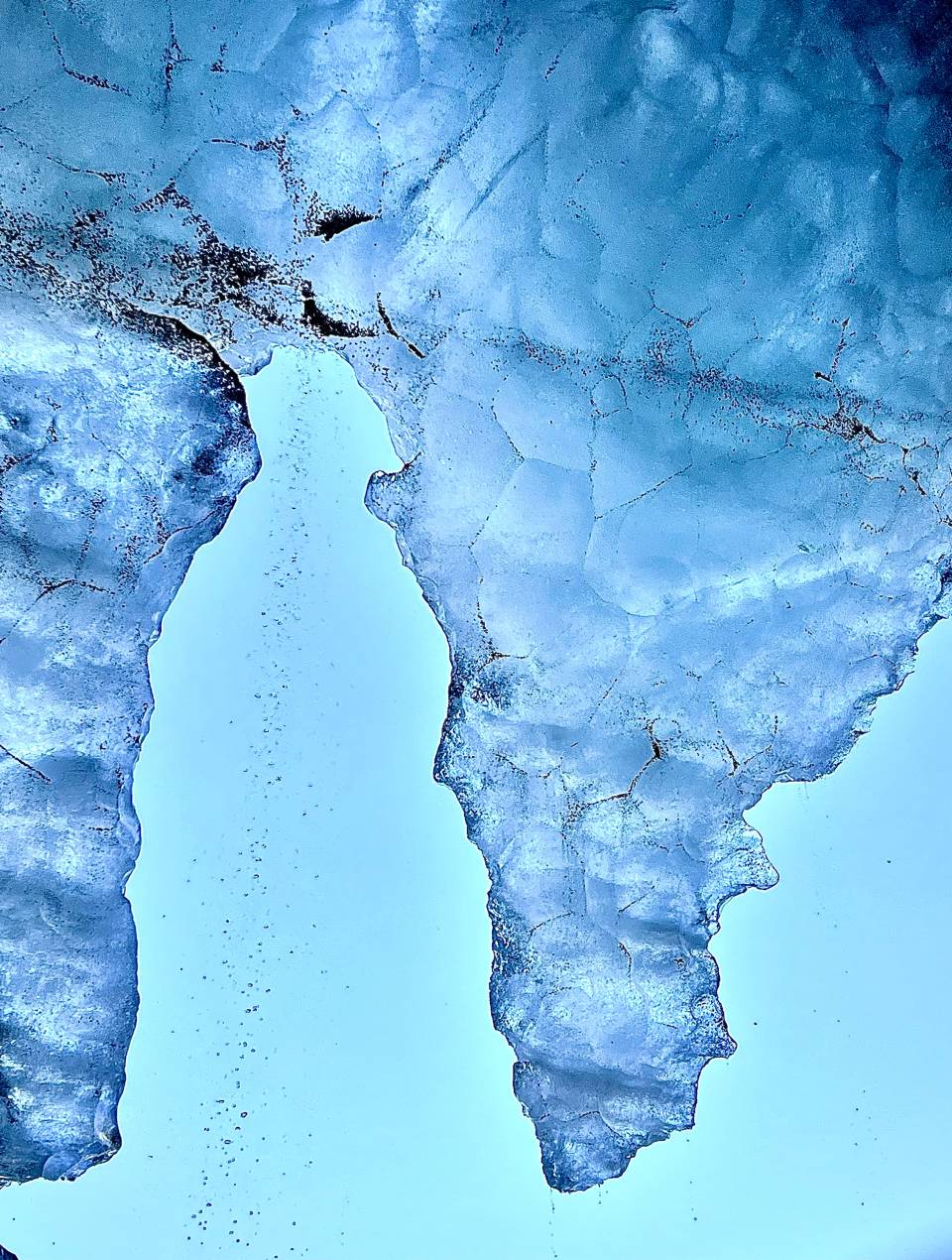

At the northern and southern tips of our planet are tiny bubbles of air trapped for millions of years within polar ice. These microscopic time capsules hold a record of Earth’s atmosphere — and thus its climate history.

