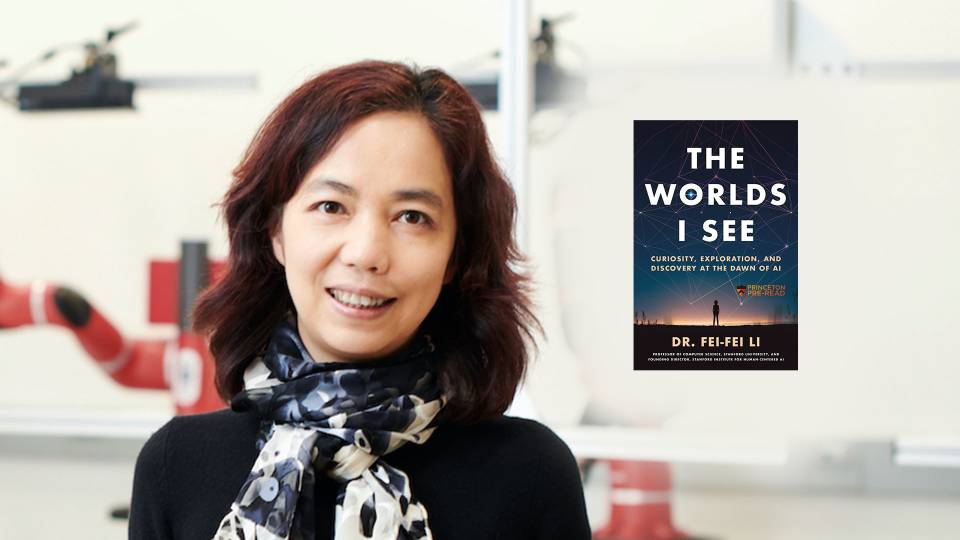

Princeton University President Christopher L. Eisgruber and Fei-Fei Li, Class of 1999 alumna and renowned AI visionary

As the first generation of “AI natives,” today's college students will help set the course for how artificial intelligence affects humanity, the visionary computer scientist Fei-Fei Li told incoming Princeton transfer students and members of the Class of 2028 at Princeton’s Pre-read Assembly Sunday at Jadwin Gymnasium.

“Your generation, the AI native generation, will have to face these questions," she said. "Some of you will become the actual developers of AI. Some of you will become the users of AI. Some of you will become the policy makers of AI. No matter what, your generation needs to figure out what are we going to do with this powerful technology.”

Li, the author of this year’s Pre-read book, “The Worlds I See: Curiosity, Exploration, and Discovery at the Dawn of AI," is a Princeton alumna from the Class of 1999. She immigrated to the U.S. from China during high school and flourished as an undergraduate at Princeton while also helping run her family’s dry-cleaning business in Parsippany, New Jersey.

Li was named last year to the Time 100 list of the most influential people in artificial intelligence and is a leading force for human-centered AI. This spring, she was the 2024 recipient of the University's Woodrow Wilson Award, a prize that celebrates Princeton's mission of service.

She spoke in conversation with President Christopher L. Eisgruber, who selects a different Pre-read book each year to introduce incoming students to the intellectual life of the University. Topics have included freedom of speech, support for first-generation college students, and how to live a meaningful life. The students received a special Princeton Pre-read edition of "The Worlds I See" over the summer.

‘Discovery at the dawn of AI’

After graduating from Princeton, Li completed a Ph.D. in electrical engineering from Caltech. She joined Princeton’s computer science faculty in 2007, and in 2009 she moved to Stanford University, where she is now the Sequoia Capital Professor in Computer Science and a founding codirector of the Stanford Institute for Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence.

While she was a member of Princeton’s faculty, Li began the project that would go on to become ImageNet, the groundbreaking online database that proved instrumental in training computers how to see, which is widely considered the dawn of modern artificial intelligence. Princeton computer scientists Jia Deng, Kai Li and Olga Russakovsky are also members of the ImageNet senior research team.

