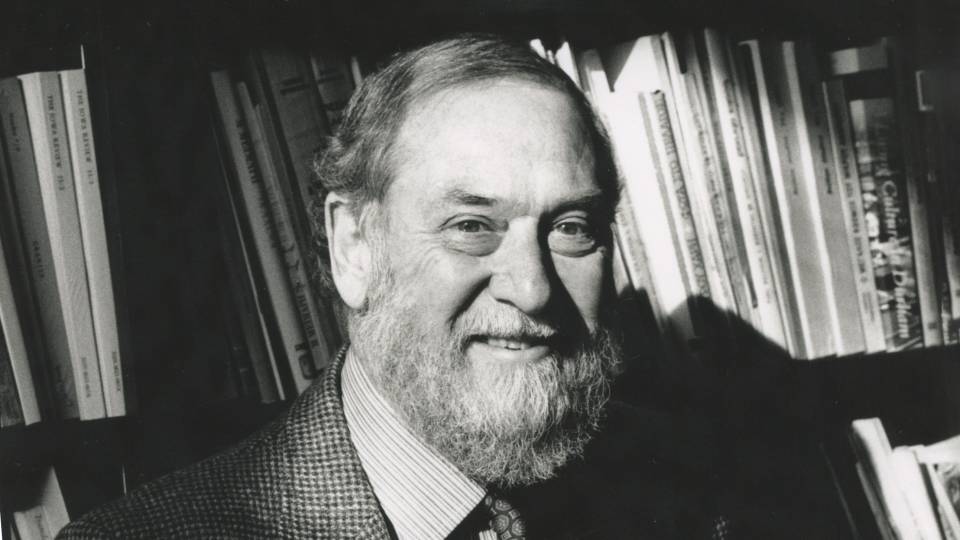

Russell Banks, award-winning novelist and the Howard G.B. Clark ’21 University Professor in the Humanities, Emeritus, and professor of the Humanities Council and creative writing, emeritus, died Jan. 8 from cancer at his home in Saratoga Springs, New York. He was 82.

Russell Banks

Banks joined Princeton University in 1982 and transferred to emeritus status in 1998. He was a pivotal member of the creative writing program and helped shape the continued growth and excellence of the program, prior to the establishment of the Lewis Center for the Arts, alongside distinguished colleagues including Toni Morrison, Joyce Carol Oates, James Richardson, Paul Muldoon and Edmund White.

“There was a sense even then that Russell had not only the ambition but the ability to take on some of the most charged subjects in American life, notably race and the class divide that remains largely unacknowledged to this day,” said Paul Muldoon, the Howard G.B. Clark ’21 University Professor in the Humanities and professor of creative writing in the Lewis Center for the Arts, who directed the creative writing program from 1993 to 2002.

And yet, “however serious he was as an artist, Russell always had a smile on his lips and a twinkle in his eye,” Muldoon said. “He clearly adored his students and they clearly adored him.”

He continued: “The combination of Russell Banks, Toni Morrison and Joyce Carol Oates as the main teachers of prose fiction through the 1990s helped establish the creative writing program’s reputation as second to none.”

Joyce Carol Oates, the Roger S. Berlind ’52 Professor of the Humanities, recalls sitting in her office across the hall from Banks in the late 1990s, each of them working on a long novel — Banks on “Cloudsplitter” and she on “Blonde” — “complaining to each other of how difficult the writing was (since no one else wanted to hear).”

Oates said a favorite memory of their years-long friendship took place in March 1989, when they gave a reading together for Princeton students — along with Toni Morrison and several other creative writing faculty members — of Salman Rushdie’s “The Satanic Verses,” who was under death threats at the time, to show their support of free speech.

“Russell was a moral compass for many, in the tradition of such writers as Melville, Hawthorne and Conrad, for whom the moral ambiguities of life are of fundamental concern; but an early, abiding influence was Nelson Algren whom Russell had met as a young man and much admired for his stark, gritty, unflinching urban realism,” said Oates, who has taught at the University for 44 years.

“The only signs of Russell Banks’ working-class origins were an earring and a beard. And maybe his generosity of spirit,” said Edmund White, professor of creative writing in the Lewis Center for the Arts, emeritus.”

The eldest of four children, Banks was born on March 28, 1940, in Newton, Massachusetts, to Earl Banks, a plumber, and Florence Banks, a homemaker and bookkeeper. He was raised in Barnstead, New Hampshire, and Wakefield, Massachusetts. The first in his family to go to college, he attended Colgate University on a full scholarship but left during his first year to work for five years, before completing his bachelor’s degree at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill in 1967. In 1989, he married the poet Chase Twichell, who taught poetry at Princeton from 1990 to 2000.