“Ice is time, crystalized,” said Princeton environmentalist Anne McClintock. “Ice is the custodian of deep time, sealing the past in its frozen crypts. Ice remembers.”

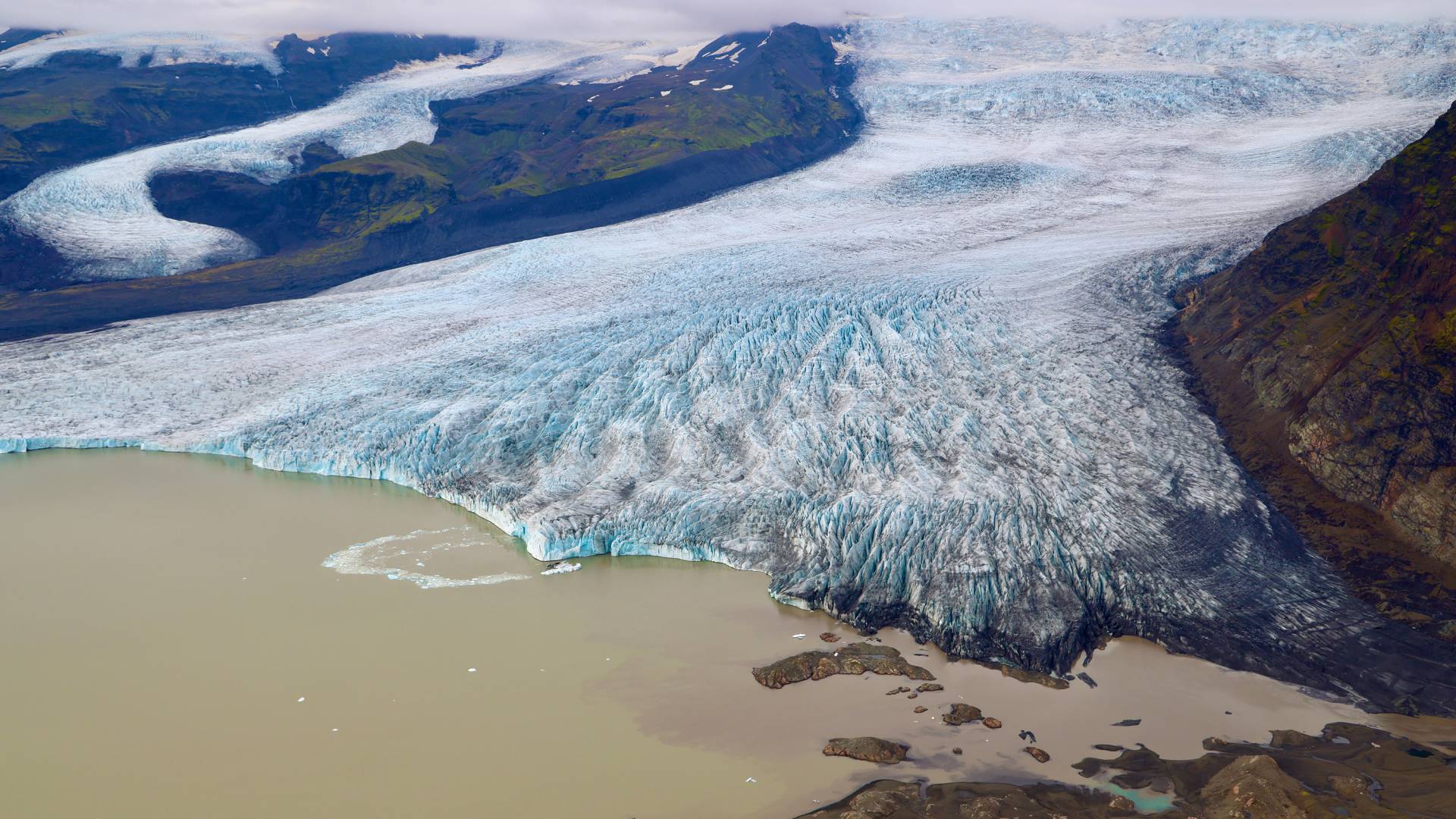

It also looks ahead. The melting glaciers that McClintock studies in Iceland portend a future of rising sea levels and communities displaced from their homes if climate change persists.

