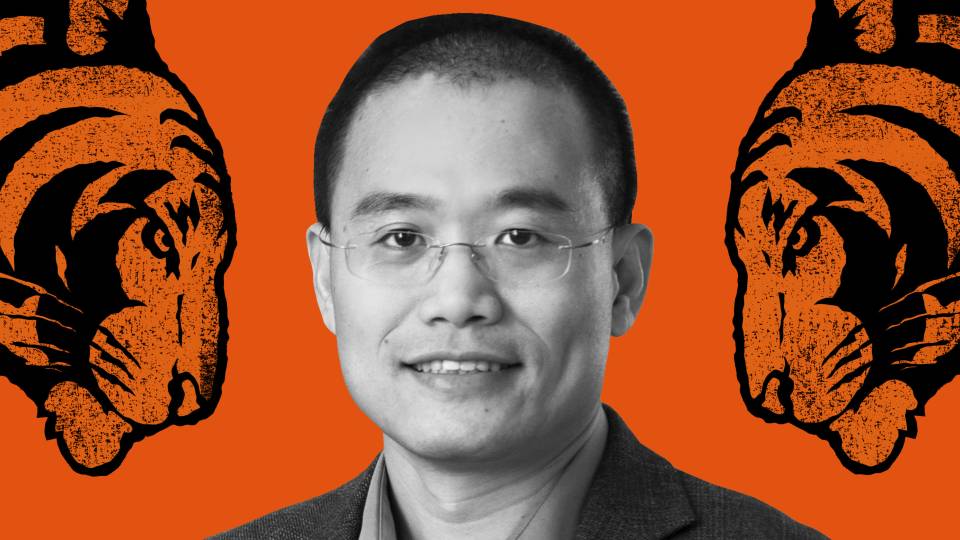

Stephen Kim

Lunar New Year celebrations this month ushered in a Year of the Tiger, a moment of pride as well as reflection for Princeton's vibrant Asian and Asian American community. Throughout the year, we will be elevating the voices of faculty, staff, students, alumni and researchers from the community in a series of thoughtful interviews exploring questions of identity, pride, hope, the lived experience of anti-Asian racism, and meaningful steps that allies can take.

This month, Stephen Kim, associate director for communication and information at the Princeton University Art Museum, begins the series with his thoughts about the urgency, in this particular Year of the Tiger, "to actually confront questions of racism and identity." Read the full series below.

How do you self-identify?

I self-identify as Asian American and as Korean American. How we all identify in 2022, in the Year of the Tiger, is of a lot more interest, curiosity and complexity than it's ever been in my lifetime. If somebody asked me just to identify in a vacuum, I would identify as somebody who is curious, who really enjoys exploring questions of humanity, and esoteric things that I think define me. I've been reluctant during a lot of my life to identify in racial, ethnic terms, in part because I was bullied and racially abused while growing up.

In high school, there was a kid in my class who only referred to me with a racial epithet every single day. He refused to call me by my name, and I have an easy name. I never stood up for myself because I just wanted to fit in, and no student or teacher ever stood up for me. In college, on my very first night on campus, I was with two other Asian students. A car of teenage boys drove by and threw beer bottles at us, shouting, "Ching chong. Go back to China." I wanted to hide my identity as Asian American. I remember looking in the mirror as a kid and wishing I was white, like really, really wanting to be part of the majority.

Stephen Kim

Early in my career, I was a lawyer. Once, I was sitting with a colleague who was Chinese American at a negotiation in a luxurious partner's office in Washington, D.C. In the middle of the negotiation, another lawyer indicated a piece of furniture in the room, and said, "Oh, by the way, I just want to say I'm so glad we have this beautiful Chinese cabinet for Stephen and Brad to enjoy." It was totally random. And this is when I learned not to believe folks when they say, “but I don’t see you as different.”

An Asian American student I know very well went on a recent trip to D.C. with two friends, also Asian Americans. She told me they were racially catcalled at every museum they went to. And that they felt vulnerable because they had forgotten their mace. I said, "What do you mean, you forgot your mace?" She said, "We all carry mace," as if this should be obvious to everyone.

Now, in 2022, though, particularly in light of Black Lives Matter and everything that's happened in the last year, I choose to identify as Asian American because, to me, claiming our whole selves is part of how we protect and bridge our communities.

What makes you proud to be an Asian American?

I wasn’t always proud to be Asian American, but then there was a period where I began to say, "I'm not going to flee from my identity, but how do I embrace it?" I first started to spend time on the Princeton campus in the early '90s when I was dating my wife, a member of the Class of 1992. There was a small Asian American population then and there’s been a lot of evolution on this campus in the last 30 years, in a good way.