“Your work, in many ways, laid the foundation for this revolution in artificial intelligence that we are now living with,” Eisgruber said during their conversation. “Say a little bit about what you think AI can do well, what it can’t do at all, and what we should be worried about.”

“AI is progressing at astonishing speed,” Li said. “Anywhere there’s a chip, including a light bulb or a car or your refrigerator — or even a big robot one day — anywhere there’s a chip, there’s computing. Anywhere there’s computing, it’ll be changed by AI.”

She continued: “So from that point of view, AI is already impacting every part of our life.”

Li called AI technology “the biggest superpowered tool that the world of scientific discovery has seen in the past century,” comparing it to the microscope and the telescope in terms of its impact. The key, she said, is building the framework of norms and regulations that shape tool use for the good of humanity.

She offered an example of how these guardrails work. “Today, every single car company has the ability to create a killer car,” Li said. “Just alter a chip in a modern car to say, ‘Every 10 miles, the brakes won’t work.’

“But it doesn’t happen. Why? Because human society has a civic contract with each other. It has laws, it has industry norms. It has regulatory measures [to ensure] that we are using tools responsibly. …That’s where AI is heading.”

A liberal arts perspective

Li urged students to make the most of their time at Princeton. “This is a magical moment of your life. Soak it in,” she said. “Princeton is a buffet of intellectual possibilities and opportunities.”

In her book, she describes how the ideas that led to her role in the AI revolution drew from her strong grounding in the liberal arts. When thinking about computer vision, she started with the link between human vision and human intelligence. She realized that humans are deluged in visual information from birth, and that children learn how to sort everything they see into categories — animal, plant, person, food, and so on. She and her team set about categorizing millions of photographs to train computers in how to interpret visual data.

“That is a liberal arts idea, but it is being pursued by a computer scientist trying to understand how we make technology that functions in our world,” Eisgruber said.

Li said the human-centric approach to AI that she has developed is profoundly informed by the humanities. In answer to a student’s question, Li talked about her research with “ambient intelligence” in healthcare, using AI monitoring to extend nurses’ and doctors’ awareness of patient needs.

“A lot of my applied research is in healthcare, and my life also has a lot of intimate understanding with healthcare system because of taking care of my mom,” she said. “I firmly believe AI can be a very powerful tool for healthcare delivery and medicine in general, but this is an industry whose mission, at bottom, is humans taking care of humans. There are places where no machine can go: when a human needs a human, whether it's a loved one or a professional one or a team, or a combination. And I think that's how we know that AI will never replace our humanity.”

Balancing work, study, family

When Eisgruber opened the floor to student questions, the newest Princetonians made long lines behind each of the six microphone stands. The first question, on juggling personal and academic commitments, struck a chord with Li, who writes in “The Worlds I See” about shuttling back and forth between her life as a Princeton student and her weekends working at her family’s dry-cleaning business.

She talked about finding mentors — and discovering that many of her fellow students and her professors were eager to support her.

“Believing that there are people who are willing to help you really did help me a lot,” she said. “And once I experienced that, it gave me a sense of gratitude that created a positive reinforcement cycle that encouraged me to seek more help when I need it.”

“I love that she mentioned the struggles of being an immigrant studying at Princeton,” said transfer student Amelia Melendez. “As a first-generation student, I completely understand how hard it is to balance studying, working and helping your family to thrive at the same time. And as a woman in STEM, I was relieved when she said that she found a lot of support from her male professors at Princeton.”

After the session ended, Li was thronged by eager students asking for selfies and for Li to sign copies of “The Worlds I See.” Several students told her they saw themselves in her journey: some as an immigrant, or as someone economically fragile still supporting their family, or as an interdisciplinary thinker.

The conversation between Li, Eisgruber and the Class of 2028 will continue over the fall during smaller roundtable discussions in the residential colleges.