We talked to three Princeton researchers who travel to the polar regions for their research to capture data, images and narratives that can help turn back the tide.

John Higgins: Hunting for ancient air

“Three and a half million years ago, Earth’s climate was warmer than today’s by about 2 degrees — just what we’re worried about in the next half century," said climate scientist John Higgins, an associate professor of geosciences at Princeton. “If we want to understand the future, we should be able to understand why Earth’s climate has changed in the past.”

Princeton researchers set up camp on the blue ice of the Allan Hills in Antarctica, where they collect ice cores containing ancient air.

Higgins calls ice cores collected from the Earth’s polar regions “the gold standard for climate history.”

“To reconstruct past environments, you can’t ask for anything better than a sample of ancient air or a sample of ancient water,” he said, "and ice cores have both.”

Over the course of his career, Higgins has repeatedly set and then broken world records for ancient ice. Most recently, his postdoctoral researcher Sarah Shackleton — a distant cousin of legendary Antarctic explorer Ernest Shackleton — announced at the annual meeting of American Geophysical Union in December that their team had found 4-million-year-old ice in the blue ice region near Antarctica’s Allan Hills. For context, 4 million years ago our hominid ancestors were just considering coming down from trees, and megalodons still terrorized the oceans.

Climate scientists value these sediment-free blue ice cores because they contain trapped air bubbles. The Princeton team measures the ice’s age by dating the ancient air samples directly, using a technique pioneered by Michael Bender, an emeritus professor of geosciences.

“What we are really hunting for is old air, to measure greenhouse gas levels,” said Higgins.

Since thermometer measurements only go back a century or two, climate modelers depend on the air, water and trace chemicals preserved in ice and fossils to understand climate change over the eons and anticipate the future. “If you want to ask the questions for what the climate will be like in 50 or 100 years, you have to go outside the bounds of instrumental records, and that’s where Earth history comes in,” said Higgins.

Where it is too cold for snow to melt, that snow and air will be compressed into ice by subsequent years’ snowpack, so the oldest ice is usually found at the bottom of a very tall stack of ice. Drilling ever-deeper ice cores has resulted in a continuous climate record, but it has failed to find any ice more than about 800,000 years old.

Higgins’ team takes a different approach for their record-breaking ancient ice cores, drilling shallow cores from ice that has been pushed up from great depths by geologic processes. Their samples don’t make a continuous record, but instead provide snapshots of older eras that researchers can then build into their climate models.

Justine Holzman: Sea ice as a sentinel for the here and now

"Sea Ice Daily Drawings," Justine Holzman and Cy Keener, 2022

Much of what is known about Arctic ice comes from sensors deployed by researchers. Since 1979, the International Arctic Buoy Programme has published data from these sensors, which has been integral for environmental forecasting.

For the last four years, Justine Holzman, a landscape researcher and a second-year graduate student in history of science at Princeton, has contributed to this effort, not only helping to design and build critical sensors, but also working with a team to create visual art based on the data collected.

Holzman and her collaborators — artist Cy Keener, climatologist Ignatius Rigor and scientist John Woods — have integrated field data, remote satellite imagery, scientific analysis and multimedia visual representation as a way to document disappearing sea ice and icebergs in the Arctic.

“What has been striking about working in this context is that the dynamics and behavior of sea ice already have been dramatically impacted by climate change,” she said. “Connecting to this landscape with our environmental sensors over the past few years has been a visceral experience of the current effects of climate change — it is truly now in the Arctic. If we think of the sea ice and icebergs as changing on a daily basis, having a lifespan, then we might approach climate issues differently.”

The group’s scientific and creative work was on display earlier this year at the National Academy of Sciences in Washington, D.C., including two series of artworks representing different geographies and types of ice.

Their “Sea Ice Daily Drawing Series” was produced from field data collected in the Arctic, accessed from Utqiagvik, Alaska. The “Iceberg Portraiture Series” originates from an iceberg tagging expedition in Disko Bay, off the coast of Greenland.