His books were populated by working-class Americans — a reflection of his own roots. His first book, an anthology of poems called “Waiting to Freeze,” was published in 1969. His first novel, “Family Life,” was published in 1975, and his first short-story collection, “Searching for Survivors” (1975), received an O. Henry Award. He wrote 21 books, including fiction, short fiction and non-fiction. His novels “Continental Drift” (1985) and “Cloudsplitter” (1998) — his first historical novel, about the abolitionist John Brown — were both finalists for the Pulitzer Prize for fiction. He received the Anisfield-Wolf Award — established in 1939 to recognize books that have made important contributions to our understanding of racism and our appreciation of the rich diversity of human cultures — for “Cloudsplitter.”

Two of his novels, “Affliction” (1989) and “The Sweet Hereafter” (1991), were adapted for the screen; both films were released in 1997 and both were nominated for Academy Awards. His work has been translated into more than 20 languages. His essays and reviews have been published in major magazines, and he has written screenplays and poetry.

“Always warm, funny, gentle and amusing, he was the cloud ten of college teaching,” said John McPhee, a senior fellow in journalism who has taught at the University since 1975.

McPhee, who grew up in Princeton, added, “One of his daughters married the son of one of my high-school-basketball coaches, and that of course created a firm, familial bond between me and Russell.”

In a University news story about Banks on the occasion of his retirement, Banks said his teaching and writing was informed by the belief that “writing is the ultimate social act. . . an attempt to communicate with strangers at the most intimate level.”

“During his time in the creative writing program, Banks was part of the Humanities Council’s lively interdisciplinary community that connects journalists, writers, filmmakers, painters, scholars and others in wide-ranging, provocative conversations,” said Kathleen Crown, executive director of the Humanities Council. She praised his wisdom and generosity in selecting early-career writers as Hodder Fellows for a year of “studious leisure” at Princeton.

“Russell Banks was a kind, generous and compassionate professor and colleague when he was teaching at Princeton, and former colleagues and students have spoken fondly of their memories of him,” said Yiyun Li, professor of creative writing in the Lewis Center for the Arts and director of the Program in Creative Writing.

Many of Banks’ students went on to pursue careers as writers.

“Russell Banks was my creative writing thesis adviser. He was absolutely wonderful,” said Akhil Sharma, who graduated in 1992 and is an essayist, short story writer and the author of several novels, including “An Obedient Father” and “Family Life.” “He was both cheerful and very practical. He was often teasing and playful. ‘We are all workers in the vineyard,’ he would say when talking about a writer whom he did not want to speak ill of.”

Sharma said some of his stories that he worked on with Banks went on to be published in major magazines and win prizes — including “Cosmopolitan.” “When we realized it might be a good story and I was still writing it, Russell said, ‘Now, don’t do anything stupid with it.’” Sharma also wrote “If You Sing Like That For Me” under Banks’ guidance; both stories were published in The Atlantic and then widely anthologized.

Sharma continued: “We think of Russell as primarily a writer, but he was also someone who helped defend writers who were in physical danger.” Banks was instrumental in expanding the Cities of Asylum of Europe — a nonprofit that supports freedom of creative expression and provides residencies to persecuted writers and artists — to the United States. Sharma is a board member of City of Asylum Pittsburgh, in which Banks was especially involved.

Banks received numerous honors and awards including Guggenheim and National Endowment for the Arts Creative Writing fellowships, the Best American Short Story Award, the inaugural Thornton Wilder Prize, the American Book Award, the Literature Award from the American Academy of Arts and Letters, the 2011 Commonwealth Writers’ Prize and the 1985 Dos Passos Award for Literature, among others.

A longtime PEN America member, he was also a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and the American Academy of Letters. He was a past president of the International Parliament of Writers and the official New York State Author from 2004 to 2008. In 2014, he was named an Officier de l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres by the French Minister of Culture.

He is survived by his wife, Chase Twichell; Lea Banks, his daughter from his first marriage; three daughters, Caerthan, Maia and Danis Banks, from his second marriage; his brother, Stephen; his sister, Linda Banks; his half sister, Kathleen Banks-Nutter; two grandchildren; and a great-granddaughter.

View or share comments on a blog(Link is external) intended to honor Banks’ life and legacy.