon as they were both asleep I would stop – no matter

where we were – and read the Week in Review. I often wonder what people

thought of me as I huddled in my car, frantically trying to get through

the next section before my children woke up.

There are data that measure the challenge women face in combining

science and small children. According to a study published in 2002 and

entitled “Do Babies Matter?” Mary Ann Mason and Marc Goulden found that

“in the sciences and engineering . . . men who have early babies are

strikingly more successful in earning tenure than women who have early

babies.” In the context of their research, “early babies” are defined

as infants who are born within five years of a parent’s completion of a

Ph.D.” This disparity, of course, is precisely what you would expect in

a work environment that was not designed for women with children, and

one that has done little to accommodate the dramatic expansion of women

in the workforce of the last 40 years. The feminist revolution of the

1960s and 1970s that opened so many doors for me proclaimed that women

could and should find fulfillment in work, but there is a wildcard in

this scenario that both complicates and enriches life. The wildcard is

children, whose lives must be advanced as single-mindedly and carefully

as our own.

The other wildcard has been the increased national preoccupation with

work and the demand for instant results that long hours breed – hours

that significantly exceed those of nations such as Germany, France, and

Italy. Although the average workweek in this country has remained

relatively constant since 1970, many Americans are working longer

hours. Between 1970 and 2000, to cite a study by Jerry Jacobs, the

proportion of men working fifty or more hours per week rose from 21 to

26.5%, and the number of women from 5.2 to 11.3%. The growth of

two-income households has also increased the intensity of the workweek

for many Americans. And then there is the rise of single-parent

households, typically headed by a woman. Women without partners now

head more than one fifth of our nation’s families, more than double the

percentage in 1970. Needless to say, the pressure of the workplace on

such families is enormous. And, to top it off, all of these shifts have

occurred against a backdrop of technological changes that have

compressed both time and space, making it easier to feel you are at

work even when you are at home.

I firmly believe that universities can change their practices and

policies to make it easier for women to balance the demands of family

and work. And I do not mean to suggest that universities are unique in

this respect – achieving a balance between work and family is

fundamental to every workplace that hopes to include women. The first

step, to paraphrase the political strategist James Carville, is to

recognize “It’s daycare, stupid!” – daycare that is both accessible and

affordable. When our task force asked what Princeton University could

do to improve the environment for its current and future female

faculty, the second most frequent response, after hiring more women,

was to improve the state of childcare. This recommendation was also

advanced by another task force – one that focused on the health and

wellbeing of our university community. It concluded that childcare was

the highest priority of faculty and staff. Quality childcare that is

close to the workplace, responsive to the constraints of workday

schedules and emergencies, and within the reach of a family’s budget is

tangible evidence and a powerful symbol that an institution understands

the complex lives of its students, faculty, and staff. In response to

another recommendation of the health and wellbeing task force, we are

hiring an individual who will focus on work/family balance issues for

everyone at Princeton.

We have also offered one-year tenure extensions for each child and

workload relief to new parents – male and female – but we discovered

that men tended to take advantage of the tenure extension more often

than women, who were afraid that requesting the extra year would be

interpreted as a sign of weakness or lack of confidence. To overcome

this problem we have just changed the policy so that the extension is

granted automatically. This will not preclude someone from requesting

to come up early for review, but it will mean that the extension will

have no value judgment attached to it.

The tenure review process itself needs to be carefully monitored to

ensure that it is truly rewarding excellence. We need to be wary of the

numbers game – so many articles, so many citations, so many dollars –

and weigh the true quality of the work produced by our faculty, male

and female alike. What advances human knowledge? It is not the bulk of

scholarship that crowds the shelves of our libraries or fills our

electronic journals, but the seminal books and papers that break new

ground and take us to a wholly new level of understanding. There is a

natural desire to quantify our output, but this should not be the

measure of scholarship.

Balancing family and work has never been easy, and it never will be.

Much depends on the creativity and determination of individual parents.

But as seats of learning, universities have both a capacity and a duty

to shape our national discourse on this subject. By creating conditions

where family and work can be balanced, we can serve as a model for

other institutions and enterprises, a model that just might be

contagious.

I prefaced my discussion of the obstacles that female scientists and

engineers confront with the caution that there are no silver bullets.

On the other hand, initiatives such as yours will lead to attitudinal

and organizational changes that will one day complete the process that

has carried women, who could not even vote in federal elections when my

mother was born, into the mainstream of professional life. Let me close

with the faces on the next slide – young women who are among the next

generation of scientific leaders. They, and the thousands of other

young women like them, are a source of inspiration for me, and I hope

for your ADVANCE program, I wish you every success in this exciting new

program.