Holzman said the works emphasize the visual and spatial aspects of the collected data. The sea ice drawings use a one-to-one scale so they can be viewed relative to the actual size of the sea ice. The iceberg portraits are drawn at the same scale so they can be compared to one another. “We hope that what emerges is a different reading, one that is experiential and perhaps provides another entry point into these physical landscapes and their respective datasets,” she said.

Students participating in a GradFUTURES learning cohort from Princeton’s Graduate School, as well as some D.C.-area alumni, gathered in January for a tour of the exhibit, titled “Arctic Ice: A Visual Archive.”

“It was wonderful to share my work in the gallery with Princeton graduate students and alumni, and to feel supported by my Princeton community,” Holzman said.

Her group’s work continues. They are headed to the Arctic again this spring to deploy another round of buoys. Holzman said she will use that new data to continue expanding each art series and depicting their findings.

“I am looking for more opportunities to share this work with the public and to continue having the interdisciplinary discussions we had at the National Academy of Sciences.”

Anne McClintock: ‘Unquiet Ghosts’ and the future

There was a moment last August when Anne McClintock stood upon a frozen ledge inside of a volcanic cave in Iceland that caused her to make an immediate, visceral connection to her research into the disappearing coast of southern Louisiana.

“Through the solid ice was this roaring torrent, going so fast, and just this deafening noise,” said McClintock, the A. Barton Hepburn Professor of Gender and Sexuality Studies and the High Meadows Environmental Institute.

It was the sound of glacial ice melting in real time. That thundering rush reminded her of another experience she’d had, years earlier, driving on an island along the Gulf of Mexico while researching the islanders who have been called the first federally funded climate refugees in the U.S. Seemingly out of nowhere, her vehicle was overcome by waves crashing over the road, leaving her stranded until the water subsided.

It’s a long way from southern Louisiana to Iceland — on the order of 6,000 miles — but the two are more intimately connected than most people would imagine.

Southern Louisiana is the fastest disappearing land mass on Earth. Meanwhile, Iceland is recording the fastest melting glaciers, which are compounding land loss and rising oceans in Louisiana and elsewhere.

McClintock has been exploring these connections and their links to human activity to tell a far larger and more urgent story about climate change.

Her forthcoming book, “Unquiet Ghosts, From the Forever War to Climate Chaos” (Duke University Trade Series), uses writing and photography to braid together the acute crises of melting ice caps, rising oceans, mass displacements of people and global militarization.

For years, McClintock has been documenting the plight of the Indigenous community on Isle de Jean Charles in Louisiana, whose land (once the size of Manhattan) has been reduced to an island two miles long and a quarter-mile wide. She also had done extensive research on the global environmental impact of militarization, one of the greatest contributors to greenhouse gas production and climate change.

Her documentation of glacial breakdown in Iceland is both an outgrowth of that work and also in line with her original intent, which was to make climate change “tangible, visible, audible, palpable and imaginable to people.”

She traveled to Iceland to explore and capture the melting ice in much the same way she has gathered stories and images of the disappearance of land in Louisiana. In the case of glaciers, however, that loss is perhaps more urgent and dire for the planet’s future.

In addition to serving as a geological record of the Earth, the ice keeps the planet cool and reflects the sun’s rays, offering a double defense against climate change. Its melt not only causes sea level rise and diminishes protection from the sun, but also creates unprecedented change in polar regions.

The loss of permafrost threatens human and animal life in these regions where the ground is no longer stable. The thawed permafrost also could speed up climate change as stored carbon that was once frozen in the ground is released into the atmosphere.

As McClintock stood near the terminus of one glacier, which is known as the snout, she knew from her conversations with locals that it had once extended much farther toward the ocean. “It’s very hard for our imaginations to wrap around that,” she said. “I think that’s where storytelling comes in. We have to try to convey the melting of these glaciers in other forms.” Because, as McClintock said: “The future is now.”

Support for these projects came from the National Science Foundation, the Simons Foundation, the MacArthur Foundation, the International Arctic Buoy Programme, the Office of Naval Research and the High Meadows Environmental Institute's Walbridge Fund.