I’m proud to be a co-president of Princeton’s Asian American staff ERG (employee resource group). A small cadre of us formed the group completely virtually at the beginning of the pandemic, which exposed a lot of anti-Asian prejudice in our community. In the wake of the George Floyd murder, we also felt like we didn't have an obvious place on campus to either express community or to share experiences. Many Asian Americans are raised in households where you don’t complain and you certainly don’t push back. Many of us felt like, "Wow, there is no place for us." The University, including Michele Minter [vice provost for institutional equity and diversity] and Kimberly Tiedeken [director of diversity and inclusion, Human Resources], was tremendous in supporting this new ERG.

We have a lot of programming, such as conversation spaces. We did a session with Calvin Chin [director of Counseling and Psychological Services] designed around support for community members who might be subject to anti-Asian prejudice. We just did a Lunar New Year program. It's very much about building community at this moment, providing the kind of support for the community that is key in 2022. Most importantly, our members have been able to share their experiences and ideas transparently and vulnerably, building valuable relationships with fellow staff from across our campus. We’ve grown from about 30 members to more than 120.

What can allies and others do to counter anti-Asian racism?

Be aware that other people may have grown up under a different set of circumstances than you. I use that example about the kid in my school who called me a racial epithet to level-set for people, to say, "You think I'm just like you, but I am not." You also can't assume by looking at me that you understand my context — which of course could be said of everyone. Someone might say to me, “I've been to China 15 times,” thinking I will relate to that. Asia is made up of 48 different countries, technically. Even within Asian American, we have South Asians, East Asians, mixed race, adoptees. It's a very diverse group. Don't assume you know what the other person's experiences, orientation or heritage might be.

Think about the challenges of those who identify as Asian American. For many of us, we are immigrants and it's sometimes hard to identify as American because we're continually made to feel like outsiders in the country where we were born. And it's very hard to identify as Asian because we didn't grow up in Asia. Many of us were raised by immigrants, but we don't have a direct relationship with the country where our parents grew up.

Take advantage of the many opportunities on campus to engage actively — to not just talk about diversity, but to actually confront questions of racism and identity. There are so many forums, symposia, public conversations, student plays, and, of course, Art Museum experiences tuned toward that. It's not hard to go to. Most of it's just a click away on Zoom.

Be intentional about self-reflection. Everyone has the analytic capability to be self-reflective, to realize that each of us brings unconscious biases to whatever table we're sitting at. If you're a manager, for example, you're making decisions that are guided by unconscious biases. It's time to recognize those moments and then call yourself out, whatever that means to you.

Acknowledge that racism is everywhere, not just in certain parts of the country. Especially in all the heightened awareness of the last two years, people may think those are prejudices of other people, and are not willing to confront that it's at home and in your own head that these prejudices are born and nurtured unconsciously within communities over time.

Are there examples from what you’re involved in to counter anti-Asian racism that you think would help others?

I'm extremely proud of the work I get to do at the Princeton University Art Museum. We have a globe-spanning collection and an incredibly dedicated team devoted to educating, challenging, and inspiring our campus community (and beyond). Our two current exhibitions are about confronting the challenging complex aspects of identity. I encourage everyone to go see them.

The exhibition at Art@Bainbridge on view through Feb. 27, “Between Heartlands,” by Kelly Wang, a 29-year-old artist born and raised in New York City, is very much influenced by her Asian American identity. She addresses racism and the pandemic. Both her parents got sick in March 2020 with COVID-19, and then her father died of it. Her mother is Chinese. Her father was Caucasian.

In one installation in the Princeton University Art Museum exhibition "Between Heartlands," Asian American artist Kelly Wang has written on traditional Chinese paper racial slurs she heard as a child, tucked into vintage and contemporary compacts, interspersed with traditional Chinese artwork. There’s a double meaning here, a reference to the compact she uses on the subway platform in New York to make sure nobody's behind her. On view through Feb. 27. Collection of the artist.

There is one installation in the exhibition comprised of found vintage and contemporary cosmetic compacts. Tucked into the compacts are phrases Kelly has written on traditional Chinese paper — slurs and attacks that she heard as a child, as young as age 6, such as “We're going to kill all the Chinese people.” But she's also interspersed these with the beauty of the traditional Chinese artwork that she makes as an adult, using both traditional and contemporary techniques. And there’s a double meaning here, a reference to the compact she uses on the subway platform in New York to make sure nobody's behind her about to shove her onto the tracks.

The other current exhibition, “Native America: In Translation,” curated by artist Wendy Red Star, at our new gallery space Art on Hulfish, gathers work by Indigenous artists who consider the complex histories of colonialism, identity and heritage. With both these shows, we are creating programming where people can have conversations with artists and with each other, mediated by objects, about very sensitive topics. That is one of the central functions of a museum. I feel very fortunate that I'm at a job where I can promote these sorts of expressions and programs with the ultimate goal of using extraordinary art to teach and connect our visitors, in the service of humanity.